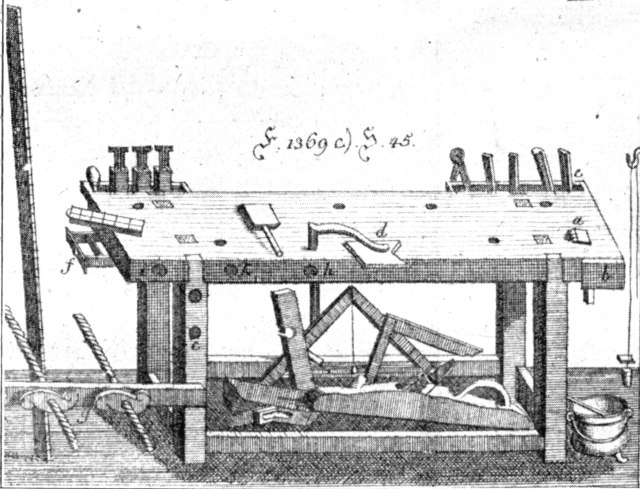

During our next open day for our storefront, Aug. 13, we’re throwing a special “reading party” for the forthcoming “Roubo on Furniture.” You’ll get an advance look at the book and get to read some of the great stuff the authors have dug up from “l’Art du menuisier.”

At the party, we’re going to have the translated text for all 97 plates of “Roubo on Furniture” printed out plus a big jar of red pens. To help, we’ll also have a bunch of copies of “The Book of Plates,” the original 18th century French volumes and my library of woodworking books, which includes a French woodworking dictionary.

Oh, and we’ll have free beer and snacks.

The storefront is located at 837 Willard St., Covington, Ky., 41017. Our hours for that day will be 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

If you can attend, we’ll set you up to look for typos or other errors in the text (we have found multiple cases where Roubo refers to the wrong figures in the plates and we are trying to clean that up). The text for each plate takes about 30 to 40 minutes to read carefully.

For every plate that you edit, we’ll give you a nicely printed commemorative postcard. And a free beer.

The text for this book has already been edited many times by the authors, Megan Fitzpatrick, Wesley Tanner and me. But we haven’t performed a final copy edit on the text where we root out all the nasty language gremlins. So your help with this will be greatly appreciated.

If you can attend, leave a note in the comments section so we know how much beer to bring.

I’m afraid we cannot do this over the Internet. We are not ready to send out this text into the unknown, where people can post it before it’s ready for the public. Apologies, but we’re immovable on that point.

— Christopher Schwarz