The following is excerpted from “To Make as Perfectly as Possible: Roubo on Marquetry,” by André-Jacob Roubo, translated by Donald C. Williams, Michele Pietryka-Pagán and Philippe Lafargue.

The different Compositions of Dyes appropriate for dyeing Woods, and how to use them

The tinting [dyeing or staining] of woods is of great importance for cabinetmakers, because it is with its help that one can give to woods the different colors, which are necessary for representing all sorts of objects, such as fruits, flowers, animals, etc. However, cabinetmakers always make a great secret of the composition of their dyes in order to preserve exclusivity, and not to increase the number of workers in their trade. From that circumstance comes the fact that most of the compositions that the ancient cabinetmakers used have not been passed on to us, or are presently badly imitated. Those being used presently are defective, or even if they are good, cannot be perfected given that those who possess them hide the process. They keep this information secret not only from their colleagues but even from those for whom the theory could be useful in perfecting the composition of their dyes. This would be much more advantageous than the enjoyment of maintaining a secret, which is not a big thing, but which, even when it is perfectly well known to us, leaves us still to regret the loss of the method of Jean de Veronne, who tinted woods with boiling dyes and oils that penetrated them. This would be a very helpful thing to know, the research of which would be a worthy undertaking for some of our scholars. It is highly wished that one could find the means to use the chemicals having a good tint in the dyeing of woods, because their colors would be more durable. Sadly, the colored parts of most of these chemicals are too thick to penetrate the interior of woods, which is absolutely necessary, so that when working with tinted woods they are all found to be of uniform color throughout their entire thickness and the surface.

That is why in the description of the woods, without the means to which I would like to know the procedure to accomplish the perfect tint, I will explain only ordinary procedures to cabinetmakers, to which I will add some of my own experiences, which is still a long ways from attaining the perfection of which this part can be capable.

The five primitive colors are, as I said above, blue, yellow, red, taupe [brown] and black. Each of these colors is given by different chemicals, which, when mixed together, give the second or composite colors.

The blue appropriate for tinting woods is made with indigo, diluted in oil of vitriol [also known as sulfuric acid], and then put in a sufficient quantity of water.

Yellow is made with barberry, yellow earth and saffron mixed together, or even simply from gaude [this plant, Reseda luteola, is known as weld].

Red is made from the boiling of wool, or even a concoction of Brasilwood mixed with alum.

Taupe is made with walnut husk.

Black is made with the wood of the Indies, the gall nuts and iron sulfate.

Before entering into the detail of the composition of different stains, I am going to give a general idea of the chemicals of which they are composed, so that the cabinetmakers may be less subject to being fooled when they buy them.

Indigo is a type of ash of a deep blue, provided by the leaves of a plant that grows in the Americas and Indostan, and which they sell in little pieces. For it to be good, it must be medium-hard, so that it floats on water, so it is inflammable and of a beautiful blue or deep violet color. Its interior should be strewn with little silver-colored spangles, and appear reddish when rubbed with a fingernail. Indigo is preferred over all other chemicals for staining woods because it is a powder of extremely fine and granular pieces, which are easily introduced into the pores of the woods.

Oil of vitriol or sulfuric acid is the final spirit that one gets from vitriol. This acidic liquor should be very concentrated and be absolutely free of all aqueous parts to be of a beautiful blue color, as I will speak more of later.

Barberry is a little bush of which the fruits, and the bark of the roots are stained in yellow. That from Candie [island off the coast of Crete] has a very yellow wood, and passes for the best.

Woad [this cannot be woad that produces a blue dye] is a rather common plant in France. One boils it in water to extract a yellow liquid, which mixed with a bit of alum, tints very well. Dyers prefer that one, which is the most spare [meaning thinnest] and of a rosy color.

One also dyes in yellow with the yellow wood of which I spoke above page 777. Yellow earth is nothing other than yellow ochre, used by painters.

Saffron is a plant that grows in France, especially in Gatinois [western part of France]. It is the pistil of the saffron flower, which gives these little reddish filaments, or better said, orange, which they sell under the name of saffron, which gives a dye of a golden yellow. For saffron to be good, it should be fresh, of a pungent odor, of a brilliant color and when touched it should seem oily and should stick to the hands.

Alum is a fossil salt and mineral, which is used much in dyeing, whether to set up the materials to be stained or whether for fixing the colors [as a mordant], which it retains all the particles by its astrin-gent quality. The best is that of Rome, which is white in color, and is transparent, a bit like crystal.

Liquor decanted from boiled wool is sold by the wool merchants. In boiling this wool, one gets a decoction of the color rose, which is more or less deep, according to how much water is used to scour the wool, proportional with its quantity.

I spoke up above of Brasilwood, page 771. I will content myself to say here that the decoction of this wood gives off a clear red color, tending toward the orange, and that one deepens its color by adding a bit of alum. Brasilwood from Fernambouc is the best, and they sell it all chopped up at the spice merchants, who sell it by the pound.

The husk of walnuts is nothing more than the first wrapping of these nuts, which one takes off before they are perfectly mature, and which one boils in water to extract a brownish or taupey tint.

Indian Wood, of which I spoke on page 777, gives off a concoction of a deep red, which one stains in black, and when one mixes with alum it stains in violet.

Nut gall is a type of excretion that is found on the tender shoots of a type of oak named “Rouvre.” The most highly esteemed nut gall comes from the Levant [the name given to the countries on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean]. The best ones are those that are the heaviest, and where the surface is thorny. There are both green and black ones, both of which work equally to stain in black.

Ferrous sulfate is a type of vitriol that is found in copper mines. It is the most powerful of the acids, it corrodes iron and copper, and it etches the soft parts with an infinite number of small holes, into which the dye is introduced. Ferrous sulfate is also named Roman vitriol or English vitriol, according to whether it comes from one or the other countries. We make some in France that is, they say, as good as the others. The color of ferrous sulfate [known also as green vitriol] is of a light green: it should be neat and shiny.

Verdigris also works well as a wood dye. It is the green rust scraped from copper sheets. For it to be good, it should be dry, pure, of a deep green and filled with white spots.

There you have a bit of a description of the ingredients commonly used for staining/dyeing woods.

All that remains is to give the manner of making use of them.

The Way of Staining Wood Blue

The preparation of blue with indigo and oil of vitriol [sulfuric acid] is done in two ways, namely, hot and cold. Blue for wood is prepared cold in the following manner:

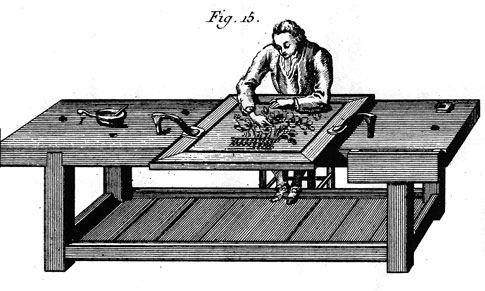

you take 4 ounces of oil of vitriol of the best quality, that is to say, that it is deprived of all aqueous parts, which you pour into a pint-size bottle, with 1 ounce of indigo reduced to a very fine powder. Then you fill the bottle with water, at least nearly so, and you bottle it very carefully, and you seal the cork with wax. you let it infuse for five to six weeks, at the end of which you can use this stain that will be more or less strong, by putting in as much water as you judge appropriate, always ob-serving to add a bit of oil of vitriol, so the dye will be fixed better. When the dye is to the degree of strength that you need, you put it in a stoneware or glazed earthenware vessel, and you soak the wood in it until it is totally penetrated, which sometimes requires 15 days and even one month of time, according to the hardness and thickness of the wood. The wood can hardly have a thickness of more than one line [1/12″].

Cabinetmakers ordinarily use a stoneware butter pot for putting the wood into the dye, which is very convenient because the shape of this vase enables one to put in rather large pieces, without the need of having a very great quantity of dye.

It is very easy to know when the interior of the wood is penetrated, given that you only have to cut a small piece of the wood about 2 to 3 lines from its end. When the pieces that you want to dye cannot be cut like this, you put with them another piece of the same quality, with which you test the degree of penetration of the other pieces.

The Way of Dyeing in Yellow

Cabinetmakers tint in yellow with barberry, with yellow earth and with saffron, which they boil together. This being done, they soak the wood pieces until they are totally stained. The proportion of these chemicals is 2 liters [in this case the French word refers to “litron,” which is about 79 percent of a modern liter, so 2 modern liters is a much larger quantity] of barberry, 6 “sols” [a French penny] of yellow earth, and 4 “sols” of saffron.

A concoction of woad gives a very beautiful yellow of a good tint, and you soak the wood as normal. When this concoction is added to a bit of verdigris, you have a sulfurous yellow color. Saffron infused in grain alcohol gives a very beautiful golden yellow.

The Way to Dye in Red

Red is normally made with brasilwood, which one boils with 6 sols of alum for each pound of wood. This red is a false tint because it is more orange than red. you can substitute the boiling-liqueur from wool, which gives a very beautiful red, leaning toward rose, which one makes deeper by passing the pieces that you have stained into the liqueur of the mixture of Brasilwood mixed with alum. This makes a very beautiful red, more or less deep, depending on whether you leave the pieces of wood more or less a long time in the dye bath of Brasilwood.

Dyeing with decanting liqueur is done very easily. One only needs to boil some wool dyed to this effect, just until it makes a beautiful red concoction. Avoid boiling too much, because the wool will take back the color that it discharged at first.

The proportion of the liquor of wool to be decanted is 1 pound to 4 pints of water for the first decanting, to which one can add a second, even a third, until the wool renders no more color. The concoction of Brasilwood without alum gives a yellowish red, which is sometimes attractive, and is named “Capucine.”

The concoction of Indian Wood is very red, but it makes a blackish stain, which makes a very beautiful violet when mixed with alum from Rome, as I will speak of it later.

How to Dye Taupe [Brown], Black and Grey

Taupe dye is made with a concoction of walnut husk, which can be more or less strong, as you judge appropriate, always adding to it a bit of alum.

An attractive black is made by staining the wood first in a concoction of wood of India (or Campeachy, which is the same thing). When this first application is dry, you dip the wood in a concoction of gall nut in which you have put some ferrous sulfate, or vitriol of Rome. Sometimes one only makes a single dye of these various ingredients, of which the proportion should be 1 part nut gall, 1 part vitriol and 6 parts of Campeachy, all boiled together, into which you dip the wood until it is penetrated.

A grey tint is made with a concoction of nut gall, into which you dissolve some green vitriol [ferrous sulfate] in smaller quantity than for the black stain. The more ferrous sulfate-cuprous there is, the deeper grey it will be. The normal proportion is one part of ferrous sulfate for two parts of nut gall.

The Way to Tint Composite Colors

The ordinary green stain of cabinetmakers is made with the same ingredients as for the blue, to which is added the barberry in more or less quantity, according to whether the green should be more or less deep.

One can make a very beautiful apple green in staining first the wood in ordinary blue, and then dipping it in a concoction of woad, and that with more or less time according to whether one wants to have a green more or less strong.

Violet is made with a concoction of Campeachy, to which one has mixed some alum from Rome. One can have violet more or less deep by staining first the woods in rose and then in the blue, which will give a clear violet.

If, on the contrary, one wishes to have a brown-red leaning toward violet, one stains the wood first in the concoction of Brasilwood, then in that of the Campeachy.

One can obtain composite dye of all nuances imaginable by tinting the wood in a primary color then in another one more or less dark, so that the stain that results from these two colors reflects more or less of each other. This is very possible to do because one is the master to strengthen or weaken the primary colors as one judges appropriate, whether by reason of what the form of the object re-quires, or even by reason of the different quality of wood, which takes the dye more or less well, or strengthens or weakens the color. This has to be highly considered, and it requires much attention and experience on the part of cabinetmakers.

In general, all the dyes of which I just spoke are applied in cold baths. It is not that many of them cannot be used hot, but it is that because it takes a considerable amount of time for the same dye to penetrate into the interior of wood, it is not possible to use them hot. What’s more, cold dyed wood has much more vibrancy than when used with a hot bath.

There it is, a bit of the details of staining [dyeing] wood, at least those that most cabinetmakers use, or which I myself have employed in the attempts that I have made. These have succeeded rather well, but they have not been followed by a long enough time to be assured of the success of my at-tempts. It would be highly wished that those who are currently making use of these dyes, or who will be using them later, apply themselves to perfect them which, I believe, is not absolutely impossible. Having done this, they would be rather good citizens to not make a mystery of their discoveries, but only succeed by rendering them public.

Cabinetmakers dye not only their woods for veneer to use them in the place of the natural color of the woods. They also use these same dyes to accentuate various parts of their works while they are being worked. As such, these dyes, like the red of Brasilwood, the violet of the Campeachy, the black, etc., are used hot, which is very easy to do because it is sufficient for only the exterior of the woods being dyed. Other than these dyes, woodworkers in furniture sometimes use a type of yellow color for bedsteads, which is composed of yellow ochre and common varnish, or of this same ochre and the very clear English glue, sometimes they even put it in only water, which is of little use.

Before finishing the dyeing of wood, I believe I ought to give a least-costly method of dyeing white wood red, which is done in the following manner:

you take some horse dung, which you put in a bucket of which the bottom is pierced with many holes, and you place it above another bucket, into which falls the water from the dung, as it gradually rots. When it does not rot fast enough, you water it from time to time with some horse urine, which helps a lot and at the same time gives a red water, which not only stains the surface of the wood, but penetrates the interior 3 to 4 lines deep. In staining the wood with this dye, one must take care that all the pieces be of the same species, and about equal in density if one wishes that they be of equal color throughout. This observation is general for all water-based stains, which have no palpable thickness nor even appearance [they leave no residue or any evident change in appearance], which requires the cabinetmaker to make a choice of wood of equal color and a density as I mentioned before. This demands a lot of experience and attention on the part of the cabinetmakers. And with the exception of the way to compose and use dyes, it is hardly possible to give theoretical rules on this part, for which success is not often due to anything but experience, which is not acquired except with a lot of time, attention and work.