Here locally, I get asked the following question a lot: How do you stay in business?

It’s a good question. When I explain Lost Art Press to Covington, Ky., city and business officials, they look at me like John and I must have some sort of trust fund that supports our chicanery. But nothing could be further from the truth.

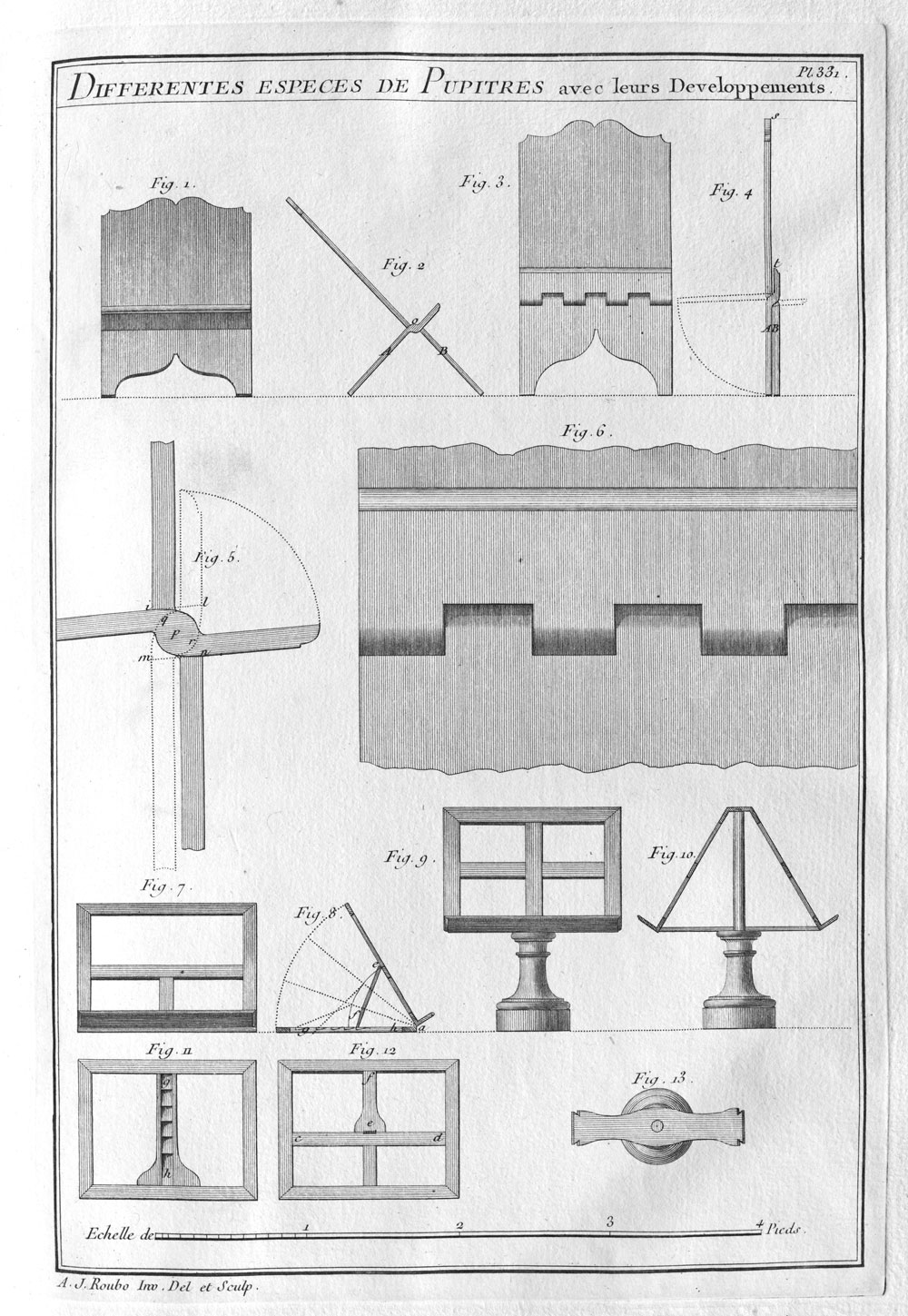

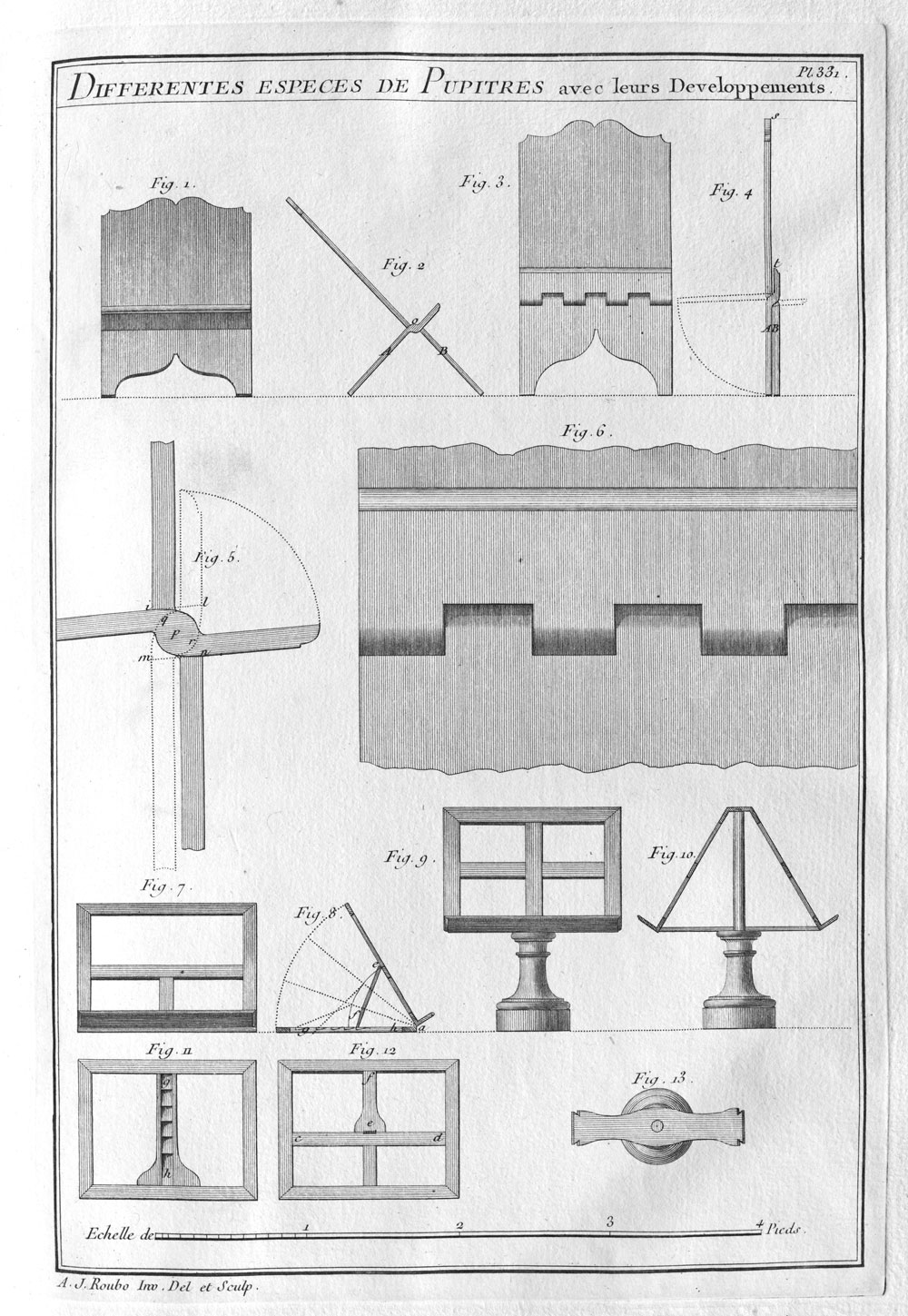

The translation of “l’art du Menuisier” is a good case in point. The project began entirely outside of our grasp. In 2005, I was building French workbenches and trying to translate sections of A.-J. Roubo’s “l’art du Menuisier” for my own use or to publish on my blog.

Then the phone rang. It was Don Williams. He said that he and some friends were working on a translation, too. He asked me how far along we were. The answer: About 10 pages out of 1,200 or so. He said they were further along. So I said: Fine. You win.

During that phone call we agreed to work together to translate the 18th-century books that we were both obsessed with. We thought it would take a few years of work. We were incredibly wrong. It’s now 2017. We are much older and finally on the cusp of publishing “With All the Precision Possible: Roubo on Furniture,” the book I’ve dreamed about for years.

Unfortunately, it’s an expensive book – $57 is a lot of money.

Unfortunately, it’s an expensive book – $57 is a lot of money.

When you set the price for a book you need to accommodate the price of printing the physical book. (And when you print it in the United States instead of China, that price is about four times the China price.) Then you have to sum up the hours that everyone spent on the book and assign some cost to that work.

For this book, I refused to calculate the price of the writing, translating and editing labor. Why? Simple. We would have done it even if we hadn’t been paid.

Everyone in this translation project, from Don Williams down to the editor, designer and copy editors believe that this is something that should be available to anyone who wants to become a woodworker. It’s not some piece of obscura – this book is the foundation of the legal aspects of what is quality woodwork in most countries.

And there has never been an English translation published.

So when I calculated the price of “Roubo on Furniture,” I discarded the cost of our labor. I flushed it, really. So the price is based solely on our costs to print it and bring it to market.

I know that $57 is a lot of money for some wood pulp bound in cotton cloth, fiber tape and glue. But know that if you buy “Roubo on Furniture,” you are buying hundreds – maybe thousands – of hours of unpaid work for the love of the craft.

Or don’t.

In the end, we really don’t care. Everyone involved in this project – Don, Michele, Philippe, Wesley, John, Megan, Suzo, Kara and many others – are happy either way. We’ve done what we set out to do many years ago. We have all absorbed the incredible woodworking knowledge Roubo recorded. We’ve packaged it in a gorgeous book we can refer to whenever we please.

And we now offer it to you.

— Christopher Schwarz

Like this:

Like Loading...

“Roubo on Furniture” will forever be known as one of our children that had a difficult birth. The cover cloth we ordered for the book has been discontinued. As was our backup color.

“Roubo on Furniture” will forever be known as one of our children that had a difficult birth. The cover cloth we ordered for the book has been discontinued. As was our backup color.

Unfortunately, it’s an expensive book – $57 is a lot of money.

Unfortunately, it’s an expensive book – $57 is a lot of money. With the impending release of the standard edition of “

With the impending release of the standard edition of “