My next book, “Ingenious Mechanicks: Early Workbenches & Workholding,” is about one-third designed. As with all my books, it is wrestling with me like an alligator in a vat of Crisco.

Suzanne “The Saucy Indexer” Ellison has turned up a number of new images of old workbenches recently that have reinforced and nuanced some of my findings and conclusions about early workbenches.

The image at the top of this blog entry is not one of them.

Suzanne plowed through about 8,000 images (a conservative estimate) for this book. And some of the images were dead ends, red herrings or MacGuffins.

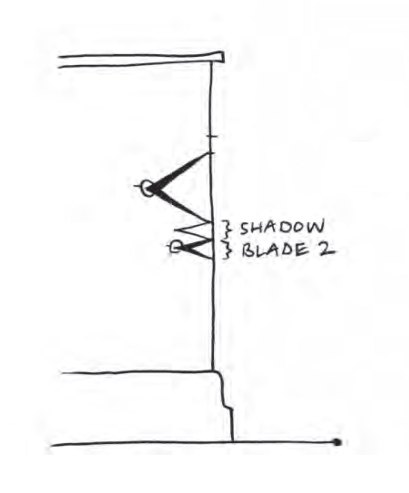

In the image above (sorry about the low quality), we have a bench that is off the charts in the odd-o-meter. It is from Corsica, sometime between 1742-1772, and was painted by Giacomo Grandi, who was born in Milan but lived on Corsica.

Here’s what is strange:

- It is a low workbench with the screw-driven vise perhaps in the end of the bench. Or the benchtop is square. Either way, that’s unusual.

- The screw vise has only one screw and one vise nut.

- The vise’s chop is weird. It is longer than the bench is wide.

- The chop is being used in a manner that simply doesn’t work (I tried it on one of our lows benches). This arrangement offers little holding power.

So instead of saying: “Hey look we found a bench that makes you rethink end vises,” we are instead saying: “Hey I think this bench is the result of the painter trying to create a workbench to assist his composition.”

As I am typing this, Suzanne and I are trying to figure out if we’ve found a tilted workbench from Corsica that is similar to Japanese planing beam. Or if it’s a victim of forced perspective. Or something else.

At times such as this, I can see how a book could fail to be published. There is no end to the research, the new findings or the greasy alligators.

— Christopher Schwarz

So what is “The Afterlife of Trees” about? It’s about stories.

So what is “The Afterlife of Trees” about? It’s about stories.