I’m used to working up a sweat while involved in some heavy sawing or planing, but what I’m not used to doing is gasping for air and getting a pounding headache in the process.

The Andes are big mountains, and Quito is one of the highest-elevation metropolitan areas in the world. Fortunately, we are living in the suburb of Tumbaco, which is about 1600 ft lower in elevation than Quito proper. Unfortunately, that means that we’re still at 7800 ft.

The traditional treatment for symptoms of altitude sickness is mate de coca, or coca leaf tea. In Peru, commercially produced mate de coca, in teabag form, can be found just about anywhere, and in the higher elevation cities like Cusco, you can purchase large plastic bags of the dried leaves for only a few dollars. Just about every hotel in Cusco has a bowl of coca leaves and a pot of hot water in the lobby for you to brew your mate. Strictly speaking, I don’t think the bulk leaves are legal, but nobody seems to care (probably because they’re all drinking mate).

Mate de coca is far less common in Ecuador, apparently because of greater influence from U.S. Government policymakers. There is some tension between its classification as a harmful drug and its traditional use as a natural medicinal/spiritual plant. You won’t see mate de coca in a supermarket, but you can find it if you look. (I know of a specialty gourmet coffee and chocolate shop in Quito that stocks it, for example.) The only place I’ve seen whole leaves is at the market in Otavalo, and even there it’s in itty-bitty little bags.

The active ingredients in mate de coca are cocaine and related alkaloids (of course), as well as methyl salicylate, which is chemically similar to aspirin and has analogous pain-relieving properties.

Does it work? It seems to, although it might be that it’s the methyl salicylate that’s doing the bulk of the work, rather than the cocaine. Consuming mate de coca does have a couple of noticeable additional consequences: For one thing, it has an energizing effect (which the Incas used to advantage when they wanted their slaves to work harder). It also inspires confidence, which can be a good thing when one is immersed in artistic pursuits, but is probably not such a great idea while working with tools having very sharp edges. So for woodworking, I think I’ll stick to acetazolamide and ibuprofen.

–Steve Schafer

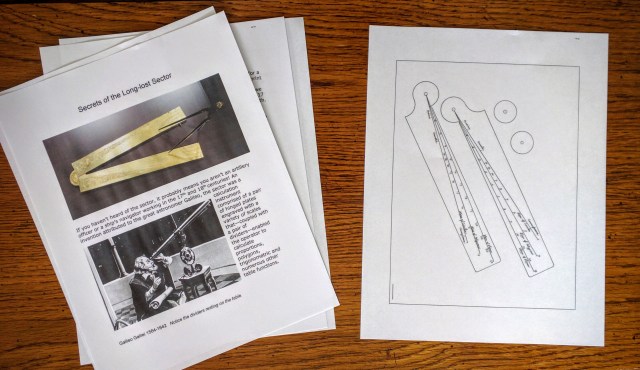

By the late 1700s, documents show that the sector was also taken up by architects and artisans to lay out designs based on the once ubiquitous whole-number segmentation and ratio-proportioning system of their trade. However, as 19th century machine-based manufacturing eclipsed the traditional practices of the artisans, their design and layout tools – dividers, sectors and applied Euclidian geometry in general – faded almost entirely from use.

By the late 1700s, documents show that the sector was also taken up by architects and artisans to lay out designs based on the once ubiquitous whole-number segmentation and ratio-proportioning system of their trade. However, as 19th century machine-based manufacturing eclipsed the traditional practices of the artisans, their design and layout tools – dividers, sectors and applied Euclidian geometry in general – faded almost entirely from use.

I won’t lie to you. For the last four months I’ve felt like my psyche has been muddled in a mortar and pestle.

I won’t lie to you. For the last four months I’ve felt like my psyche has been muddled in a mortar and pestle.