Do you need a new workbench – perhaps one based on traditional forms? We probably have a resource to help. Below are just a few of our workbench offerings – in video and book form. Plus, a link to video tours of workbenches Chris and others have built in the last 25 years.

Video: “Roubo Workbench: By Hand & Power”

Building a workbench using giant slabs of solid timber is easier than you think. Christopher Schwarz and Will Myers, who have built hundreds of workbenches in their careers, show you how to do it with simple tools and wet wood.

“Roubo Workbench: By Hand & Power” walks you through the construction of an 8′-long slab workbench starting with wet chunks of inexpensive red oak. Will and Chris show you how to tackle each operation using only hand tools, only electric tools or a clever combination of both.

The 4:19-long video also includes copious amounts of workbench design details – including how to scale the height, width and length of the bench for your work – so you can customize your bench for your body. There’s also an extensive discussion of basic workholding – where to put your holdfast holes and how you can work easily without a tail vise.

Video: “The Naked Woodworker”

“The Naked Woodworker” video seeks to answer the simple question: How do you get started in woodworking when you have nothing? No tools. No bench. No skills. And no knowledge of where to begin.

Veteran woodworker and teacher Mike Siemsen helps you take your first steps into the craft without spending a lot of money or spending years setting up shop. In fact, Mike shows you how to acquire a decent set of tools and build a workbench and sawbench for about $600 or $700 – something you can accomplish during a few weekends of work.

“The Naked Woodworker” begins at a Mid-West Tool Collectors Association’s regional meeting with Mike sifting through, evaluating, haggling and buying the tools needed to begin building furniture. Then, at Mike’s Minnesota shop, he fixes up the tools he bought. He rehabs the planes, sharpens the saws and fixes up the braces – all on camera.

On the second video in the set, Mike builds a sawbench and a fully functional workbench using home-center materials. Both the sawbench and workbench are amazingly clever. You don’t need a single machine or power tool to make them. And they work incredibly well.

The bench is based on Peter Nicholson’s early 19th-century design. It is remarkably solid and is perfect for a life of woodworking with hand or power tools.

Book: “The Anarchist’s Workbench”

“The Anarchist’s Workbench” is – on the one hand – a detailed plan for a simple workbench that can be built using construction lumber and basic woodworking tools. But it’s also the story of Christopher Schwarz’s 20-year journey researching, building and refining historical workbenches until there was nothing left to improve.

“The Anarchist’s Workbench” is the third and final book in the “anarchist” series, and it attempts to cut through the immense amount of misinformation about building a proper bench. It helps answer the questions that dog every woodworker: What sort of bench should I build? What wood should I use? What dimensions should it be? And what vises should I attach to it?

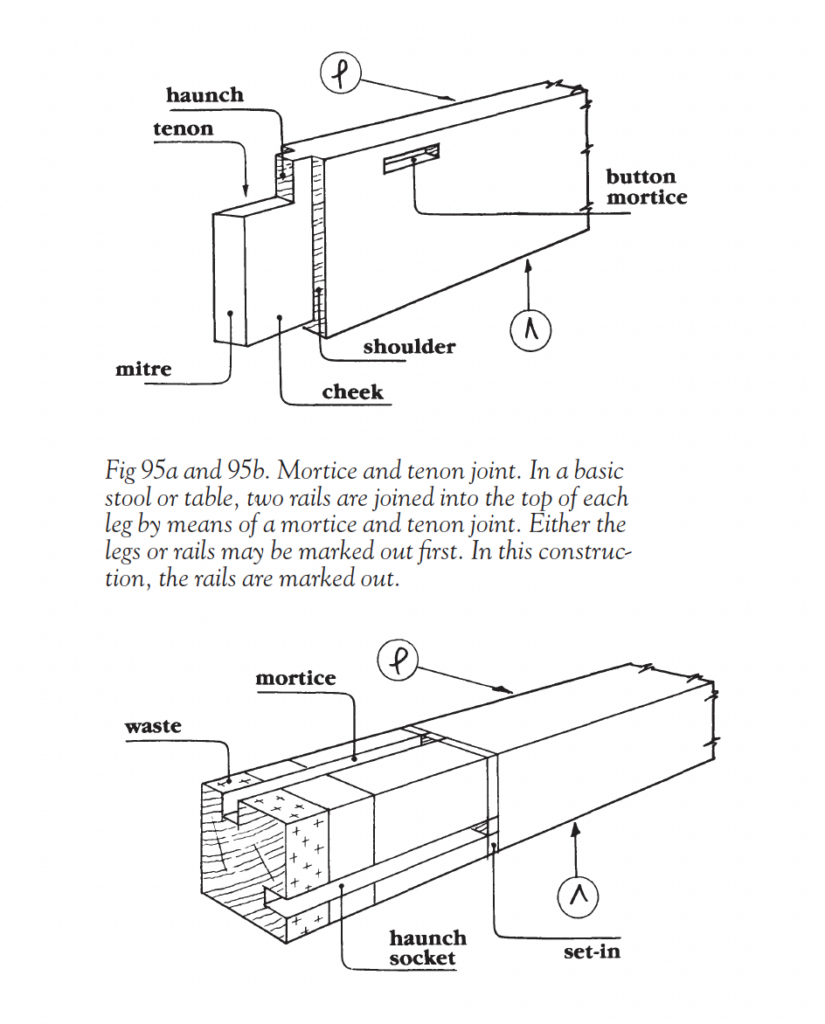

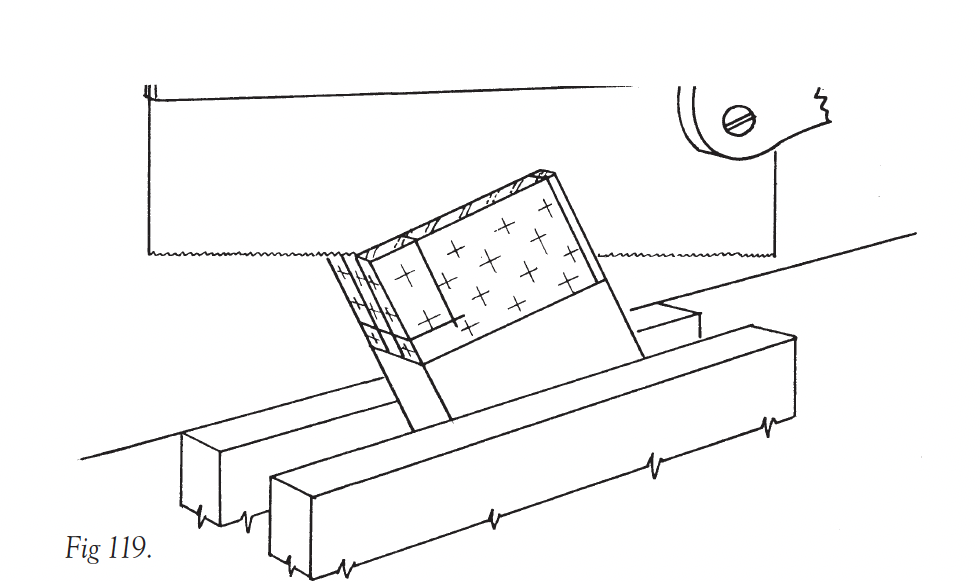

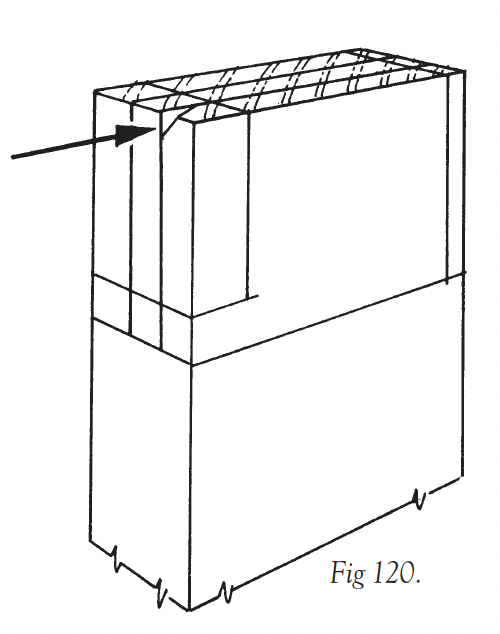

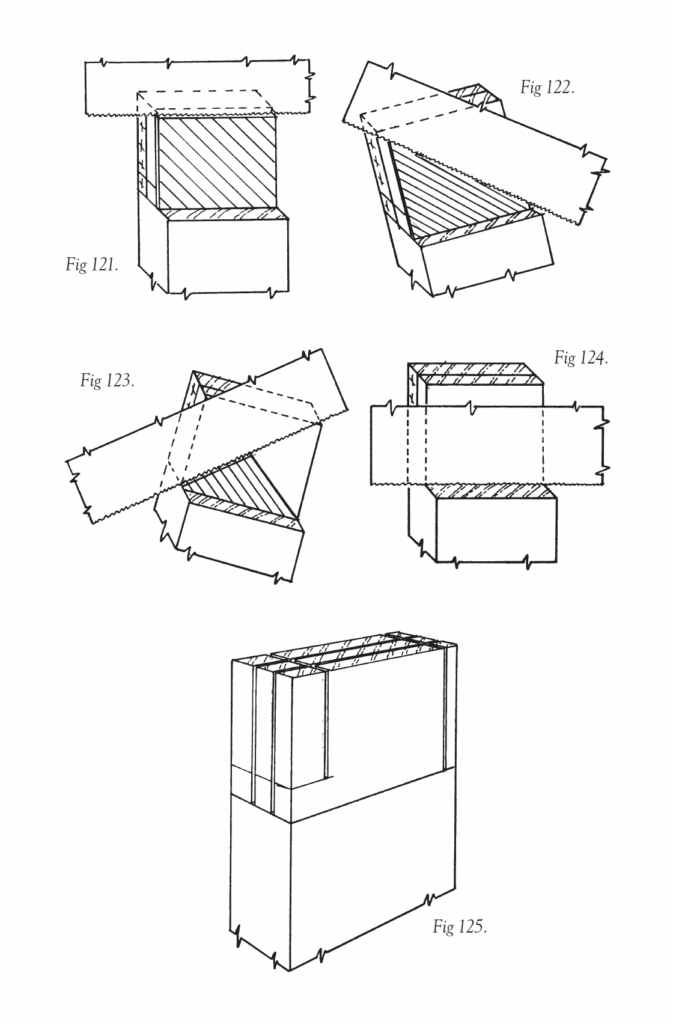

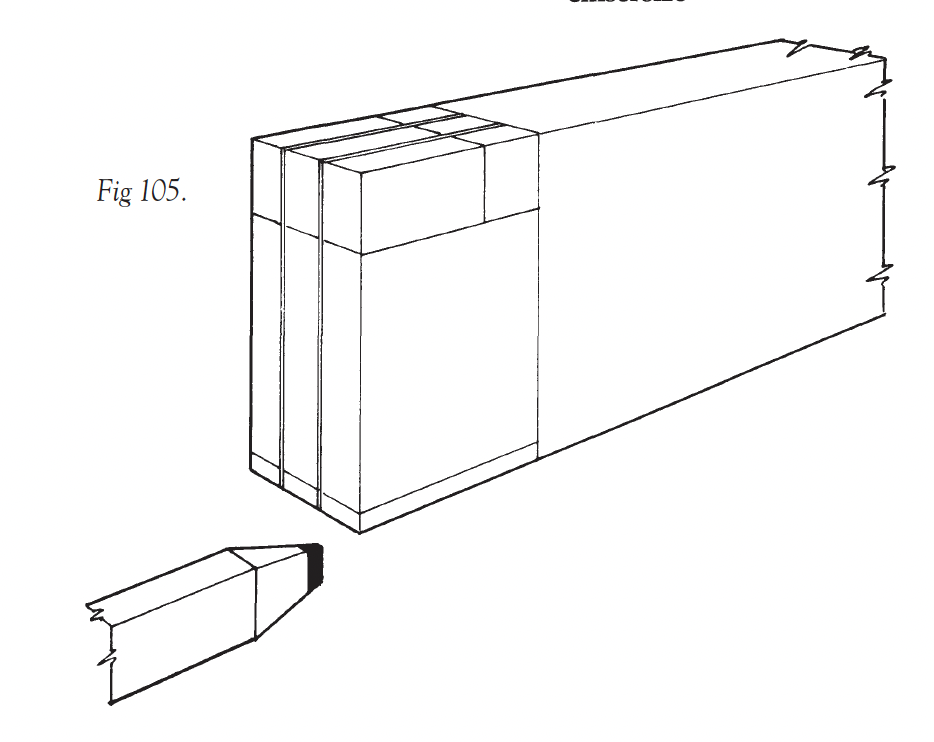

“The Anarchist’s Workbench” also seeks to open your eyes to simpler workbench designs that eschew metal fasteners and instead rely only on the time-tested mortise-and-tenon joint that’s secured with a drawbored peg. The bench plan in the book is based on a European design that spread across the continent in the 1500s. It has only 12 joints, weighs more than 300 pounds and requires less than $300 in lumber. And while the bench is immensely simple, it is a versatile design that you can adapt and change as you grow as a woodworker.

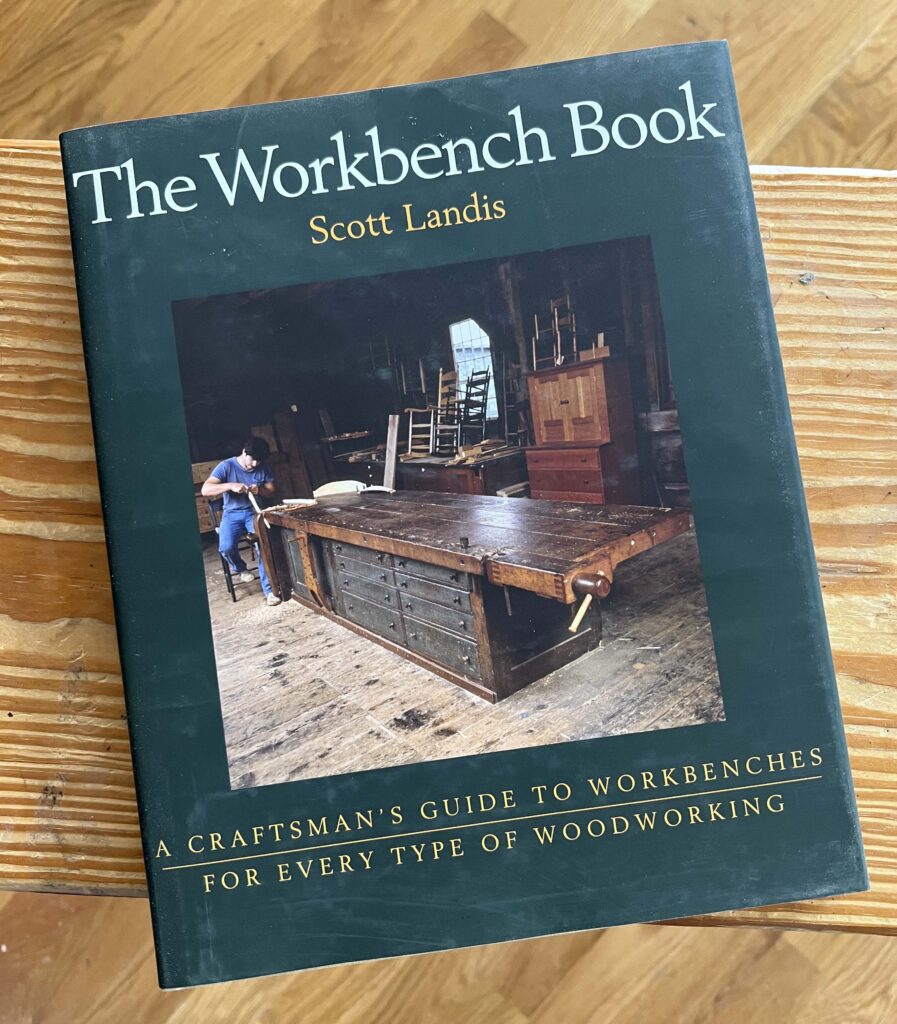

Book: “The Workbench Book”

First published in 1987, “The Workbench Book” by Scott Landis remains the most complete book on the most important tool in the woodworker’s shop.

“The Workbench Book” is a richly illustrated guided tour of the world’s best workbenches — from a traditional Shaker bench to the mass-produced Workmate. Author and workbench builder Scott Landis visited dozens of craftsmen, observing them at work and listening to what they had to say about their benches. The result is an intriguing and illuminating account of each bench’s strengths and weaknesses, within the context of a vibrant woodworking tradition.

This new 248-page hardbound edition from Lost Art Press ensures “The Workbench Book” will be available to future generations of woodworkers. Produced and printed in the United States, this classic text is printed on FSC-certified recycled paper and features a durable sewn binding designed to last generations. The 1987 text remains the same in this edition and includes a foreword by Christopher Schwarz.

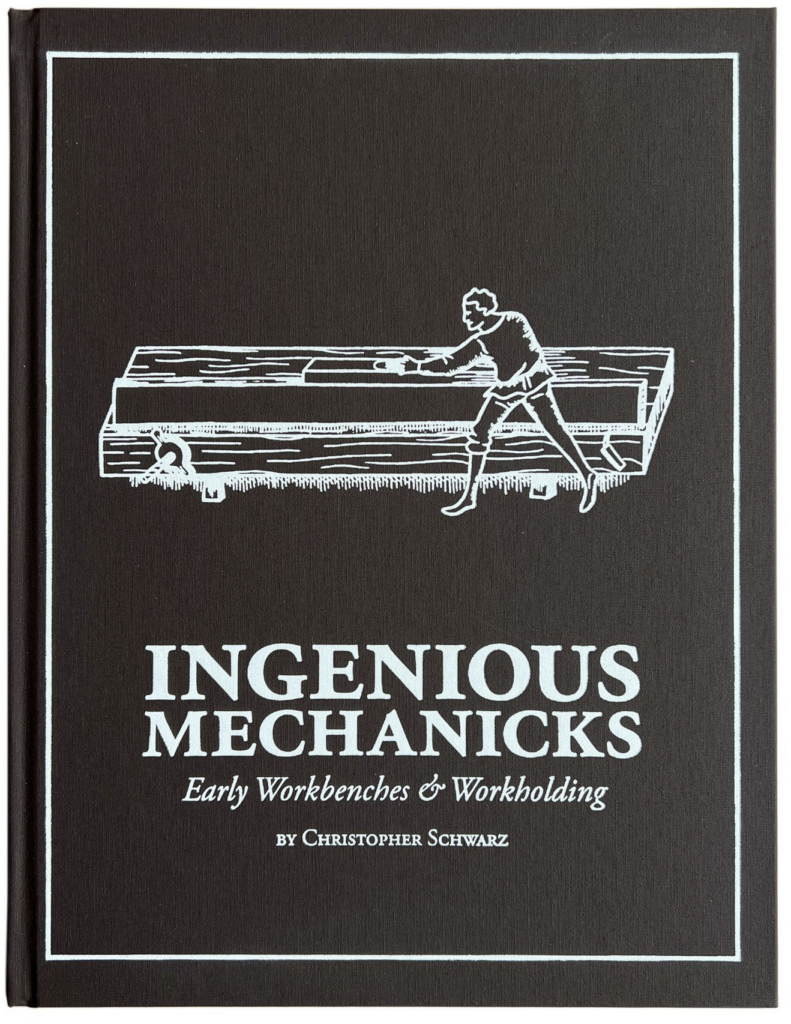

Book: “Ingenious Mechanicks”

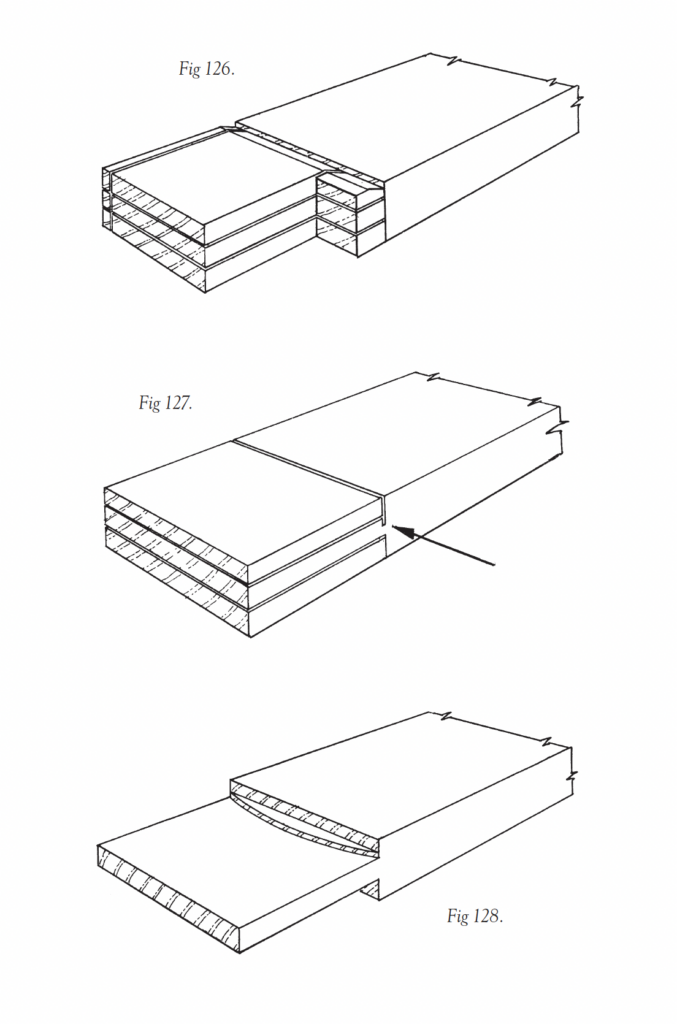

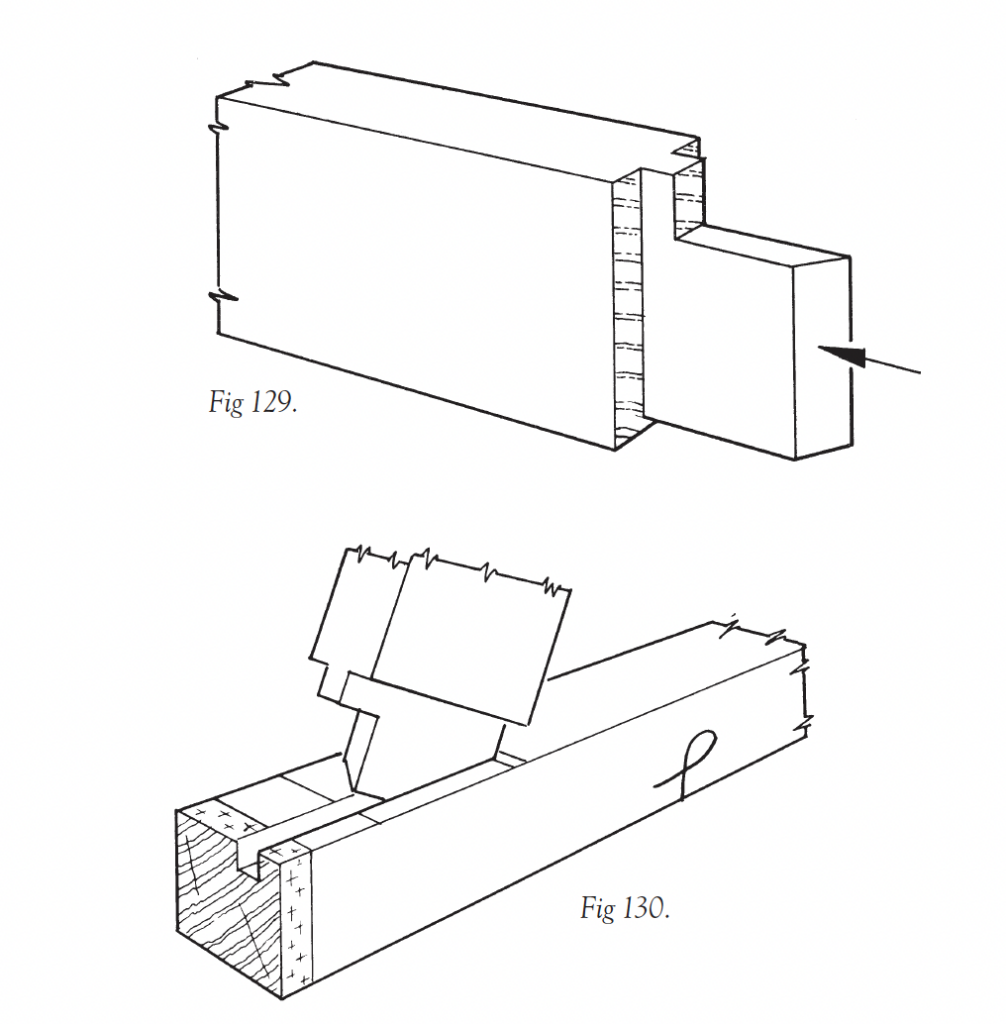

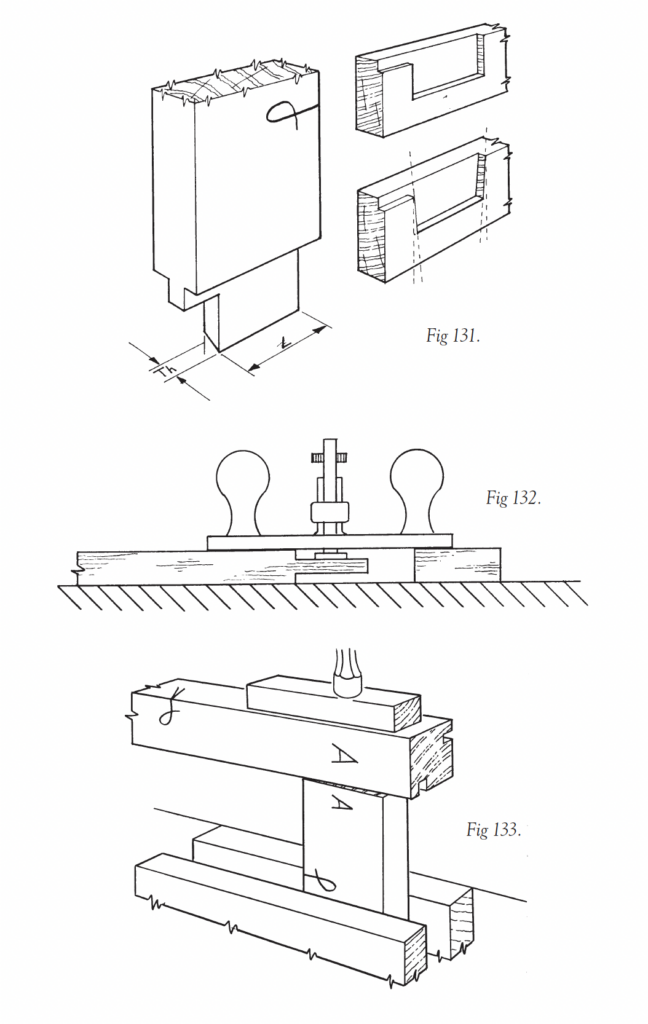

Workbenches with screw-driven vises are a fairly modern invention. For more than 2,000 years, woodworkers built complex and beautiful pieces of furniture using simpler benches that relied on pegs, wedges and the human body to grip the work. While it’s easy to dismiss these ancient benches as obsolete, they are – at most – misunderstood.

Christopher Schwarz has been building these ancient workbenches and putting them to work in his shop to build all manner of furniture. Absent any surviving ancient instruction manuals for these benches, Schwarz relied on hundreds of historical paintings of these benches for clues as to how they worked. Then he replicated the devices and techniques shown in the paintings to see how (or if) they worked.

“Ingenious Mechanicks” is about this journey into the past and takes the reader from Pompeii, which features the oldest image of a Western bench, to a Roman fort in Germany to inspect the oldest surviving workbench and finally to his shop in Kentucky, where he recreated three historical workbenches and dozens of early jigs.

And here are links to video tours of workbench forms that are in the Lost Art Press shop (and three that used to be). (Most of them were built by Chris when he was at Popular Woodworking Magazine.)

The $175 Workbench – now our shipping station when it’s not in use for a class)

The Power Tool Workbench – currently in the Horse Garage – meant to be used during a class by the person not teaching…but it’s almost always covered with wood and other supplies, so we use the low bench in the shop instead).

English Joiner’s Bench – in the shop, behind Chris’ “Anarchist’s Workbench” – it’s a hair taller than the AWB, so it sometimes functions as a stop at the back of his bench. It is the most level spot in our shop – so whomever is working at it during a chair class gets kicked off when it’s time to level legs.

The Cherry Roubo – now at our general contractor’s house. This one – while gorgeous – is just a bit too narrow for efficient and comfortable use during many of our classes, so we gave it to one of its biggest fans. (The size was limited by the width of slabs available at the time of building – had the wood allowed, it could have been wider.)

The Holtzapffel Workbench – in the front window. It’s original twin-screw vise is in the basement; for most classes, the leg vise is more useful. And when I’m teaching a tool chest class, I prefer a Moxon vise atop the bench to raise the work to a comfortable sawing level for more students.

Vintage Ulmia – now with a friend. A good bench – just not great for us.

The Glulam Workbench (aka Gluebo) – now in my basement, for which I’m thankful. I built my other bench, a wee Roubo, to go on the second floor of my old house, and it’s too small for a lot of the house-scale work I’m now doing!

Moravian Workbench – in the front window, back to back with the Holtzapffel. This one was built by our friend Will Myers.

French Oak Roubo – this behemoth is back to bench with my bench.

Lightweight Commercial Bench – Chris bought this one for a Fine Woodworking article on beefing up a wobbly bench. I believe it’s now at his daughter Katherine’s house.

– Fitz