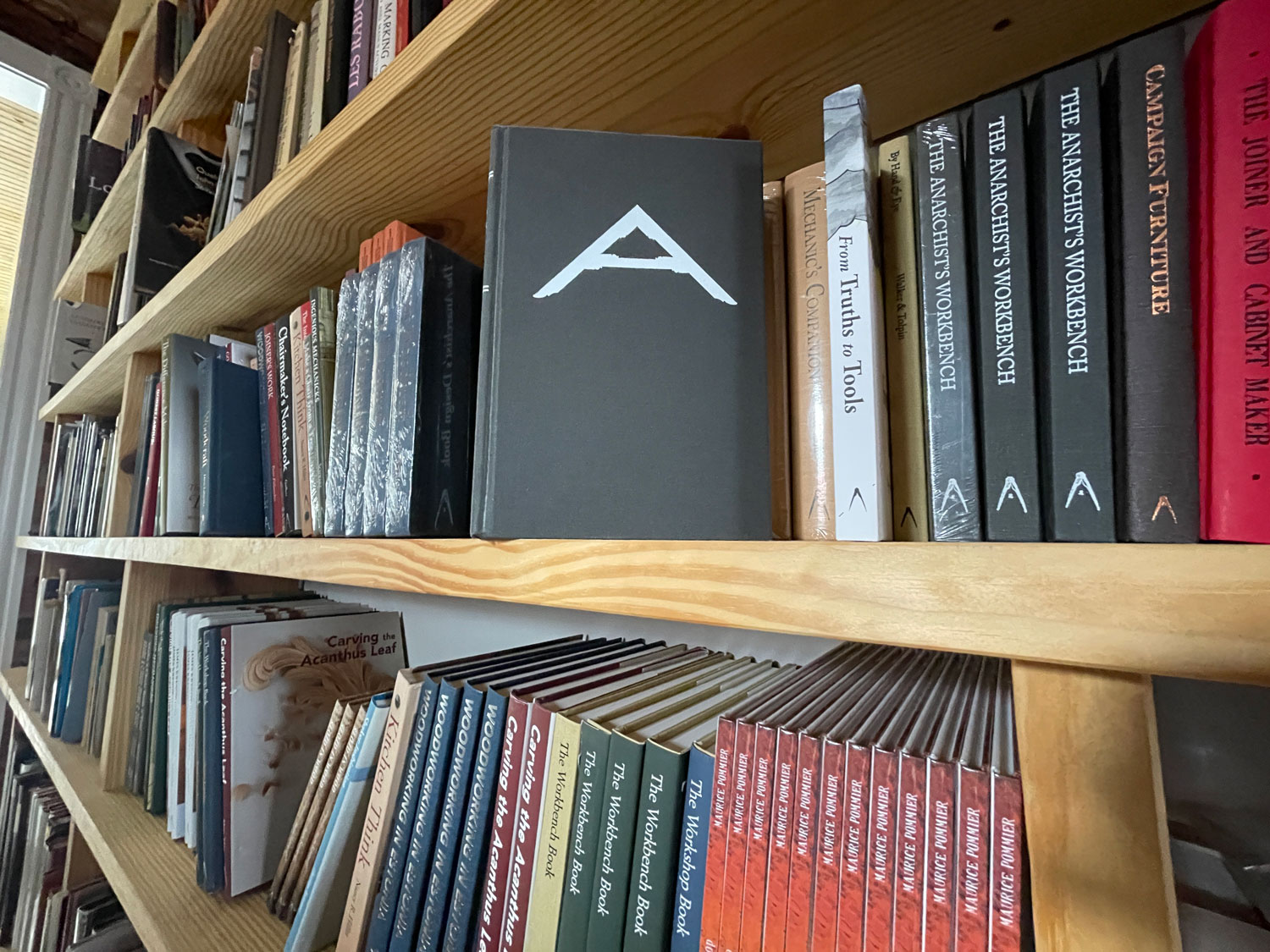

The following is excerpted from Nancy R. Hiller’s “Kitchen Think: A guide to design and construction, from refurbishing to renovation.”

For two decades, Nancy made a living by turning limitations into creative, lively and livable kitchens for her clients. This, her final how-to book, is an invitation to learn from both her completed kitchen designs (plus kitchens from a few others) and from the way she worked.

Unlike most kitchen design books, “Kitchen Think” is a woodworker’s guide to designing and furnishing the kitchen, from a down-to-the-studs renovation to refacing existing cabinets. And Nancy shows you how it can be done without spending a fortune or adding significantly to your local landfill.

Whether you’re planning a kitchen for a newly built house or remodeling an existing kitchen, there are some basic steps to getting started. The first step is to break what may feel like an overwhelming task into manageable components.

Here are a few examples of kitchen remodeling scenarios:

- Gut the kitchen. Whether you’re gutting the space to beef up structural elements, enhance insulation or simply to get the ceiling, walls and floor level, flat and plumb, a hardcore gut usually entails new cabinets. This doesn’t necessarily mean cabinets that are newly built; some complete remodels incorporate salvaged cabinets, modified to work in their new space. But the idea here is that you’re starting from scratch.

- Partial remodel: Keep the best of what you have and add to it. This scenario encompasses kitchens that have a few original cabinets that are charming and perfectly fit the character of the house, but there are too few of them (or they have impractical counters, or they need to be refinished and have various parts tuned up etc.).

- Refacing existing cabinets in cases where the existing cabinets are in good shape and were well made, but you want to change the aesthetic of the kitchen.

- Modify existing cabinets to make them more functional, as when old drawers were poorly made and slid on wooden runners, and you decide to replace them with newly made drawers that are easy to clean and mounted on full-extension slides.

Assess the Situation

Think about how you use the kitchen and what you would like to change. Do you live alone, or are you the only one who cooks? Do you work with someone else in the kitchen – i.e. do you need space for more than one cook? Your answers will have a bearing on considerations such as the space you need between cabinets or appliances and central features such as tables or islands.

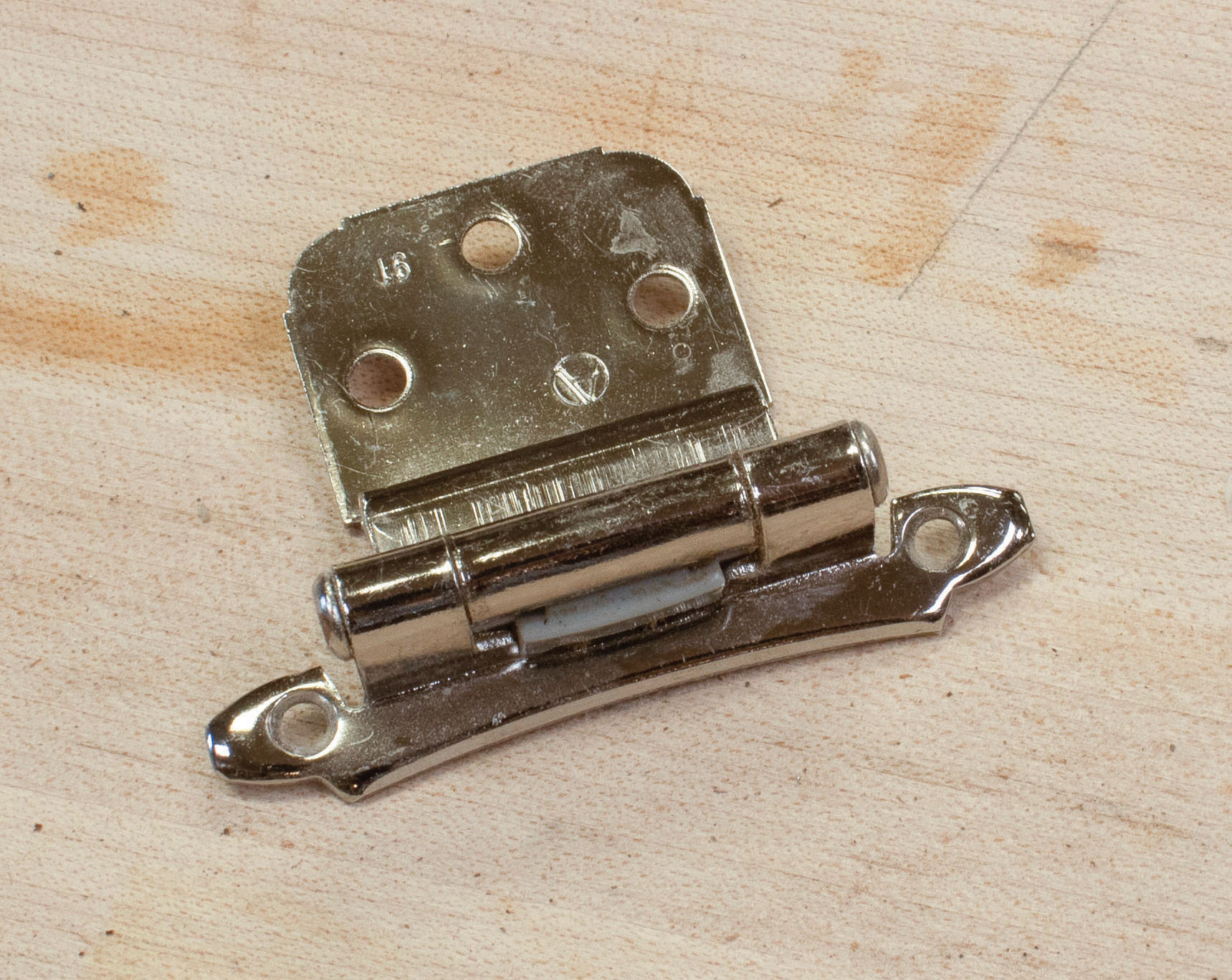

Do you have children in your kitchen, whether they live with you or visit often? If so, think about how you can avoid creating sharp corners, especially those at children’s eye level. Also choose hardware without tight spring closures that can hurt little fingers, and plan to keep poison or alcohol out of reach.

Do you really cook or do you just want a nice-looking kitchen? How much do you really want to spend on appliances and fixtures marketed as “professional” or “high performance?”

Now list the best features of your existing space. These may include:

- Proportions and shape of the room

- Natural light from windows or skylights

- The view through windows

- Existing cabinetry, counters or other elements, such as a lovely old wooden floor.

Make a wish-list of elements you’d like to add.

Now list the things you consider detractions. Examples may include:

- The room is dark

- There’s no window over the sink (nor is adding one an option)

- The room feels cold

- The room is tiny and has too many doorways

Next note any constraints imposed by the existing space. While some may be able to be changed, time and budget permitting, others may not be. Instead of viewing what you can’t change as an obstacle, think of how it could be an opportunity with the benefit of some creative thinking. For example, if your kitchen is tiny, as architect Christine Matheu’s was (see pages 342-345), take note of that – then think about whether there are ways to make it feel lighter and more spacious. In Christine’s case, the answer was to add new skylights, enlarge the window on the exterior wall and install a large window on an interior wall that overlooks the entryway to her house. But the ultimate genius move by Christine was to open up one portion of the wall between the kitchen and dining room to create a space for the cook to converse with family and friends while preserving a clear distinction between the work and public spaces.

The goal of this exercise is to begin defining priorities.

Now move on to looks.

The steps above are general; they make no mention of your kitchen’s aesthetic. Think about how your kitchen looks now and how you want it to look. Do you want it to feel more in sync with other rooms? If so, you may take your design cues from those. But if you’re leaning toward a period style, keep some caveats in mind (see pages 295-301); also, if you want a period kitchen to be convincing, you need to bone up on some kitchen history, bearing in mind that kitchens of yore were not public spaces, but the servants’ domain.

Order of Work

Kitchens are complex rooms with many working parts. For the best job, you should think carefully about how these different parts will go together before you start building. A typical order of work is as follows:

- Demolition.

- If you’ve gutted to the studs, joists and rafters, take this opportunity to add blocking for cabinet installation. Trim or shim framing lumber to make the walls, ceiling and floor flat and level. Insulate exterior walls as appropriate.

- Rough plumbing (sink supplies and drainage, gas for stove) and electrical wiring (lighting, appliances, dishwasher, fridge, stove, undercabinet lighting, switches etc.).

- Patch or replace ceiling, walls and subfloor as necessary. Tape and finish joints.

- Prime and paint at least one coat of color.

- Finish floors (lay tile or sheet flooring; sand wood floor and finish).

- Install cabinets.

- Measure and make templates for counters.

- Fit doors and drawers (if fitting on site).

- Remove doors and drawers for finishing in shop (ditto).

- Install counters.

- Install backsplash or tile.

- Install sink and faucet.

- Replace doors and drawers, install set screws and final hardware.

- Final painting.

- Finish electrical – install the light fixtures, disposal, appliances, switches etc.