Robin Warman, host of “The Wild Dispatch,” has spent several episodes talking with Monroe Robinson, author of “The Handcrafted Life of Dick Proenneke.” Recently, Monroe and his wife, K. Schubeck, invited Robin and his wife, Hanneke, over for sourdough pancakes, made using Dick’s very own sourdough starter.

Watching the episode is an invitation to join them. From their home in Little River, California, Monroe cooks pancakes, while passing around a jar of homemade wild blueberry jam K. shares stories about her experiences in Alaska, and Robin and Hanneke ask insightful questions.

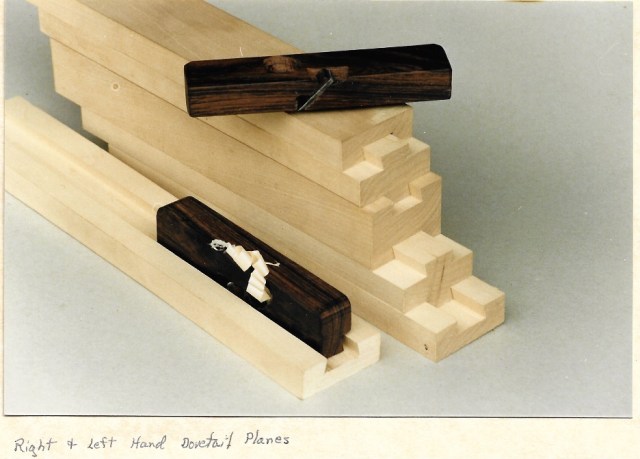

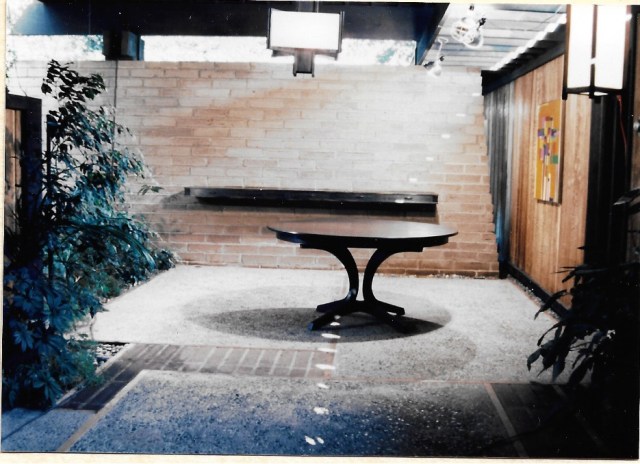

Once a pile of pancakes is complete, Monroe sits, eats and shares stories as well. Many of the people who have visited Dick’s cabin over the years were drawn to it, Monroe says, because it, and everything in it, was handcrafted. Monroe and K. spent many years as caretakers of the cabin, and Monroe built replicas of many of its contents. In doing so, Monroe discovered the spirit of Dick – particularly, his ingeniousness and determination.

Sitting around the breakfast table, K. remembers Monroe, after working all day on a replica, coming home and saying, “I got to know Dick Proenneke a lot better today.”

There’s intimacy in the things we make, no?

You can watch the full episode here. And you can listen to more conversations with Robin and Monroe in EP43, EP51 and EP61.

To end, here’s an excerpt from Monroe’s book, a journal entry written by Dick more than 30 years ago. Here, he mentions sourdough, likely from the same starter featured all these years later.

— Kara Gebhart Uhl

March 15, 1993

Clear, Calm and -8°.

Clear and stars looking down, it could get pretty cool tonight. The half gallon carton of vanilla ice cream set on the table out front and morning would find it about right for dishing it out. Zero degrees makes soft ice cream.

The fire was buried the whole night. I would have coals but puny ones. During breakfast I knew what I was going to do today. A good day to circle the mt. I had suggested it to Leon [Alsworth] and he said we will have to go on snowshoes. Maybe next week he could go but I was sure he wouldn’t. On those little Sherpa aluminum and plastic snowshoes I wouldn’t go. Only thing good about them is the ice claws for mt. travel. It was 9.30 when I closed the door. I would pack my snowshoes to the mouth of Low Pass creek. I had the Olympus OM1n with 50 and 28 mm lens. I was dressed cool for it would be a warm three hrs getting to the divide. That last 400 feet of elevation is as steep as a cows face.

I took a few frames from the mouth of Low Pass creek and then headed for the pass. No sign of porkypines at their winter home and now I wouldn’t know where to find one. I see no tracks.

I was breaking a deeper trail than I had expected. It would be a good climb up the trench to the pass. Old tracks of a wolverine headed or coming from the pass. I have seen porkypines in the pass making that slow hike to the Kijik country. In due time I was up there enjoying the view back down and across the lake. Lots of snow up there and I believe there is more snow in the bottom behind gold ridge than I have ever seen there. 1,700 feet from the lake is the gain in elevation when you climb to the pass. From the pass it is a gain of 1,300 feet to the summit where I would cross. No tracks not one as I traveled on. The fresh last snow laid like a cotton bat and about 6 inches deep on top of the settled snow pack. Just before I got to that last very steep pitch to the divide I came to a reasonably fresh wolf track coming down from the high ridge. Later I would see that track climbing up 1st canyon. So wolves cross there some times and so do wolverine for today I would see a wolverine track climbing to the 3,000 ft. ridge.

At last I stood at the base of that 400 ft. very steep climb. I would have to climb it without snowshoes so I put them on the light pack frame with my camera gear. The snow more than shoe pac deep but a base that was soft enough to give good traction. Traverse back and forth across a width of a couple hundred feet of the mt. Climb at a comfortable angle. Slow but steady does it and in due time I was up near the eye in the mt. I had looked for it as I climbed from Low Pass but couldn’t spot it. I found the snow so deep only a little of the eye was visible. At last I stood on the divide and the time a quarter till three. It had taken me more than five hrs from my cabin to the top 3,000 ft. up.

The sun was bright and a cool breeze had me looking for sun on the protected side of the ridge. I shot a few frames and ate my sourdough sadwich and one of Sis’s good cookies. Now it was down hill all the way to my cabin and about 2 hrs. steady going to get there. Steep for the 1st quarter mile. Now I learned what I once knew. Crampons can be necessary for that 1st quarter for the snow can be too hard to kick steps. Right there I should have turned back and down where I had climbed. I expected it to get better a hundred feet down. There is hard wind pack near the top. To play it safe I moved in the clear of rock outcrops below.

To lose footing and go pell mell down a steep pitch and hit a rock will spoil your day, but good. I was in the clear but footing was poor. If I started I wouldn’t stop for about 200 yds. And I started. I was using both hands on my good walking stick for a brake. Faster and faster and it was a pretty rough slide. My pack kept me from staying on my back and when I went side wise I started to roll. Ho Boy! All I could see was snow and blue sky revolving at a terrific rate. Presently I slowed and stopped. It had been the six inches of loose snow I was expecting higher up. It is surprising how much snow gets inside a tumble down the mt. My mittens were full. Snow inside my jacket. Didn’t lose my Bean cap with the ear flaps over my ears. Still had my pack on for I had hooked the rubber link across my chest. First thing I noticed was that my right upper arm pained a little. If it hurt so soon it wouldn’t hurt a lot more tomorrow. Legs were ok and that was good. If I had broken a leg it would be “sorry charley” you didn’t make it. Tonight would be well below zero. So I could put up with a sore arm and not complain. I discovered that I had lost my good walking stick. I looked for sign of it above and below. Even tried to climb but after climbing 50 feet I slid down 25. Tried again and just couldn’t get traction. So I got organized and headed down the mt. in the loose 6-8 inches of snow. When the incline flattened a bit I put on my snowshoes and came down the water course from the base of the steep going. I hadn’t gone far when I met a wolf track climbing to the divide. It was short steps and feet making drag marks in the loose snow for the wolf. Headed for the Kijik for I hadn’t seen tracks in the pass coming to the upper lake. Down, down but not so steep that I would lose control on snowshoes. At times I would support my right arm with my left hand. It was uncomfortable hanging free. Lower I came to a wolverine track climbing so it was going over the top. I find mr. wolverine just doesn’t seem to care how steep or rough it is. He doesn’t seem to appreciate an easy route.

Hope creek at last and from 1st canyon down it was nice going. Wished for my walking stick but managed without it. It was going to take just about 2 hrs. from the divide to my cabin and the sun would be just about ready to set directly behind the Pyramid mt.

I opened the cabin door and learn’d Leon had been here. A bag containing letters a package and two batteries for my Bendix “King” radio. I still had a very few coals under the ashes and fine stuff would have a fire going quickly. I wanted to auger the ice this evening for I might not do it so easy tomorrow. I found it 27″ this 15th of March. Did my chores with little difficulty and got out of my damp hiking clothes. How would my journal entry go with that gimpy right arm. It has worked better but I managed better than I expected. I’ll take an “Ascription” at ladder climbing time. Now 10.30 Clear, calm and -3°.

— Dick Proenneke