underside of this sawbench. This “resultant” angle allows you to drill the holes for your

legs with one line and one setting of your bevel gauge.

The following is excerpted from “The Anarchist’s Design Book,” by Christopher Schwarz. The new, expanded edition of “The Anarchist’s Design Book” is an exploration of furniture forms that have persisted outside of the high styles that dominate every museum exhibit, scholarly text and woodworking magazine of the last 200 years.

There are historic furniture forms out there that have been around for almost 1,000 years that don’t get written about much. They are simple to make. They have clean lines. And they can be shockingly modern.

This book explores 18 of these forms – a bed, dining tables, chairs, chests, desks, shelving, stools – and offers a deep exploration into the two construction techniques used to make these pieces that have been forgotten, neglected or rejected.

“The Anarchist’s Design Book” is available for order in print, or you can download a free pdf (and you don’t need to register, sign up for dumb marketing or even tell us who you are). Just click through this link and you’ll find the download in the second sentence of the first paragraph – the one in italics.

“Rake” and “splay” are terms chairmakers use to describe the compound angles of chair legs. If you look at the front of a chair (the elevation), the angle that the legs project out is called the splay. If you look at a chair from the side (the profile), the angle of the legs is the rake. (These angles are usually pretty low numbers – 5° to 15° – in typical work.)

I’ve built chairs for more than a decade, and I don’t mess around with describing or measuring rake and splay much, except to explain it to other builders.

Instead, I use the “resultant angle” – one angle that describes both the rake and splay – and “sightline” – a line where the leg appears to the eye to be dead vertical. You can calculate this angle with trigonometry, but there is a simpler way to think about compound leg angles for those of us who consider math a cruel mistress.

First you need to find the resultant angle and its sightline. You find this by locating the point at which a single leg appears to be perfectly vertical.

If I’ve lost you, try this: Sit on the floor with a chair in your house. (Make sure you are alone or are listening to Yes’s 1973 “Tales from Topographic Oceans.”) Rotate the chair until the leg closest to you looks to be perfectly 90°. Imagine that one of your eyes has a laser in it and can shoot a line through the leg and onto the seat. That laser line is what chairmakers call a “sightline” – an imaginary line through the leg and onto the seat. Put a single bevel gauge on that imaginary line and you can position a leg in space with a single setting on a bevel gauge. That setting is the “resultant angle.”

Most plans for Windsor chairs include instructions for laying out the sightlines and the resultant angles for setting your bevel gauge. But what if you want to design your own chair? Or you want to build a table, desk or footstool using the same joinery?

So put away the scientific calculator and fetch some scrap pine, a wire clothes hanger and needlenose pliers. We’re going to design and build a simple sawbench with five pieces of wood and compound angles. This model will give us all the information we need to build the sawbench.

Build A Model

When I design a piece of staked furniture, I make a simple half-scale model using scrap wood and bendable wire. This method helps me visualize how the parts will look when I walk around the finished object. The model also gives me all my resultant angles and sightlines without a single math equation.

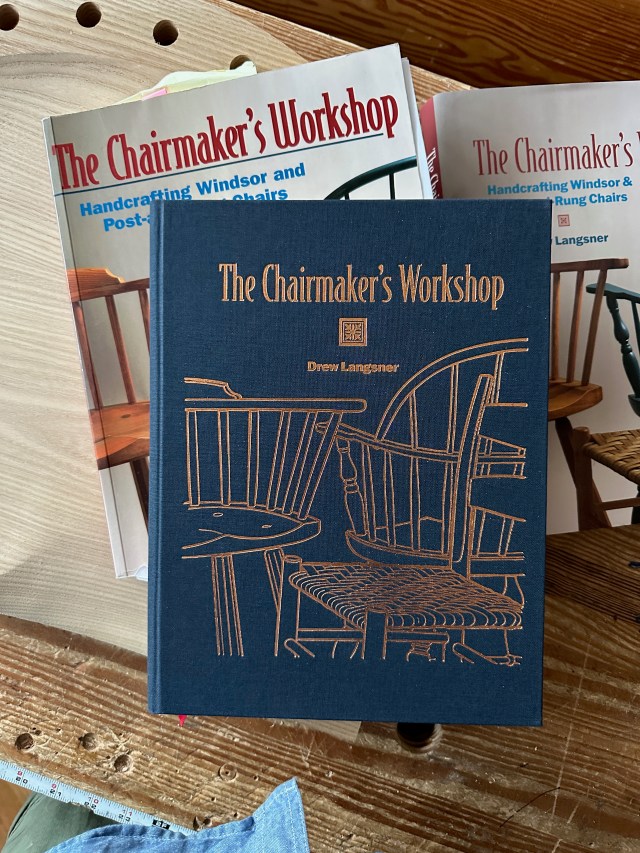

I first learned this technique from Drew Langsner’s “The Chairmaker’s Workshop.” I then adapted his method a bit to remove the math. Let’s use it to design a sawbench.

Take a piece of 3/4″ pine and cut it to half the size of the finished sawbench. The finished top will be 2-1/2″ x 7-1/4″ x 17″, so make the top of your model 3/4″ x 3-5/8″ x 8-1/2″. Next decide where you want the legs to be and lay out their locations on the model. Each of my legs is located 1-1/4″ from the end of the model and 7/8″ from the edge. A lot of this is “by eye” so don’t worry too much.

Now snip four pieces of wire from a clothes hanger to 10″ long. This wire will represent the legs of the sawbench. Drill a snug through-hole for each “leg” on your model. Put a little epoxy into the hole and tap the wire in.

strong enough that you can tap it into its

hole on the underside of the model.

Now comes the fun. Set your bevel gauge to 7° using a plastic protractor. Look at the model directly from the end of the board. Let’s call this the front of the sawbench. Use needlenose pliers to bend the wire legs so they all splay out 7° from the top. Try not to manipulate the rake.

When they all match your bevel gauge, change the setting of the bevel gauge to 14°. This will be the rake. Look at the sawbench directly from its side and use your pliers to bend the legs to 14°. You might have to tweak things a bit so all the legs look the same.

of the legs to bend them to 14° to match

your bevel gauge.

Turn the model on its feet and look at the result. You will be surprised by how easy it is to spot angles that look wrong. Adjust the wires until they all look the same and the sawbench looks stable.

Find the Sightline & Resultant Angle

Turn the model back over. Place a square on the bench with the blade pointing to the ceiling. Rotate the model until one of the legs appears to be 90° in relation to the square. Place the handle of your bevel gauge against the long edge of the model and push the blade of the bevel gauge until it appears to line up with both the leg and the blade of your try square. (Hold your head still.)

your square. Adjust the bevel gauge until its blade aligns with the leg and square. In

the photo I am pushing the blade toward the vertical line made by the leg.

Lock the bevel gauge. This is your sightline. Place the bevel gauge on the underside of the model. Butt it against one of the legs and draw a line. You have now marked the sightline. (By the way, it’s about 64°.)

Now find the resultant angle. Unlock the bevel gauge and place the tool’s handle on the sightline. Lean the blade until it matches the angle of the leg. Lock the gauge. That is your resultant angle – about 15°.

of the model. You are almost done. Unlock the bevel gauge.

If your head hurts, don’t worry. It’s not a stroke – it’s geometry. Once you perform this operation a single time, it will be tattooed to your brain. This chapter will explain how to lay out the resultant angle for your sawbench – you’ll have nothing to calculate. But the act of marking out the sightlines will – I hope – make the concept clear and remove your fear of compound angles in chairs.

the leg. That’s the resultant angle – you just did a good thing.