After all the returns and exchanges, we have five black chore coats ready to ship – four XXLs and one L. They are available here if you hurry.

— Christopher Schwarz

After all the returns and exchanges, we have five black chore coats ready to ship – four XXLs and one L. They are available here if you hurry.

— Christopher Schwarz

Speaking as someone who has read too many woodworking books, there are a few archetypes: the project book (“Birdhouse Bonanza”), the tool book (“Router Rodeo!”) and the black-turtleneck-and-beret books on why me make things (“My Mortise is Deeper than My Soul”).

Nancy Hiller’s new book “English Arts & Crafts Furniture” is none of these books. But you probably knew this because Hiller’s name is on it.

Instead “English Arts & Crafts Furniture” is one of those rare books that rewrites the history of the Arts & Crafts movement (it’s not just a reaction against industrialization – plus slats ‘n’ oak) while making you laugh and occasionally blush. She delves deep into the personalities that shaped the movement – John Ruskin and William Morris, plus the makers Harris Lebus, Ernest Gimson and the Barnsleys. And she presents three projects that are directly tied to her narrative thread.

It’s quite a trick, actually. It turns out that Hiller has written a project book with some very good information on tool use that happens to make me wonder about my motivation for making furniture for sale (now, where did I put my beret?).

Among her other feats of legerdemain: Hiller’s research is impeccable and copiously footnoted, yet the book is a breezy read. Despite the high level of craftsmanship displayed in her project pieces, Hiller manages to slough off her ego by profiling all the people who helped her along the way to make these incredible works – the stained glass maker, the woman who made the rush seats, the guy who make the hardware for her sideboard. And she manages to pack an incredible number of ideas and beautiful images into a book that is just 144 pages long.

If the book has any failings, I’d say that the illustrations could be improved. While there’s enough information to build the projects (and that’s all that matters), the line drawings don’t match the gorgeous photos, layout and typography. The book has some beautiful and expensive touches – the full-color endsheets match the wallpaper on the cover – but I kind of gag when I see advertisements bound into the back of a book. Those, however, are personal problems.

In all, this is a rare woodworking book. The kind of book that makes me jealous that I didn’t write it myself. (Or at least come up with Hiller’s fascinating way of combining biography, history, sociology, workshop instruction and butt jokes.)

So buy it, even if you think you don’t like English Arts & Crafts (though you probably will after seeing the movement through Hiller’s eyes). And buy it because it supports this kind of work that has become rare in the woodworking field. Most woodworking books these days have more gimmicks than gumption.

“English Arts & Crafts Furniture” is available from ShopWoodworking and other retailers. However, Hiller will make more money if you buy it from ShopWoodworking or directly from her at her upcoming book tour.

— Christopher Schwarz

P.S. If you are particularly charmed by the side chair in the book, Hiller will offer additional plans of the chair. Those will be available through her website.

Our warehouse began shipping pre-publication orders for “Welsh Stick Chairs” yesterday and is working on getting the remainder out in the mail today.

I’m going to be a bit of a wiener here and say that I think our edition exceeds the quality of all the previous editions. This had little to do with me and everything to do with our prepress agency, the special printing press we used for this job and the press operators.

In comparing the images among all the editions of “Welsh Stick Chairs” I own, I can find no image degradation in ours. The text is, of course, super crisp because we reset the entire thing using the original fonts and line spacing from the first edition (even replicating a number of typesetting errors in the interest of accuracy).

The biggest manufacturing improvement is that we sewed the signatures in addition to bedding them in adhesive, making for a permanent book.

John Brown’s words are, of course, the same and cannot be improved upon.

Even if you decide to pass on purchasing this book, don’t worry. We’ve made sure our edition will be around for generations to come when you (or your children) decide to pick up a copy.

“Welsh Stick Chairs” is $29, which includes domestic shipping (yes, even to Alaska and Hawaii).

— Christopher Schwarz

All pre-publication orders placed through the Lost Art Press store will receive a pdf download of the book at checkout. After the book ships, the pdf will cost extra.

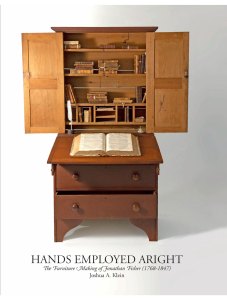

“Hands Employed Aright” is the culmination of five years of research into the life of Jonathan Fisher. Fisher was the first settled minister of the frontier town of Blue Hill, Maine. Harvard-educated and handy with an axe, Fisher spent his adult life building furniture for his community. Fortunately for us, Fisher recorded every aspect of his life as a woodworker and minister on the frontier.

In this book, Klein, the founder of Mortise & Tenon Magazine, examines what might be the most complete record of the life of an early 19th-century American craftsman. Using Fisher’s papers, his tools and the surviving furniture, Klein paints a picture of a man of remarkable mechanical genius, seemingly boundless energy and the deepest devotion. It is a portrait that is at times both familiar and completely alien to a modern reader – and one that will likely change your view of furniture making in the early days of the United States.

This hardbound, full-color book will be produced entirely in the United States using quality materials and manufacturing methods. You can get a sample of the writing, photography and design of the book via this excerpt.

You can place your order for “Hands Employed Aright” here.

— Christopher Schwarz

P.S. As always, we do not know which of our retailers plan to carry this book – it’s their decision; not ours. We hope that all of them will stock it. Contact your nearest retailer for more information.

A fair number of the stick and staked chairs that I make lack stretchers between the legs. But some of my chairs have them. So I get asked regularly: When do you use stretchers and why?

The simple answer is I add stretchers when the customer wants them. But that’s not a helpful answer for those getting started in designing and building chairs.

First a little history: Chairs don’t have to have stretchers to survive. I’ve seen plenty of chairs that have survived 300 years or more without stretchers. And yet, because most modern chairs have stretchers, a chair can look odd or alarming without them.

Stretchers add rigidity to the undercarriage and make the lower area of the chair visually balanced with the stuff above the seat – the spindles, arms and other hoo-ha. And they really aren’t a lot of labor to add to a chair. I’d guess that the stretchers add about an hour to the construction time of a typical chair.

So I guess the question then becomes: Why would you omit stretchers? A lack of raw material? Stylistic reasons? A lack of skill by the maker?

I think those reasons are unlikely.

The best explanation I’ve read is in Claudia Kinmonth’s “Irish Country Furniture: 1700-1950” (Yale). She begins her explanation with a description of the damp and earthen floors in a typical cottage. Then she adds:

Uneven floors have a bad effect upon seats with legs rigidly joined by stretchers. Except for mass-produced chairs, the majority of locally made stools and chairs had independent unlinked legs, which could be individually removed and replaced by the householder whenever they become worn or loose. This lack of stretchers combined with the common use of the through-wedged tenon to attach the legs to the seats, meant that chairs could survive inclement periods for long periods.

Kinmonth then goes on to describe several historical examples of stools and chairs that have had repairs.

To me, ease of construction and repair makes the most sense. If anyone else has a better explanation, you know what to do.

— Christopher Schwarz