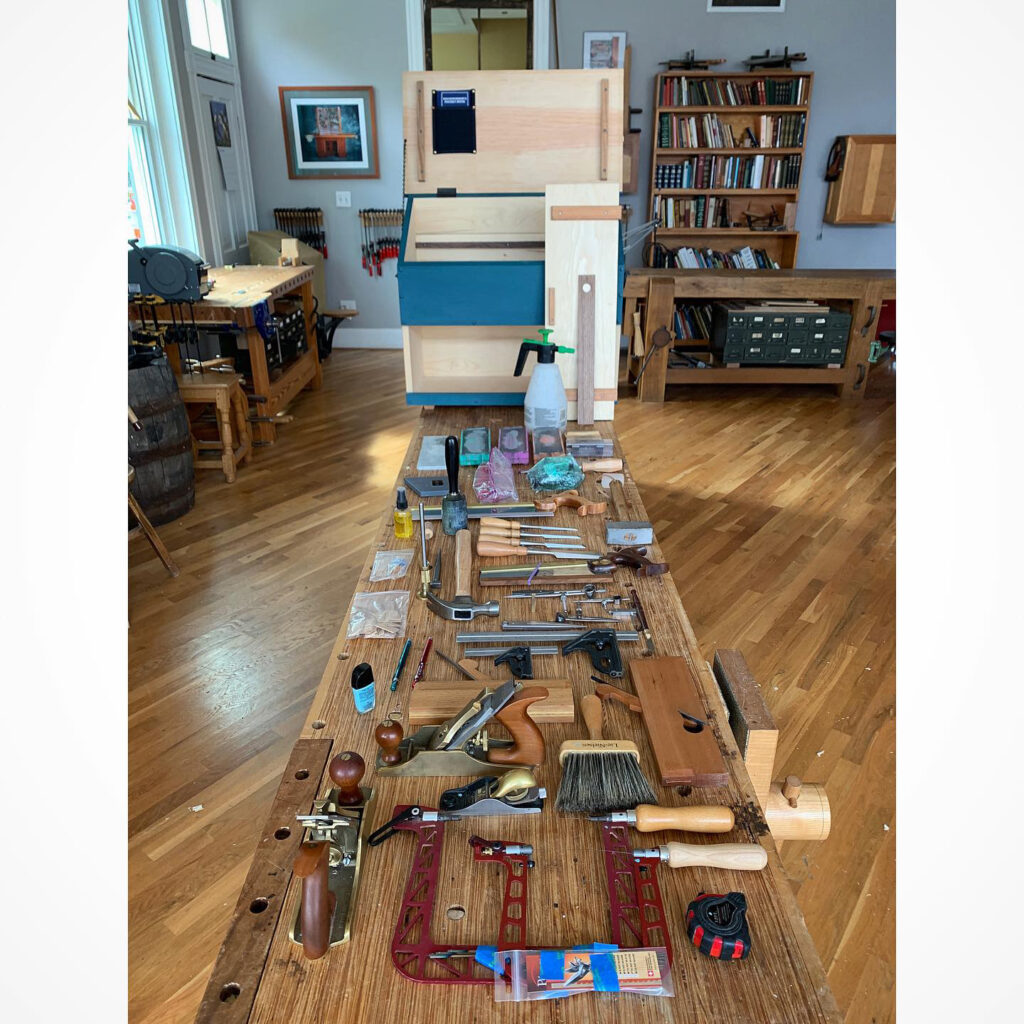

There are still a few spots left in my Dutch Tool Chest class, Oct. 30-Nov. 1 in London, England. In the class, you’ll learn some fundamental hand-tool woodworking skills (planing, sawing and chisel use, as you cut dados, rabbets, dovetails, thumbnail mouldings, chamfers and more – plus how and why to use cut nails) as you build a solid tool chest that will serve you (and your heirs) well for many years. (Note: It also makes an excellent toy chest – kids love the hidden compartment!)

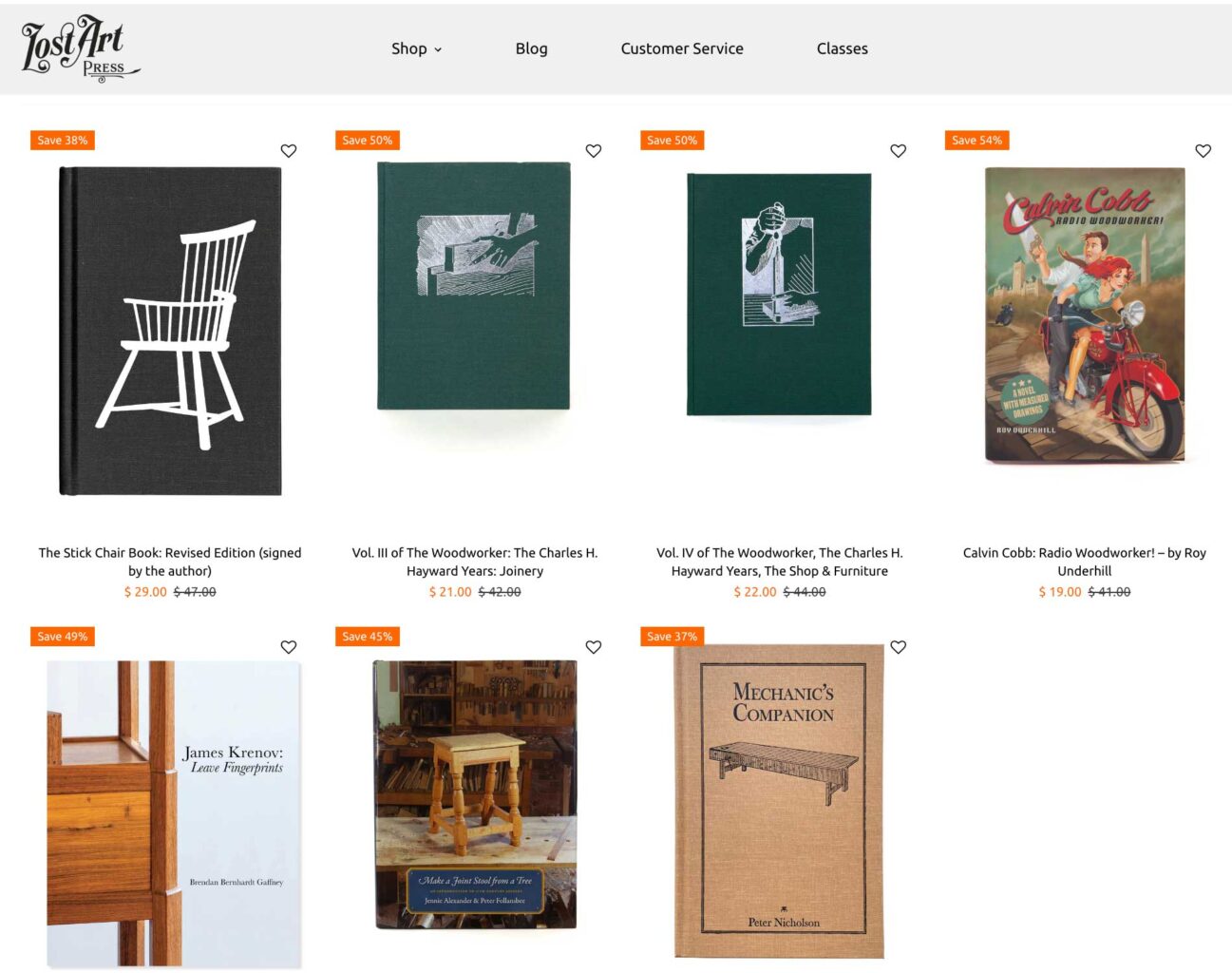

Plus, tickets are go on sale Sat., June 22, for the London IWF Bazaar on Fri., Nov. 1 and Sat. Nov. 2. The bazaar will feature Saturday seminars, with talks on 18th-century furniture, cricket tables, peasant furniture, Shaker furniture, saw sharpening and more, as well as the following vendors: Classic Hand Tools, Lie-Nielsen Toolwords, Lost Art Press (hey – that’s us!), Bad Axe Toolworks, Ian Parker, The Windsor Workshop, Niegel Melfi/Melfi Planes, Michel Auriou, Richard Arnold, Veritas, Sean Hellman, Skelton Saws, St.John Starkie & Bryony Roberts/The Quiet Workshop, Oscar Rush/Hand Forged Edge Tools, Philip Edwards/Philly Planes, Southern Fellowship of Woodworkers, Furniture Maker’s Company, Lowfat Roubo /Derek Jones, G-Sharp Tools/Gervaise Evans, Festool UK, Lamello.

The courses and the bazaar are at the London Design & Engineering UTC, 15 University Way, London E16 2RD.