You know that this post is going to be about André-Jacob Roubo. But not entirely.

For me, woodworking books in the French tradition begin with a title we haven’t been able to publish from the “other André” – André Félibien’s “Des Principes de L’Architecture…” (1676). Félibien’s book, which includes sections on woodworking, was published before Joseph Moxon’s “Mechanick’s Exercises.” And Joseph, the naughty Englishman, ripped off many of Félibien’s images for his book.

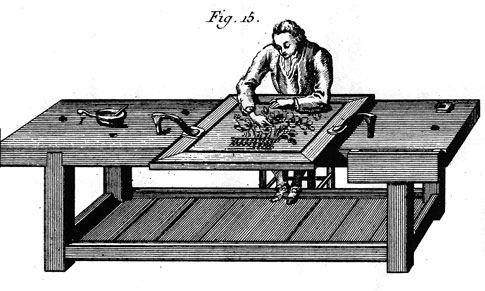

We have attempted to translate this book on a couple occasions, but the effort has always drifted off track for one reason or another. I’d like to get it published because Félibien’s book illustrates the first instances of the double-screw vise (what we call a Moxon vise), the goberge clamping bars, a sliding deadman and a marquetry donkey (among other innovations).

Another Book We Don’t Publish

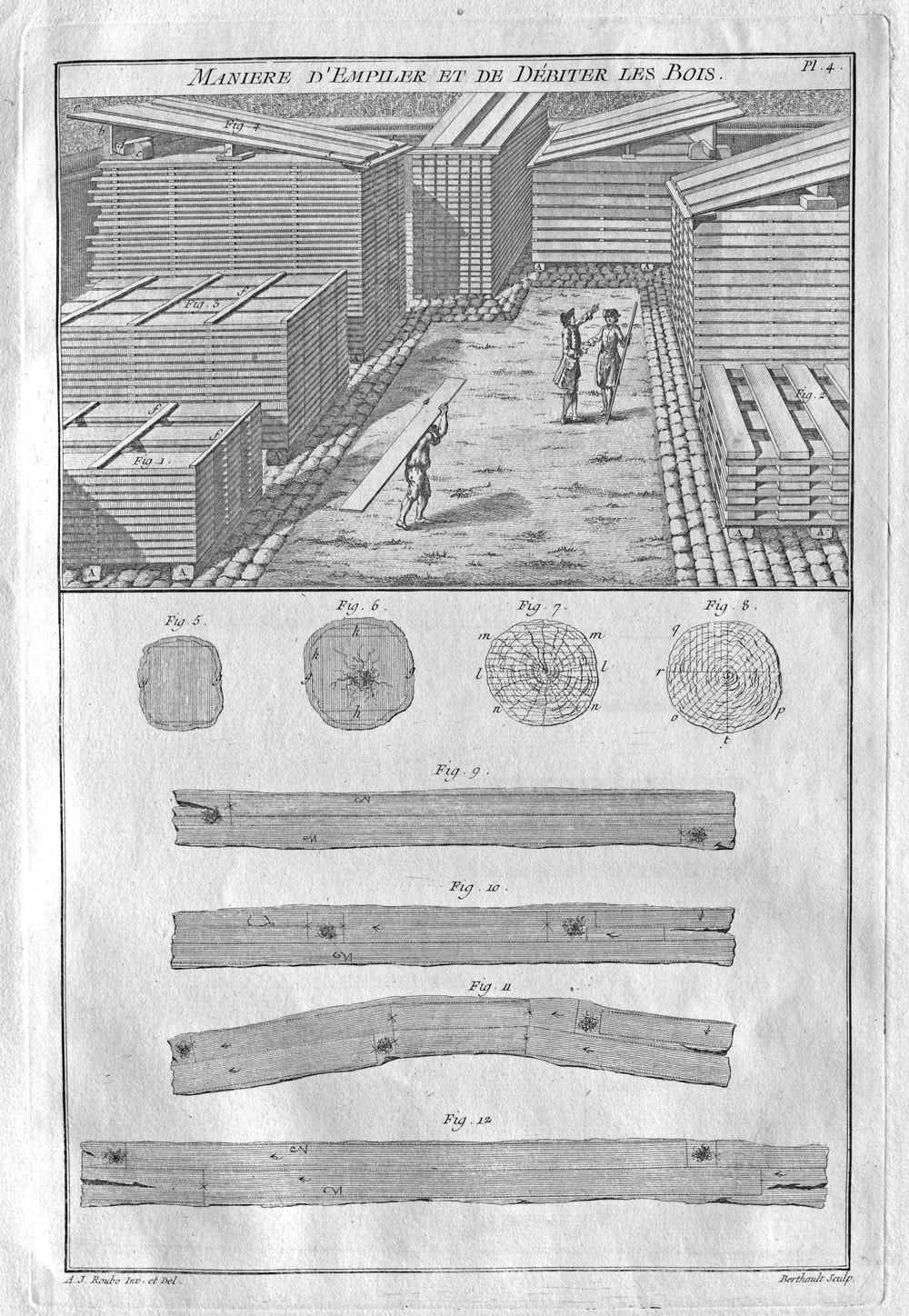

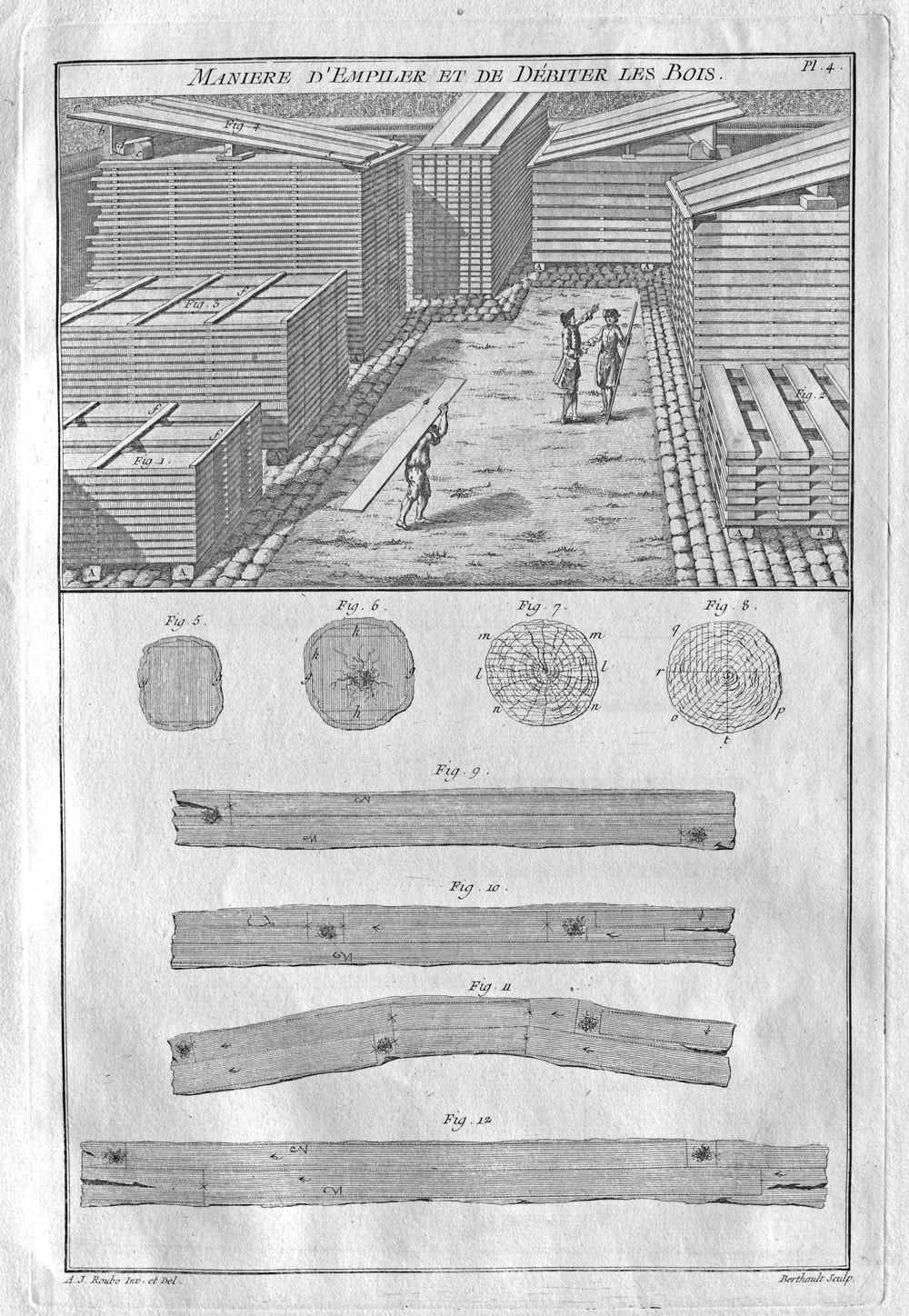

Also important in the French canon is M. Duhamel’s “De L’Exploitation Des Bois” (1764). This is, as far as I can tell, the first book devoted to what we now call “green woodworking.” It deals with the seasoning of wood and explains wood movement using the same charts we use today. It covers making all sorts of things from green wood, from shoes to the frames for saddles. It covers wood bending and a wide variety of techniques.

We’ve started on this project a few times and it has proved to be a challenge. Someday.

And Another…

You can’t really discuss French technical books without mentioning Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert’s “Encyclopédie,” a 32-volume work that covered, well, everything. It was an encyclopedia after all. There are sections on woodworking and the allied trades. But I find the “Encyclopédie” too general for me to own a set.

OK, Now Roubo

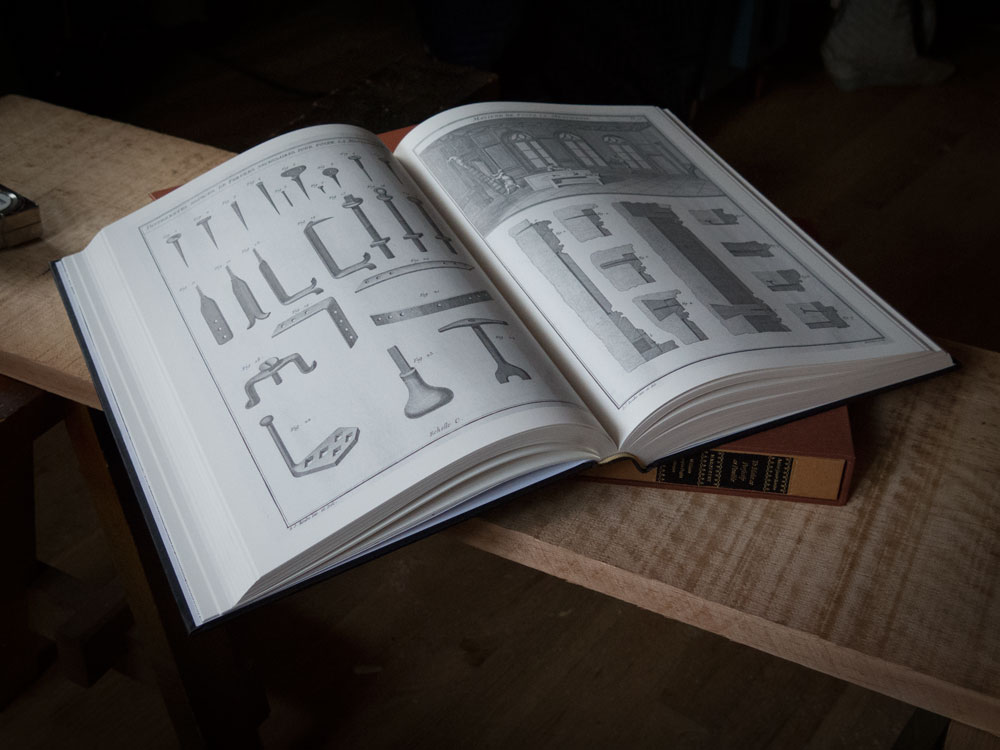

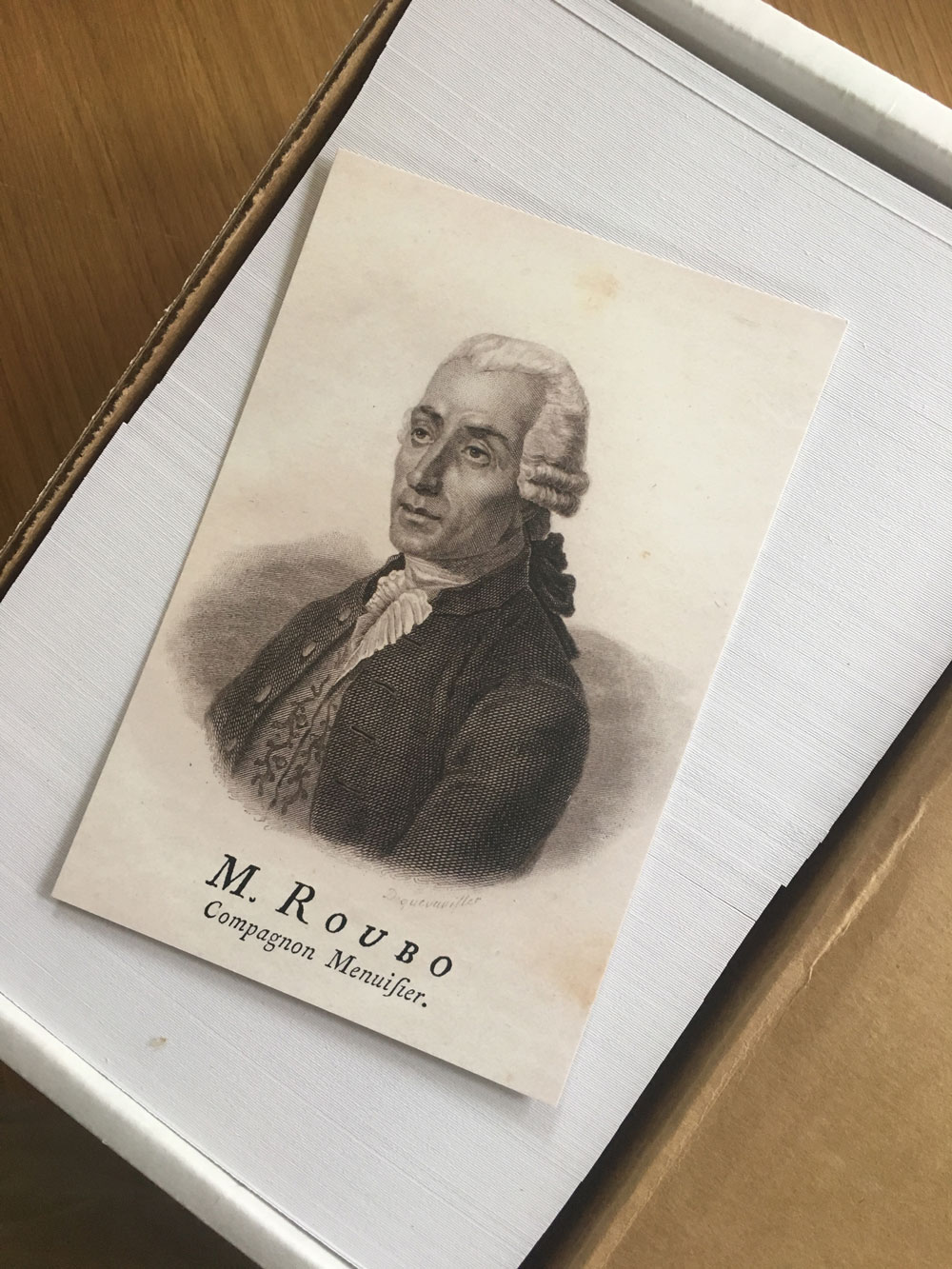

A group of us have devoted a ridiculous amount of time and money to translate large chunks of Roubo’s “l’Art du menuisier,” which is an enormous multi-volume set on woodworking, joinery, furniture-making, marquetry, carriage making, garden woodworking, turning, finishing and many other topics of interest to the contemporary woodworker.

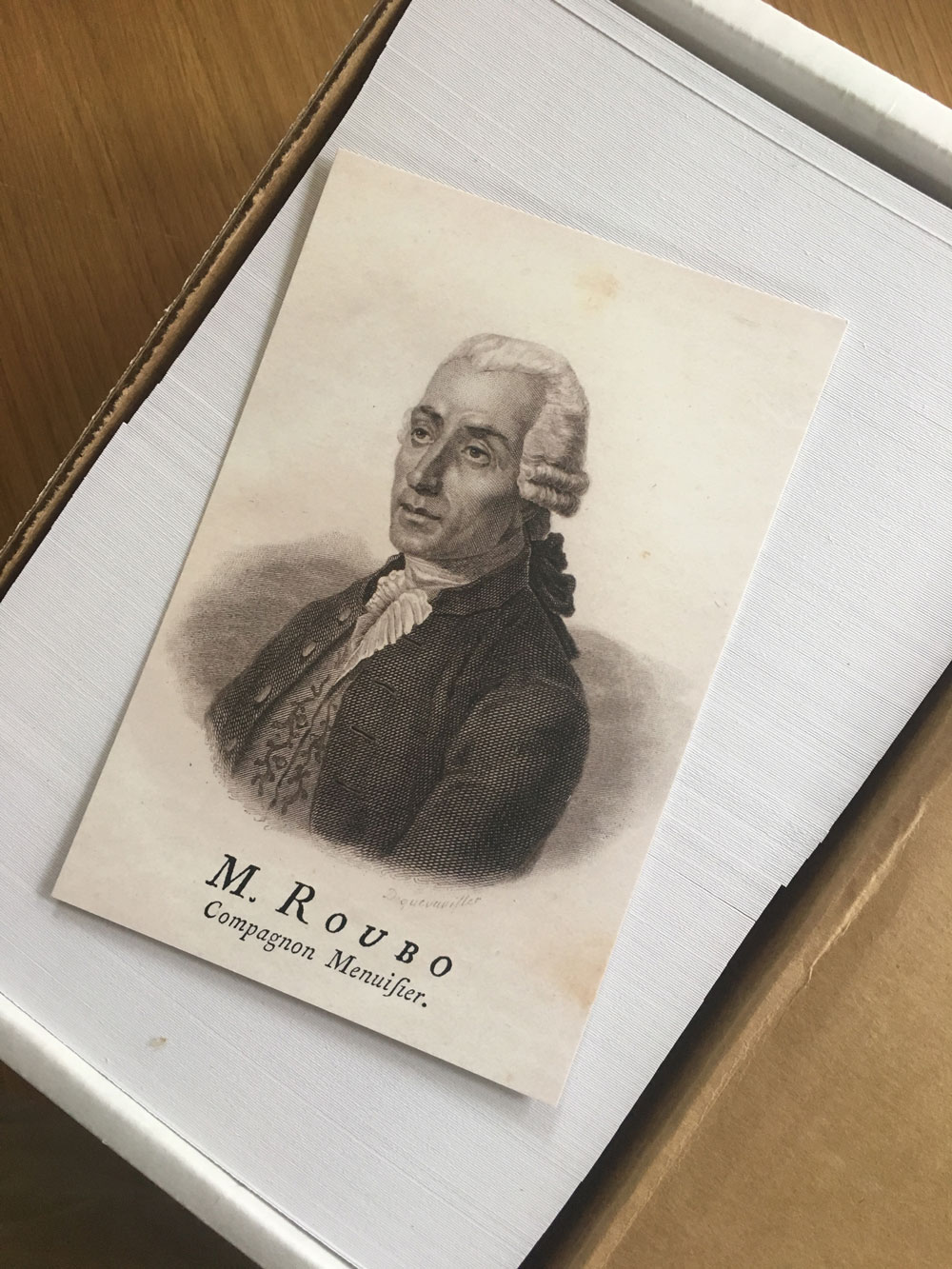

Unlike the other authors above, Roubo was a practicing joiner who studied architectural drawing at night (he drew the illustrations for his books) and interviewed fellow craftsmen to create his masterwork, which earned him a promotion from journeyman to master.

At times I think I am too close to this work and cannot adequately explain how completely intoxicating and challenging it is. Many woodworking books (even the ones I write personally) are fairly tame stuff, intellectually. While modern books help you grow a bit, Roubo is more like diving in headfirst to Thomas Pynchon right after mastering “Dick & Jane.” If you are willing to pay attention, you will be rewarded with nuggets of knowledge you can’t find elsewhere. Roubo has helped me directly with my finishing, the way I prepare glue, my understanding of campaign furniture, how I make brick moulding, designing galleries and on and on.

And I seriously doubt I’ll ever build a high-style French furniture. It’s not a book of projects.

We have two translated volumes that reflect a decade of work by Donald C. Williams, Michele Pietryka-Pagán, Philippe Lafargue and a team of editors and designers.

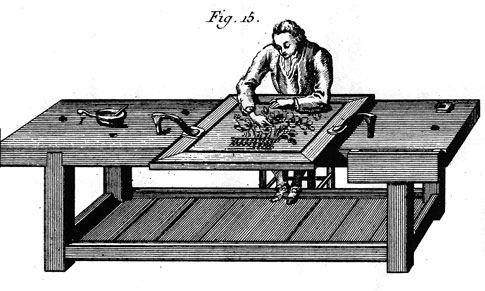

The first, “To Make as Perfectly as Possible: Roubo on Marquetry” covers wood selection, marquetry, glue, veneer and finishing.

The second volume, “With All the Precision Possible: Roubo on Furniture,” covers all of Roubo’s writing on making furniture, plus the workshop, workshop appliances, tools and turning. This book is massive, and even though I’ve read it many times over, I refer to it regularly and consider it one of the foundations of my work.

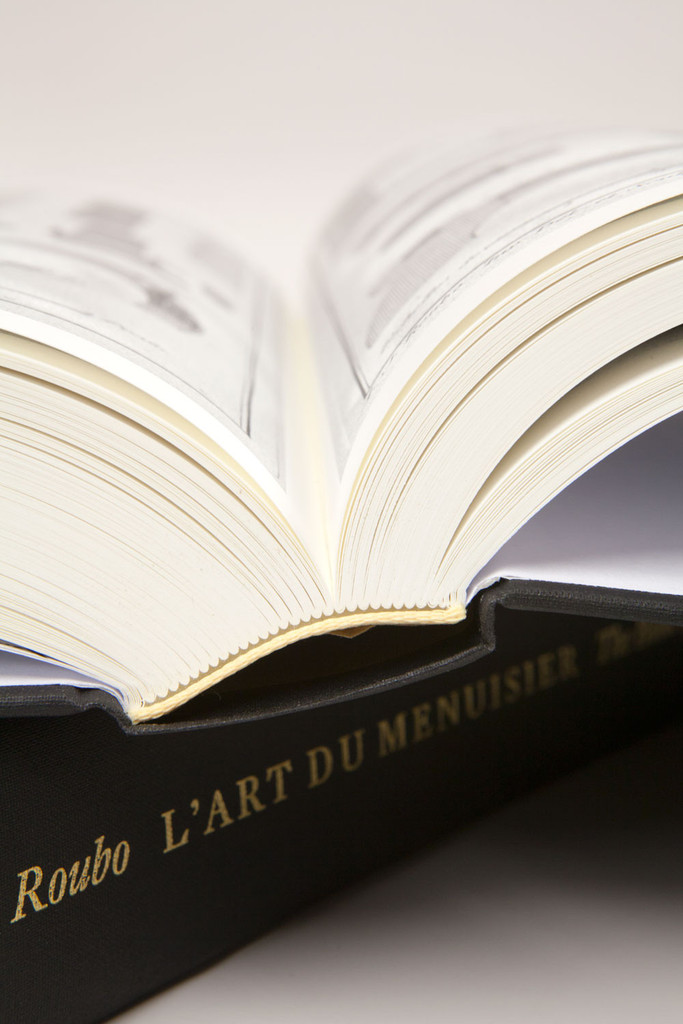

Because we are insane, we also published a deluxe version of this book. It is $550. It is the nicest thing in the world that has my name in it. Carrying this book around is like lugging two giant pizzas to your car. Sitting down and reading it with a glass of bourbon is one of the greatest pleasures I know of.

I do love it. But still, it was a nutty thing to publish.

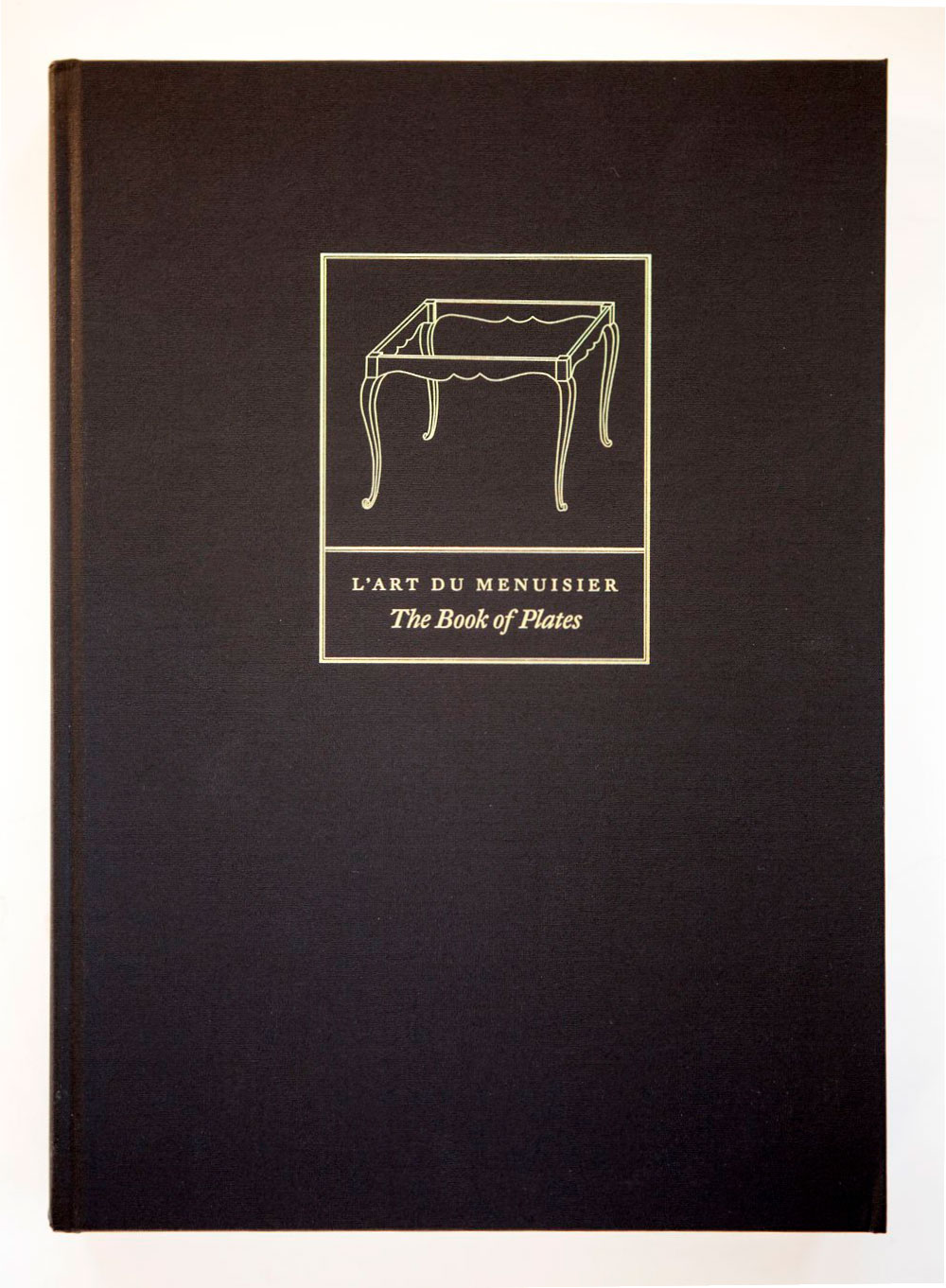

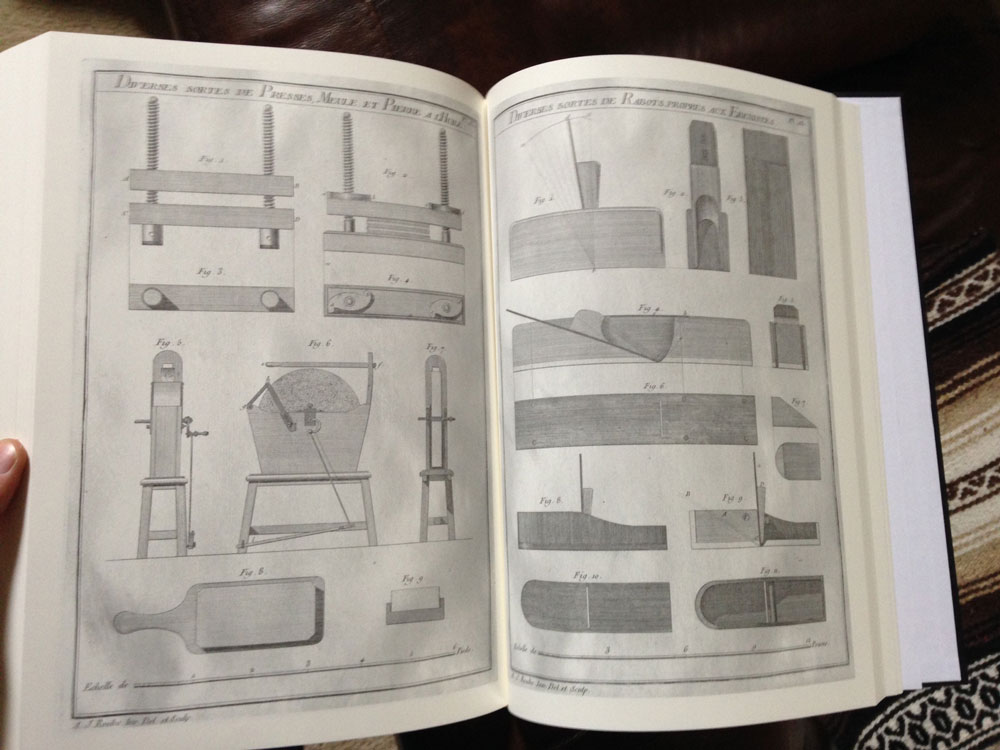

Slightly less nutty (but still up there) is “The Book of Plates.” This book reproduces all of the plates from Roubo’s books in full-size. This is a great companion if you buy a pdf of one of the two translations or happen to read ancient French.

And Finally

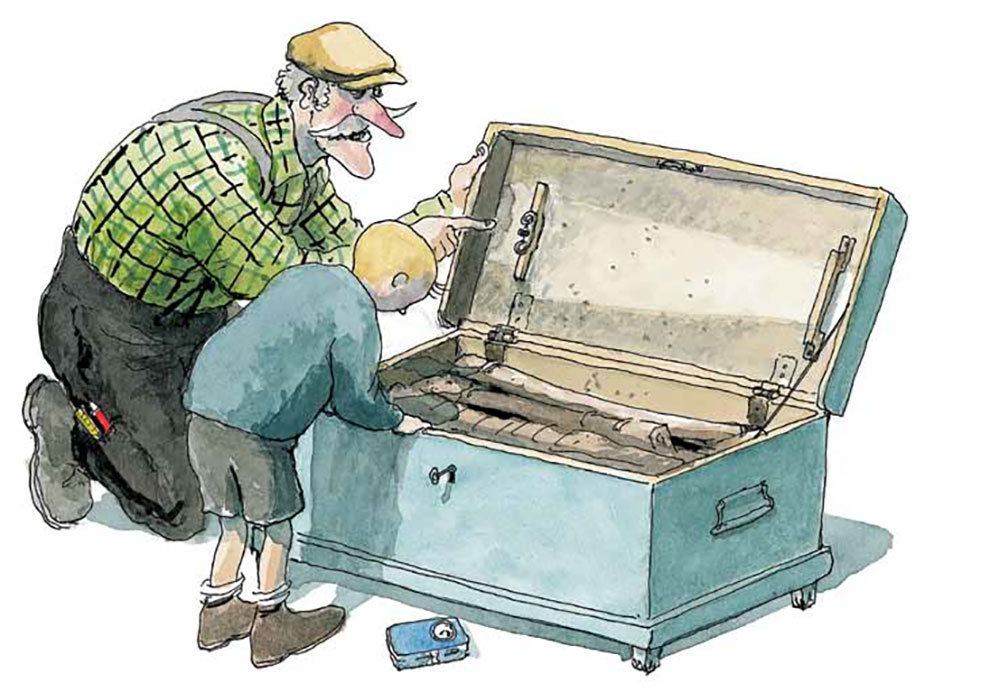

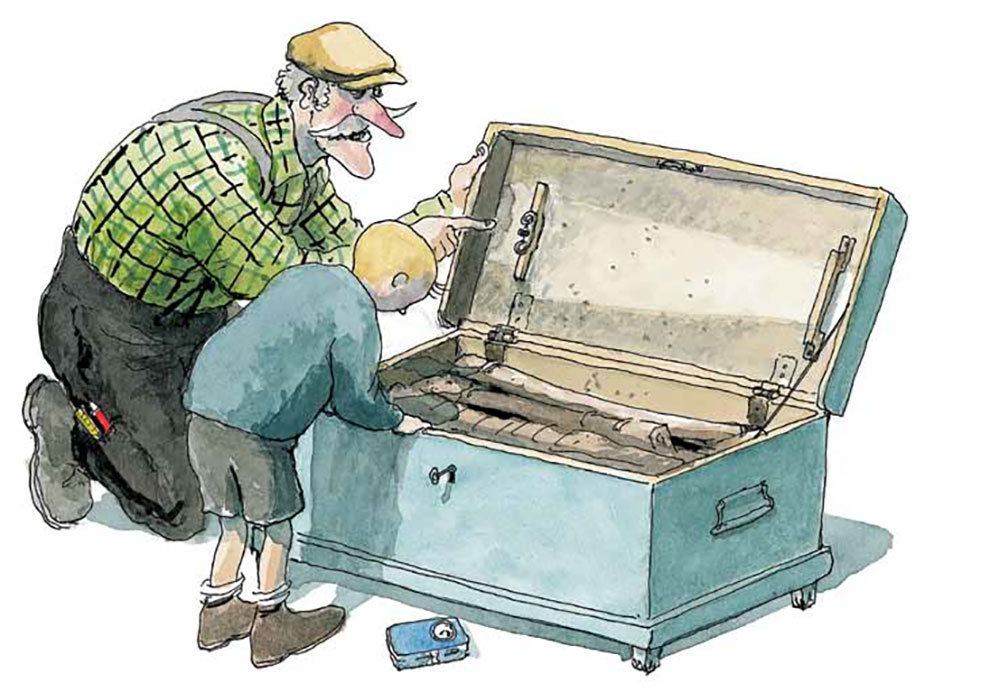

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention “Grandpa’s Workshop” by Maurice Pommier, perhaps our most charming book. Ostensibly a children’s tale, it’s a delightful collection of illustrated stories about woodworking, craftsman and slaying dragons with a mortise chisel.

It’s a bit scary for overprotective parents (there’s a murder). But the rest of you will be delighted because Pommier is a devoted hand-tool woodworker. And so all the woodworking bits are perfectly rendered by someone who knows how to handle the tools. It is, to me, a pure delight to read.

— Christopher Schwarz

Like this:

Like Loading...