This is an excerpt from “The Intelligent Hand” by David Binnington Savage.

It began with a walnut desk that had been commissioned by a London architect friend. This was a prestige job for a building conversion in London’s Covent Garden. It was right on the Piazza – a prime spot. My desk was to fit diagonally across the reception area. Malcolm and I worked and worked to get this spot-on. Table delivered, everyone delighted, craftsmen paid.

A few weeks later I get a call: “The building has been sold. The new owners don’t want your table, so it has been taken by the managing director of the developing company for his Dorset house. We suggest you get in touch with Derek’s wife, Mary.”

WHAAAAT!!!!…. I hated this. Malcolm and I had made this table for a specific place in the centre of London. Now it was going into some rich dude’s country house – a disaster I sulked over for days. It turned into something unexpected.

Getting hold of Mary Parkes was not easy, and I didn’t really want to do it. Making the phone call took me ages. When I did talk to her it was, “Oh I love your table! We are restoring a house in Dorset and we have put it there. We need some special dining furniture. Can you help us?”

I remember feeling extremely scared before I met Mary. I went trembling to a very smart address just off the Kings Road in West London. I came with some draft ideas of chairs and tables. Derek arrived later; he was genial and friendly and very much the worse for a few drinks. We settled nothing but agreed to meet at their Dorset house sometime later.

When we met again, Derek was on great form. He spent a whole morning showing me around a wonderful old house. He proudly showed me some of the restoration work. It was incredibly expensive but almost invisible. Derek took great pride and pleasure in what he was able to do to restore that beautiful old house. He introduced me to the gardeners and household staff; he knew each by name and knew about their families and children. This man was operating socially on a completely different plane to the rest of us. To me, he was amazing; I was bowled over. He liked making things, and enabling things to be made.

Mary and I worked on her ideas. Derek wanted chairs in which he “could have a great dinner party, consume a bottle of claret and not damage himself falling out of the chair.” I remember Mary doing sketches of chair backs that I recognised from chairs in the Doge’s Palace in Venice. I picked that up and developed it.

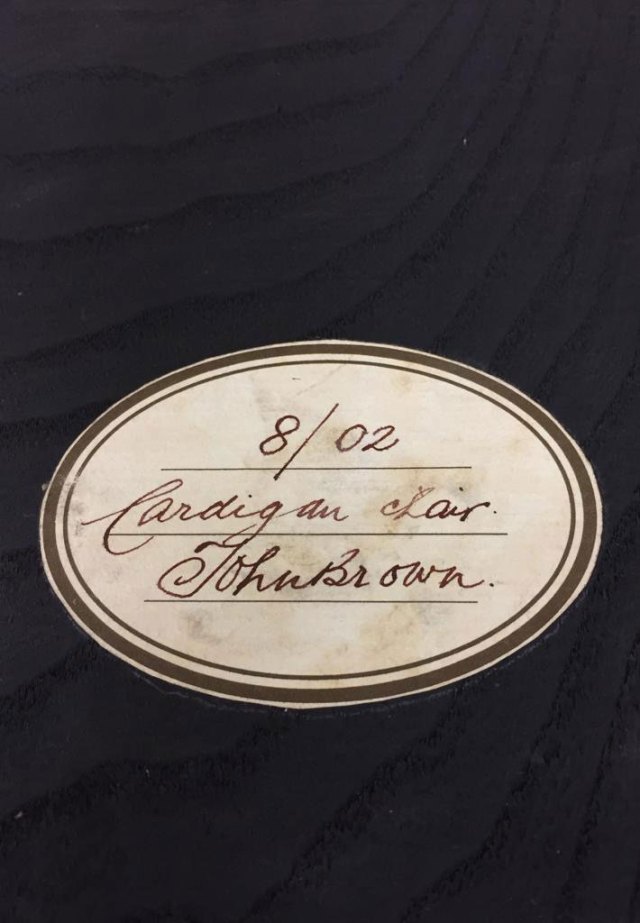

We made a table in solid English cherry and a set of chairs. It was the biggest job I had ever done. I remember Malcolm and Neil sweating blood over it. Mary wanted holly and dyed blue veneer details to match her fabrics.

“We can do that,” I said with complete conviction and total ignorance. We would find a way.

We delivered the pieces, the bill was paid and the client was happy. I brought over my photographer, John Gollop, to take a shot of the pieces in location. John did that, then did something that was to me extraordinary. He picked up a chair, carried it into the next room and put it in front of a full-length window. There was a huge potted plant behind it. The photo he took changed everything.

Derek and Mary were happy if I made versions of their chairs. I thought I might make two or three. John’s photo and versions of it were in every glossy magazine for what seemed like months – the 1980s equivalent of going viral. It was an early confirmation of what furniture maker Garry Knox Bennett much later told me: “Dave, we are all in a giant photographic competition.”

We were making these damn chairs in various timbers for clients all over the country for the next few years. But more important, it told me that I could do this: I could talk with people, nice people, such as Mary and Derek Parkes, and come back with ideas for furniture that would make their homes better places to live. I could listen to what they wanted and translate that into an image that fitted them like a good suit of clothes.

Thankfully, I was a good listener; the stammer had taught me that. The first quality of a designer is to be a good listener, to take the brief and hear what is not always said. Then take the idea back to the workshop and make it. The making would be done without compromise; we would make as well as we could. Mary and Derek hadn’t quibbled over price; they wanted something special – something like the house they were living in, something new but worthy of the place. IKEA wouldn’t quite work here. The idea of “designing for clients” came directly from this job.

When I met Derek again nearly 30 years later, he was still at Blackdown House. His life has become a tribute to a wonderful English country house. We made another piece for the same room. I love that – do the job well enough and you will be working for a small group of clients for 40 years. They will always want you to make another piece.

— Meghan B.

Like this:

Like Loading...