The book is $34 and can be ordered here from our store.

Hayward’s columns cover an enormous swath of woodworking philosophy, from discussions of our insecurities about our skills to the regenerative power of time at the bench. Hayward writes from a unique perspective: He was a traditionally trained woodworker, World War I veteran, professional woodworker, draughtsman, photographer, writer and editor. He steered The Woodworker through World War II (without missing an issue) and was a comforting voice for woodworkers through the most tumultuous portion of the 20th century.

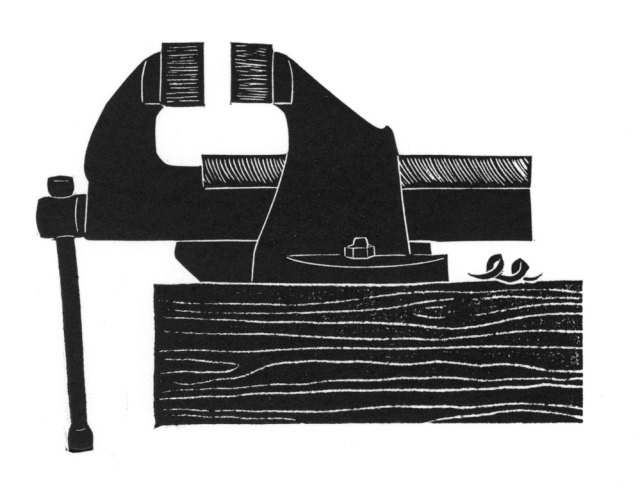

We’ve taken his best columns during the 30 years he was the editor and reprinted them in “Honest Labour” for you to enjoy and think about. Each column occupies a single spread in the book – just open the book to any page and you will find a complete column. And each is illustrated with drawings from that particular year of The Woodworker – many of the drawings from Hayward’s own hand.

“Honest Labour” is the fifth and final book in The Woodworker series, which was a multi-year, multinational project to preserve the hand tool knowledge that almost disappeared in the 20th century. “Honest Labour” is the same trim size as the other Woodworker books in the series, printed on the same paper and features the same tough binding. The only difference is the cotton cover cloth. We chose a deep scarlet instead of the green to differentiate this volume from the others.

The book is currently at the printer and should ship in early May 2020. We hope our retailers will carry this book, though we have no control (obviously) over their stock choices.

In the coming weeks we’ll publish an excerpt for those of you who are on the fence or unsure this book is worth your time and effort.

— Christopher Schwarz

P.S. I know we have been releasing a slew of stuff this week – pinch rods, linocut prints from “Good Work” and now this book. It was completely unplanned and is what happens when you run a publishing company with the “it’s done when it’s done philosophy.” Sometimes that means you have nothing. Sometimes it means you have too much.

Then two boxes arrived at the front door. Inside were the first copies of “

Then two boxes arrived at the front door. Inside were the first copies of “