May is, of course, peak box turtles-crossing-the-road month. Here’s one that managed to evade Chris’s car:

This individual is of the “eastern” subspecies of common box turtle (Terrapene carolina).

I mentioned last month that I wasn’t able to find a good example of a black maple (Acer nigrum). Naturally, I came across a perfect example the very next day. Unfortunately, that tree was inaccessible; I would have had to climb down a steep slope into a swamp to be able to collect a leaf. I did eventually find another one:

Notice that it looks a bit like a seriously overweight sugar maple; the lobes are broad, the sinuses between lobes are very shallow, and the two outermost lobes have all but disappeared.

I also mentioned last month that the leaf of the boxelder (A. negundo) is disturbingly similar to that of eastern poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans). I came across this tableau in Ottawa County, along Lake Erie in northern Ohio:

The leaf circled on the left is poison ivy; the one on the right is boxelder.

A common maple lookalike of a different sort is American sycamore (Platanus occidentalis):

In the UK, what we call sycamore is called plane or planetree, and what they call sycamore is a maple, A. pseudoplatanus. And this is why I always give the scientific names </rant>.

Even with the scientific names, it can be a puzzle. Note the sycamore maple’s scientific name, Acer pseudoplatanus: “maple that is a fake plane.” London plane is a common ornamental tree in the UK that is hybrid between American sycamore and oriental planetree (P. orientalis). It is sometimes given the scientific name Platanus orientalis var. acerifolia (“eastern plane with maple-like foliage”). No wonder people get confused.

Several Ohio trees bloom in May. The northern catalpa (Catalpa speciosa) is uncommon in the wild around here, but frequently planted for its abundant showy flowers:

The native range of northern catalpa is uncertain. It was once thought to be native only to a small area of the Mississippi River drainage, between Arkansas and southwestern Indiana, but recently discovered archeological evidence from West Virginia suggests that it was present in the Ohio River drainage near here prior to European settlement.

Willow flowers aren’t showy, but there are enough of them that, from a distance, they give the trees an overall yellow fuzzy appearance. Here are some black willow (Salix nigra) flowers:

In North America, most legumes (family Fabaceae) are non-woody herbs. In the tropics, however, legumes are often trees, and some of the most highly prized tropical hardwoods, such as the rosewoods (Dalbergia), are in fact legumes. There are a few North American legumes that reach tree size, but only the mesquites (Prosopis) are traded commercially to any significant extent. Legumes often have showy flowers, and the North American species with perhaps the showiest is the black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia):

The bark of the black locust is pale gray with a greenish tint, arranged in thick, vertical ropes:

Most legumes have compound leaves of one sort or another. The leaves of the black locust are pinnate, having a central axis (the rachis), with elliptical leaflets along either side:

The other North American tree called locust, honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos), is actually not all that closely related to the black locust. It is most easily recognized by its formidable thorns:

(You can also see a flower bud near the center of the photo; in contrast to the black locust, the honey locust’s flower doesn’t get much bigger than what you see here.)

The bark is much smoother than that of the honey locust, but the thorns give it away:

(Note that there are thornless cultivars that are planted as ornamentals, so a tree that looks like a honey locust but doesn’t have any thorns is probably one of these.)

The leaves are bipinnate, meaning that the leaves are pinnate, and the leaflets are as well:

Although it’s not too common in Ohio, the Kentucky coffeetree (Gymnocladus dioicus) is also a legume, with enormous bipinnate leaves, up to three feet long. I know where there are some Kentucky coffeetrees nearby, but none with leaves close enough to the ground for me to reach, and in any case I don’t have a gray card big enough to lay one on.

There is an American legume with significant commercial value, but it’s not a North American tree:

This is the koa (Acacia koa) of Hawaiʻi. What appears to be a leaf is actually a structure that emerges as a swelling from the petiole (leaf stem), called a phyllode. Most mature koas have no true leaves at all, but in younger trees, you can usually find a few leaves in the interior of the tree, and they have the familiar legume appearance:

(I took these photos on Kauaʻi several years ago.) The closest relative of koa is Australian blackwood (A. melanoxylon), which also has phyllodes.

The eastern redbud (Cercis canadensis), which we first encountered back in March, also has attractive flowers. Those are long gone by May, but the seed pods are ripening:

It is said that the young pods can be cooked and eaten whole, like snow peas, but I have never tried them. Every year, by the time I think of it, they’ve gotten too old.

Unusual for a legume, the redbud has simple, heart-shaped leaves:

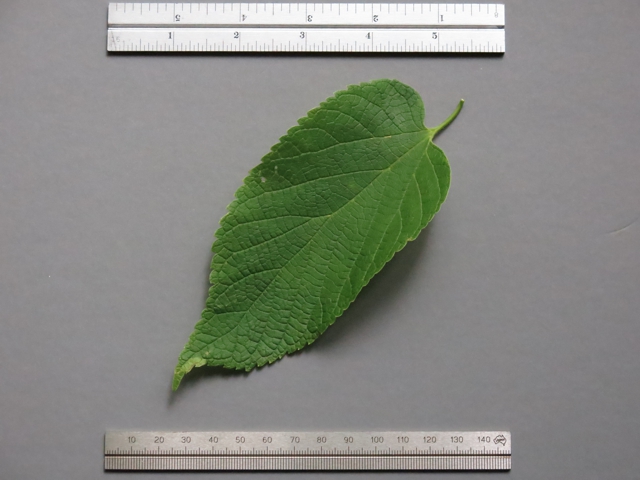

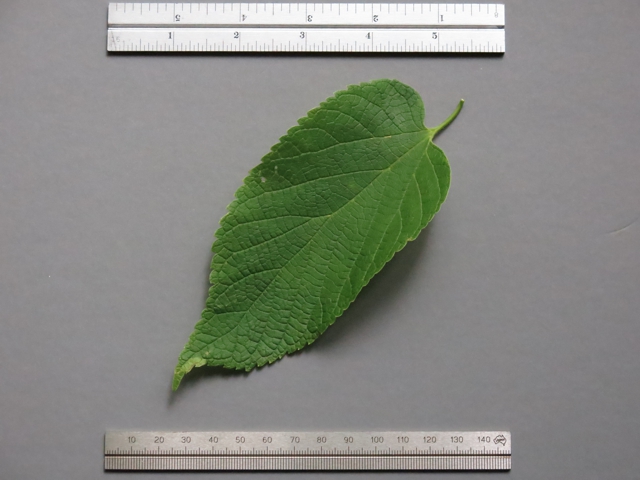

Another tree of the local forests with heart-shaped leaves is American basswood (Tilia americana):

If you look closely, you can see that the leaf is somewhat asymmetrical near the base, with one side reaching further back than the other. I don’t know why this is, and not all of the leaves are like this, but it’s a feature that is shared by several other unrelated trees.

Elms have asymmetrical leaves, too. Here is a slippery elm (Ulmus rubra):

(It’s a little hard to see the asymmetry in this one.)

And an American elm (U. americana):

The leaves of the slippery elm are densely covered with fine, stiff hairs. If you place one on a tabletop and press the palm of your hand flat against it, it will stick to your hand like Velcro. American elm leaves are usually much less hairy, but can sometimes look almost identical to slippery elm leaves. The easiest way to distinguish the two is to look at the stem between the leaves. In slippery elm, this stem is hairy:

In American elm, it’s smooth:

Another tree whose leaves have this same kind of asymmetry is the common hackberry (Celtis occidentalis):

Hackberry trees are easy to identify from their bark, covered with warty protuberances:

Unfortunately, the emerald ash borer has reached Athens County. I would estimate that over half of the larger ash trees are already dead or nearly so; the smaller ones seem to be hanging on a bit longer. Here’s a dead white ash in Ottawa County; you can see how the beetle larvae eat through the cambium in such a way as to cut off the tree’s nutrient supply:

The more common species here is green ash (Fraxinius pennsylvanica). The leaves are pinnate, usually with seven leaflets:

The leaves of white ash (F. americana) are very similar:

With a leaf in hand, however, there is a simple way to tell the two apart. If you look closely at the base of the petiole, where the leaf attaches to the branch, the cross section of the green ash’s leaf is roughly circular, with a small cutout on top:

While the white ash’s petiole has a much deeper groove:

Rare in Athens County, but more common to the north, the leaves of the black ash (F. nigra) usually have nine leaflets (sometimes more), rather than seven. There is a large tree on our land in Meigs County that I think is a black ash, but the tree is so tall that I can’t get a decent look at the leaves, even through binoculars.

The seeds of both local ashes are encased in samaras that remind me of surfboards:

By May, the forest floor is pretty dark, so there’s not that much going on as far as wildflowers are concerned. Some species occur around forest edges, where there’s more light. One of the common May wildflowers in my yard (but strangely absent in other places that would seem to be appropriate for them) is foxglove beardtongue (Penstemon digitalis):

The flowers that we usually think of as roses are all Asian imports, but there are a few native species, like this Carolina rose (Rosa carolina):

Venturing a bit deeper into the shade, we can find touch-me-nots, especially common along roadside ditches. This one is a pale touch-me-not (Impatiens pallida):

The name comes from the fact that the ripe seed pods are spring-loaded. If you squeeze one, it explodes, shooting seeds in all directions. (It’s a good practical joke when you’re out in the woods with someone who isn’t familiar with the flora: “Here, squeeze this between your fingers.”)

This one is limestone bittercress (Cardamine douglassii):

It also goes by the name “purple cress,” but there are a gazillion other flowers that also go by that name.

In the deepest shade, we can find Canadian wildginger (Asarum canadense, unrelated to culinary ginger):

You have to get down on your knees to see the flowers, though; they’re hidden below the leaves and practically buried in the leaf litter:

One of the most attractive spring/summer ferns is the northern maidenhair (Adiantum pedatum):

There is also a more southerly species called common maidenhair, which looks quite different, but I wasn’t able to find one. Maybe later this year.

When you’re walking in the woods, it pays to look down, and not only for wildflowers and ferns. I almost stepped on this (Odocoileus virginianus) when I went to fill the bird feeders in my backyard a few weeks ago:

–Steve Schafer

Like this:

Like Loading...