After all the returns and exchanges, we have five black chore coats ready to ship – four XXLs and one L. They are available here if you hurry.

— Christopher Schwarz

After all the returns and exchanges, we have five black chore coats ready to ship – four XXLs and one L. They are available here if you hurry.

— Christopher Schwarz

Speaking as someone who has read too many woodworking books, there are a few archetypes: the project book (“Birdhouse Bonanza”), the tool book (“Router Rodeo!”) and the black-turtleneck-and-beret books on why me make things (“My Mortise is Deeper than My Soul”).

Nancy Hiller’s new book “English Arts & Crafts Furniture” is none of these books. But you probably knew this because Hiller’s name is on it.

Instead “English Arts & Crafts Furniture” is one of those rare books that rewrites the history of the Arts & Crafts movement (it’s not just a reaction against industrialization – plus slats ‘n’ oak) while making you laugh and occasionally blush. She delves deep into the personalities that shaped the movement – John Ruskin and William Morris, plus the makers Harris Lebus, Ernest Gimson and the Barnsleys. And she presents three projects that are directly tied to her narrative thread.

It’s quite a trick, actually. It turns out that Hiller has written a project book with some very good information on tool use that happens to make me wonder about my motivation for making furniture for sale (now, where did I put my beret?).

Among her other feats of legerdemain: Hiller’s research is impeccable and copiously footnoted, yet the book is a breezy read. Despite the high level of craftsmanship displayed in her project pieces, Hiller manages to slough off her ego by profiling all the people who helped her along the way to make these incredible works – the stained glass maker, the woman who made the rush seats, the guy who make the hardware for her sideboard. And she manages to pack an incredible number of ideas and beautiful images into a book that is just 144 pages long.

If the book has any failings, I’d say that the illustrations could be improved. While there’s enough information to build the projects (and that’s all that matters), the line drawings don’t match the gorgeous photos, layout and typography. The book has some beautiful and expensive touches – the full-color endsheets match the wallpaper on the cover – but I kind of gag when I see advertisements bound into the back of a book. Those, however, are personal problems.

In all, this is a rare woodworking book. The kind of book that makes me jealous that I didn’t write it myself. (Or at least come up with Hiller’s fascinating way of combining biography, history, sociology, workshop instruction and butt jokes.)

So buy it, even if you think you don’t like English Arts & Crafts (though you probably will after seeing the movement through Hiller’s eyes). And buy it because it supports this kind of work that has become rare in the woodworking field. Most woodworking books these days have more gimmicks than gumption.

“English Arts & Crafts Furniture” is available from ShopWoodworking and other retailers. However, Hiller will make more money if you buy it from ShopWoodworking or directly from her at her upcoming book tour.

— Christopher Schwarz

P.S. If you are particularly charmed by the side chair in the book, Hiller will offer additional plans of the chair. Those will be available through her website.

Our warehouse began shipping pre-publication orders for “Welsh Stick Chairs” yesterday and is working on getting the remainder out in the mail today.

I’m going to be a bit of a wiener here and say that I think our edition exceeds the quality of all the previous editions. This had little to do with me and everything to do with our prepress agency, the special printing press we used for this job and the press operators.

In comparing the images among all the editions of “Welsh Stick Chairs” I own, I can find no image degradation in ours. The text is, of course, super crisp because we reset the entire thing using the original fonts and line spacing from the first edition (even replicating a number of typesetting errors in the interest of accuracy).

The biggest manufacturing improvement is that we sewed the signatures in addition to bedding them in adhesive, making for a permanent book.

John Brown’s words are, of course, the same and cannot be improved upon.

Even if you decide to pass on purchasing this book, don’t worry. We’ve made sure our edition will be around for generations to come when you (or your children) decide to pick up a copy.

“Welsh Stick Chairs” is $29, which includes domestic shipping (yes, even to Alaska and Hawaii).

— Christopher Schwarz

All pre-publication orders placed through the Lost Art Press store will receive a pdf download of the book at checkout. After the book ships, the pdf will cost extra.

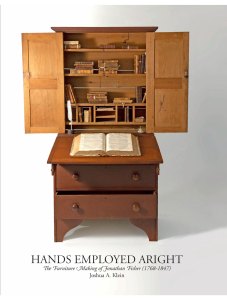

“Hands Employed Aright” is the culmination of five years of research into the life of Jonathan Fisher. Fisher was the first settled minister of the frontier town of Blue Hill, Maine. Harvard-educated and handy with an axe, Fisher spent his adult life building furniture for his community. Fortunately for us, Fisher recorded every aspect of his life as a woodworker and minister on the frontier.

In this book, Klein, the founder of Mortise & Tenon Magazine, examines what might be the most complete record of the life of an early 19th-century American craftsman. Using Fisher’s papers, his tools and the surviving furniture, Klein paints a picture of a man of remarkable mechanical genius, seemingly boundless energy and the deepest devotion. It is a portrait that is at times both familiar and completely alien to a modern reader – and one that will likely change your view of furniture making in the early days of the United States.

This hardbound, full-color book will be produced entirely in the United States using quality materials and manufacturing methods. You can get a sample of the writing, photography and design of the book via this excerpt.

You can place your order for “Hands Employed Aright” here.

— Christopher Schwarz

P.S. As always, we do not know which of our retailers plan to carry this book – it’s their decision; not ours. We hope that all of them will stock it. Contact your nearest retailer for more information.

Joshua Klein’s biography of Jonathan Fisher, “Hands Employed Aright,” needs only a few tweaks today before it goes into production with our prepress agency. With any luck, the finished book should be in our hands in early August.

Even though I’ve edited this book several times, reviewed every photograph and examined every finished page, I am continually struck by how amazing this book is. It is – in short – a window into the daily life of a working hand-tool craftsman on the American frontier in the 19th century.

In many ways, this book answers the question a lot of us ask ourselves: What was it like to run a pre-industrial furniture shop? But instead of answering that question with conjecture or breadcrumbs of evidence from probate inventories and price guides for piecework, Klein answers the question with an absolute fire hose of original material that has been under wraps for almost 200 years.

Jonathan Fisher (1768-1847) documented every aspect of his life in daily diaries written in a code he made up. Many of his tools and finished pieces of work have survived. And once his secret code was broken, the diaries and the archaeological evidence could be put together to paint an incredibly detailed portrait of Fisher and his daily life in the shop.

While that’s interesting, Klein didn’t stop there. He examined Fisher’s tools and furniture in remarkable detail to figure out his working methods. Then he put those methods to use in his shop, reproducing several pieces to determine if his theories were correct.

While this book won’t teach you how to cut dovetails or plane boards, it will definitely make you reconsider your own methods and your view of what craftsmanship really is.

In addition to all this, Fisher provides us with a photographic inventory of Fisher’s tools and finished pieces, much like Charles Hummel’s classic “With Hammer in Hand.”

It has taken five years of hard work by people all over the country to put together “Hands Employed Aright,” and I think you will be pleased with both the content and the way we are making this book. Designer Linda Watts took immense care with the layout and was slowed down by the fact that she kept reading and re-reading the book herself.

We will open up pre-publication ordering in the next couple days. “Hands Employed Aright” will be 288 pages, hardbound, in full color and printed on heavy coated paper. The price will be $57, which will include domestic shipping.

— Christopher Schwarz