This is an excerpt from “The Art of Joinery” by Joseph Moxon with commentary by Christopher Schwarz.

Joseph Moxon’s text is in italics.

Of the square and it’s use.

The square, marked D, is two adjunct sides of a geometrical square. a The handle. b The tongue. c The outer square. d The inner square. For [a] joiner’s use, it is made of two pieces of wood, the one about an inch thick, and the other about a quarter of an inch thick. These two pieces are severally shot exactly straight and have each of their sides parallel to each of their own sides. The thick piece {called the handle} has a mortise in it as long {within a quarter of an inch} as the thin piece {called the tongue} is broad, and so wide, as to contain the thickness of the tongue. The tongue is fastened into the mortise of the handle with glue and wooden pins so [that] the two outer sides {and then consequently the two inner sides} may stand at right angles with one another.

The reason why the handle is so much thicker than the tongue is because the handle should on either side become a fence to the tongue. And the reason why the tongue has not its whole breadth let into the end of the handle is because they may with less care strike a line by the side of a thin than a thick piece: For if instead of holding the hand upright when they strike a line, they should hold it never so little inwards, [then] the shank of a pricker [an awl-like marking tool] falling against the top edge of the handle would throw the point of a pricker farther out than a thin piece would. To avoid this inconvenience, the tongue is left about half an inch out of the end of the handle.

Another reason is that if with often striking the pricker against the tongue it becomes ragged or uneven, they can with less trouble plane it again when the stuff is all the way of an equal strength [that is, same grain direction] than they can if crossgrained shoulders be added to any part of it.

Its use is for the striking of lines square – either to other lines or to straight sides, and to try the squareness of their work by. To strike a line square to a side they have already shot, they apply the inside of the handle close to the side shot and lay the tongue flat upon the work. Then [on] the outside of the tongue they draw with a pricker a straight line. This is called striking, or drawing of a square. To try the squareness of a piece of stuff shot on two adjoining sides, they apply the insides of the handle and tongue to the outsides of the stuff. And if the outsides of the stuff do all the way agree in line with the insides of the square, it is true[ly] square. To try the inward squareness of work, they apply the two outsides of the square to the insides of the work.

Analysis

Moxon’s explanation of the try square’s anatomy is fairly straightforward, though the description of the square’s tongue is a bit awkward, despite efforts to unscramble it. What Moxon is saying is that it’s easier to scribe a line against a thin tongue than a thick tongue. Why? You are less likely to miss your mark when you tip your awl (or knife or pricker) and place it against the tongue. If the tongue is thick, your error can be greater.

Moxon’s other two explanations for why the tongue is thinner are better: The handle can then be used as a fence against the work, and the tongue is easier to plane back to square after it becomes ragged.

I think Moxon also has made a small error here: He first implies the tongue should extend out of the handle 1∕4″. Then he says later it is 1∕ 2″ (which is the distance used by Roubo in his later work). It’s impossible to tell which is correct from the illustration.”

We also learn a bit about the pricker here, though it is not called out in the plates. (Could it be the bulbous tool shown beneath the dividers on plate 5? This tool is not on F.libien’s plates to my knowledge.) One guess is that the pricker is like a striking awl: A rod of steel sharpened to a point at one end that is used for striking lines for joinery.

The description of using the square is revealing: It implies that the inside and outside angles of the square should both be square. Some writers have suggested that only one or the other is important. Here Moxon is clear: The try square is square on both the outside and inside of its tongue and is used for both striking lines and confirming that your work is square, inside and out.

— Meghan B.

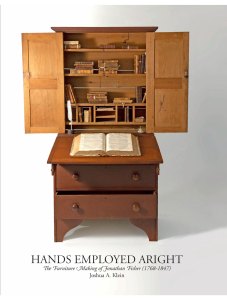

Mark your calendar for Saturday, Sept. 8. Joshua Klein of

Mark your calendar for Saturday, Sept. 8. Joshua Klein of