Tune-up your think melons and caption this painting.

The painting is 17th-century and by an unknown Italian artist. The companion painting featured unclad blacksmiths.

–Suzanne Ellison

Tune-up your think melons and caption this painting.

The painting is 17th-century and by an unknown Italian artist. The companion painting featured unclad blacksmiths.

–Suzanne Ellison

While Katy’s soft wax is great for furniture surfaces – especially interiors – she has a new devoted customer: Crucible Tool. Unbeknownst to me, Raney and John have been using the soft wax on our improved-pattern dividers as the final finishing step.

In fact, Raney asked me to make a big batch for him so we didn’t waste so many little 4 oz. tins.

If you’d like to give soft wax a try, Katy has a batch in her etsy store that is ready for shipment. The wax is $12 per 4 oz. tin. I use it on drawers, turnings, chairs and even as a final topcoat on oil finishes.

— Christopher Schwarz

P.S. We hope to have a new black soft wax soon. Oh, and about the photo of the cat: The wax had nothing to do with the hair loss.

One of the ideas that’s been crashing around in my head for years is that vernacular furniture – what I call the “furniture of necessity” – is divorced, separate and independent from the high styles of furniture that crowd the books in my office.

This idea is not commonly held.

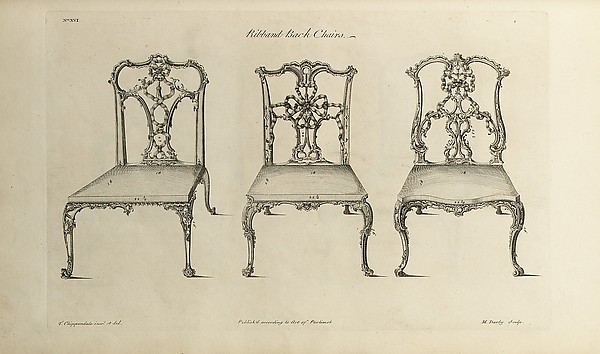

The conventional wisdom is this: Chippenton Sheradale invents a style of furniture that is Neo-Classical Chinese. So he publishes a pattern book to illustrate his new pieces, and the style becomes all the rage. All of the rich people want pieces in Neo-Classical Chinese to replace all the pieces in their houses that were Neo-Chinese Classical.

So the local cabinetmakers oblige and (as a result) can all afford new chrome rims for their carriages.

Rich rural farmers see the pieces in the new style and return home with the crazy idea that they should also have pieces in the latest Neo-Classical Chinese style. So they get Festus, the local cabinetmaker, to build them a Neo-Classical Chinese chair. But Festus uses Redneck Maple (Holdimus beericus) because Festus can’t get New Money Mahogany (Stickusis inbutticus).

Oh, and Festus takes some liberties with the new furniture style to please his rural customers, who want a series of cupholders in the arms that can accommodate a Bigus Gulpus.

Then the poor farmers see the Redneck Maple Neo-Classical Chairs owned by the rich farmers and ask their local carpenters to make copies, who also make changes to the design (a gun rack on the back). And then the dirt farmers see that chair. And so on.

Meanwhile, back in the city, a furniture designer draws up a pattern book for Neo-Gothic Romanian furniture. The cycle begins again.

All this sounds plausible because it has been written down in almost every book of furniture history ever published. The rich make something fashionable, and the poor imitate it until the rich become annoyed or bored. So then the rich find a new style, which the poor imitate again.

The only problem with this theory of degenerate furniture forms is that the furniture record doesn’t always go along with the theory.

I think there’s furniture that is divorced from the gentry. Furniture that is divorced from architecture. Instead of beginning with a pattern book, it begins with these questions: What do I need? What materials do I have? What can I make that will take little time to build but will endure (so I don’t have to frickin’ build it again)?

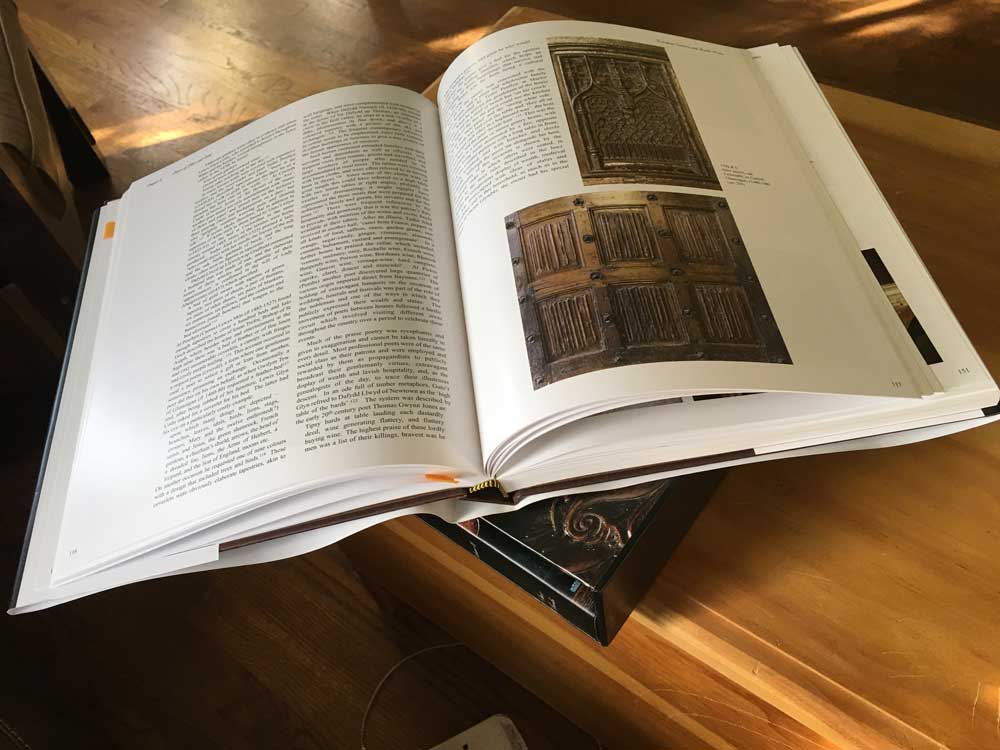

For several months now I have been plowing through “Welsh Furniture 1250-1950” (Saer Books) by Richard Bebb and have been thrilled to find someone who thinks the same way. Bebb has done the research on the matter when it comes to Welsh furniture. And he has convinced me that I’m not nuts.

In the first section of Vol. I, Bebb deftly eviscerates these ideas like a fishmonger filleting a brook trout. It’s an amazing thing to read. I’ll be writing more about Bebb’s research in future entries, but if you want to get right to the source, I recommend you snag your own copy of this impressive work.

— Christopher Schwarz

In 1559 Richard Dale, a local carpenter, completed an addition to Little Moreton Hall that included a large bay window to light the new dining room. The estate owner was apparently very pleased with the job and allowed Dale to sign his work. Although a bit garish, his signature adds to the history and character of this fine old house.

In combination with construction methods, woods used, a signature and a date we can learn a lot about the maker and the communities in which he or she worked. For the owner, the signature of the maker extends a hand into the future and forms a connection.

Between 1510 and 1530 Robert Daye carved 79 bench ends in the Church of St. Nonna on Bodmin Moor in Altarnun, England.

I think he deserved to make one bench end to commemorate his efforts.

Phillip D. Zimmerman’s article, ‘Early American Furniture Maker’s Marks’ (Chipstone) provides many good examples of signatures and where they have been found (undersides of drawers, the top, etc).

On the back of this high chest both makers signed their work. Top: ‘Made by Josha Morss/Jany 1748/9.’ Bottom: ‘Made by Moses Bayley Newbury February AD 1748/9. Just to make sure they both put two signatures on the chest. They worked in what is now Newburyport, Massachusetts.

In another example the signature at the top of this chest was deciphered as ‘Walter Edge’ in the 1940s. Who was Walter Edge? No telling, because decades later Walter Edge turned out to be ‘Upper Edge’ a shipping mark!

Zimmerman also made note of signatures that provide other details about the maker. Although he didn’t provide a photo (and I couldn’t find one), somewhere out there is a Philadelphia-made table with the following written on the underside: ‘Made by Elias Reed in the year 1831 this table caused me to give Black Eye to a frenchman.’

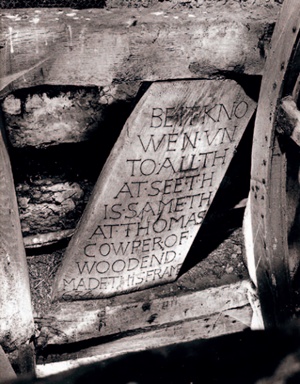

Although he knew few people would see his work, a bell framer left his mark high up in the bell tower of St. Botolph’s Church in Slapton, Northamptonshire.

The tower is too fragile to bear the weight of the two bells it previously held, but the bell frame and its plaque are still there. It reads, ‘Be it knowen unto all that see this same. That Thomas Cowper of Woodend made this frame. 1634.’

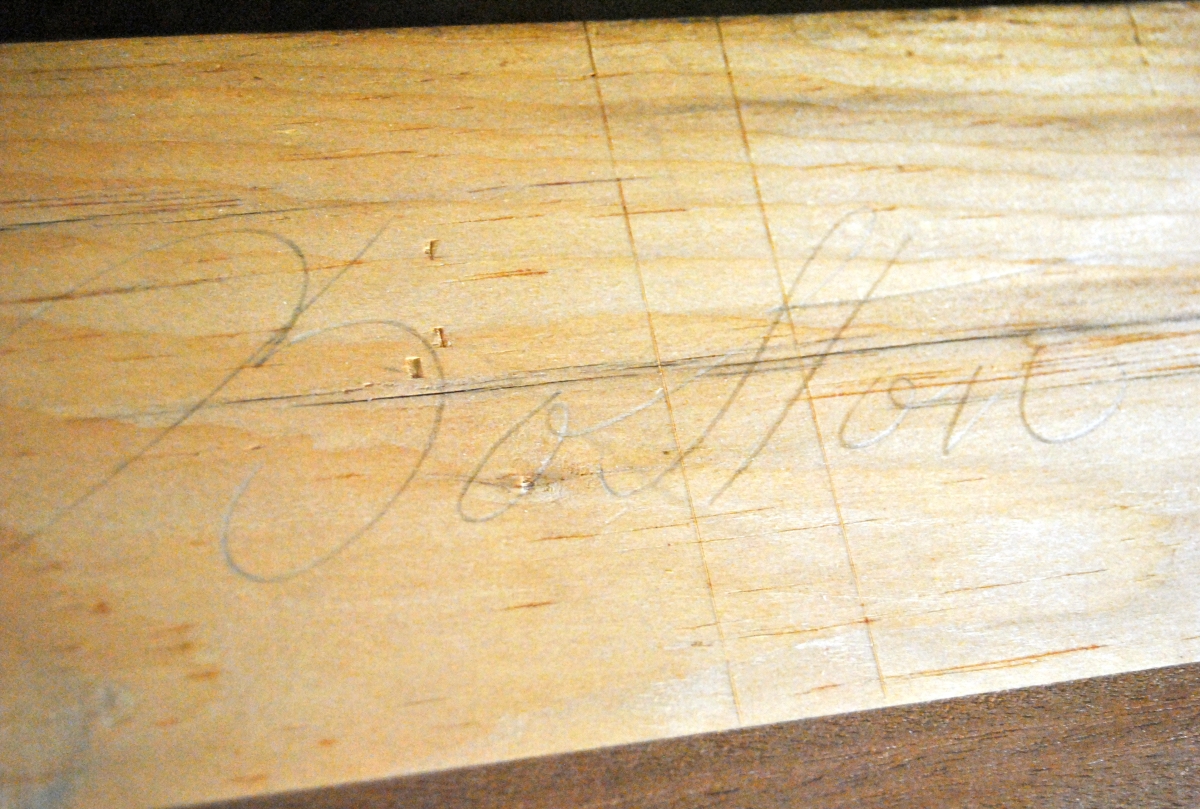

Earlier this year a mahogany bow-front Charleston-made chest was aquired by the Charleston Museum. The chest is from the workshop of the well-known and prolific Robert Walker and is on display at the Joseph Manigault House.

Prior to going to auction the previous owner thought the chest might be a Robert Walker Charleston piece. He disassembled the chest to inspect it and found written on the top support rail under the chest top the following: ‘Boston, October the 18th, 1805.’

Boston was once a slave and freed by 1790 or 1795. Even though the signature was hidden, some articles have termed the act of a 19th-century freed black craftsmen signing his name to something he made as ‘audaciously indiscreet.’ To me, it was a determined affirmation of, ‘I made this’ and also, ‘I exist.’

–Suzanne Ellison

We weren’t happy with the paper thickness of our H.O. Studley posters that went up for sale in May. So we found a new printer that would work with thicker paper. We reprinted the entire run and have sent replacements to everyone who ordered posters through the Lost Art Press website.

Almost everyone should have received their replacement posters by now. If you haven’t, give it until Monday’s mail arrives and then send a message to help@lostartpress.com and we’ll check your order. If you bought one of the posters at Handworks, please send a message to help@lostartpress.com, and we’ll send you a replacement immediately.

The Studley posters now in the store (click here) are printed on the new, thicker paper by a company a few blocks from our storefront in Covington, Ky. The posters are significantly heavier (they were a bit of a struggle to roll to get into tubes) and are still $20, which includes domestic shipping.

— Christopher Schwarz