(You can read part one here.)

Craig Jackson started Machine Time in 2016. It now occupies 25,000 square feet of manufacturing space. The company has 15 employees and plans to hire five more this year. It recently brought on investors to grow even more.

“We mostly do aerospace parts, stupid tolerances,” Craig says. “Some of our tolerances are about the thickness of a Sharpie mark. It’s a whole world that I never truly knew existed. I mean, we’ve got to have temperature control within plus or minus 2°.”

Machine Time’s clients include NASA, SpaceX, Northrop Grumman, Blue Origin and more. U.S. manufacturing is such that Craig doesn’t need to look for clients – they find him.

Even though Craig never knows exactly where the parts he makes end up on rockets, he says he can’t watch a launch. “My feet are sweating, and I can’t be in the same room,” he says. “I just peek at the news the next day.”

Starting Machine Time, and the first five years, weren’t easy.

“From Easy Wood Tools, I had a big house, I had a Mercedes, I had Porsches, I had retirement,” Craig says. “I had to sell it all to fund this place. I didn’t take a paycheck for the first 5 years. My wife made $45,000 a year. We had to move into a house that was the size of a good-size living room, from a five-bedroom, five-bath mansion.”

Craig didn’t draw a paycheck until February 2022.

“Along the way it was so humbling, how many people were rooting for us, you know?” he says. “Chris [Schwarz] was like, ‘Hey, can you make these dividers?’ And I was like, ‘Probably not, but I’ll give it a try.’ I mean, it took us a month to figure out how to make anything at all productively. But now we’ve got an unbelievable team. I mean, a lot of these young guys are just sponges. And the relationship with Chris and Crucible has been pretty awesome.”

Craig says the mix of making, say, rocket parts and hammers, has been great for the young folks in his apprenticeship program, too. Craig says it’s an honor to teach them a solid method to feed their family for the rest of their life.

“Solid,” he says. “They can go to any city in the country and make a living.”

Craig likes to show his apprentices the 38 ways he’s screwed something up and then tell them not to do it that way. Pick any other way but one of those ways, he’ll say. “Let me know how it works.” He loves being a machinist.

“It’s all I’ve ever been, a machinist,” he says. “I just think, I was made to do this. I’ve tried to not do it. It keeps coming back. It’s what I enjoy.”

Craig likes taking a big 600-pound hunk of aluminum and turning it into a part that might weigh 12 pounds, something thin, like a skeleton.

“It’s just an attractive process,” he says.

Craig says there are strong similarities and differences to woodworking. When woodworking with machines, often the cutting tool stays still and you pass the work across. In metalworking, it’s the opposite, he says.

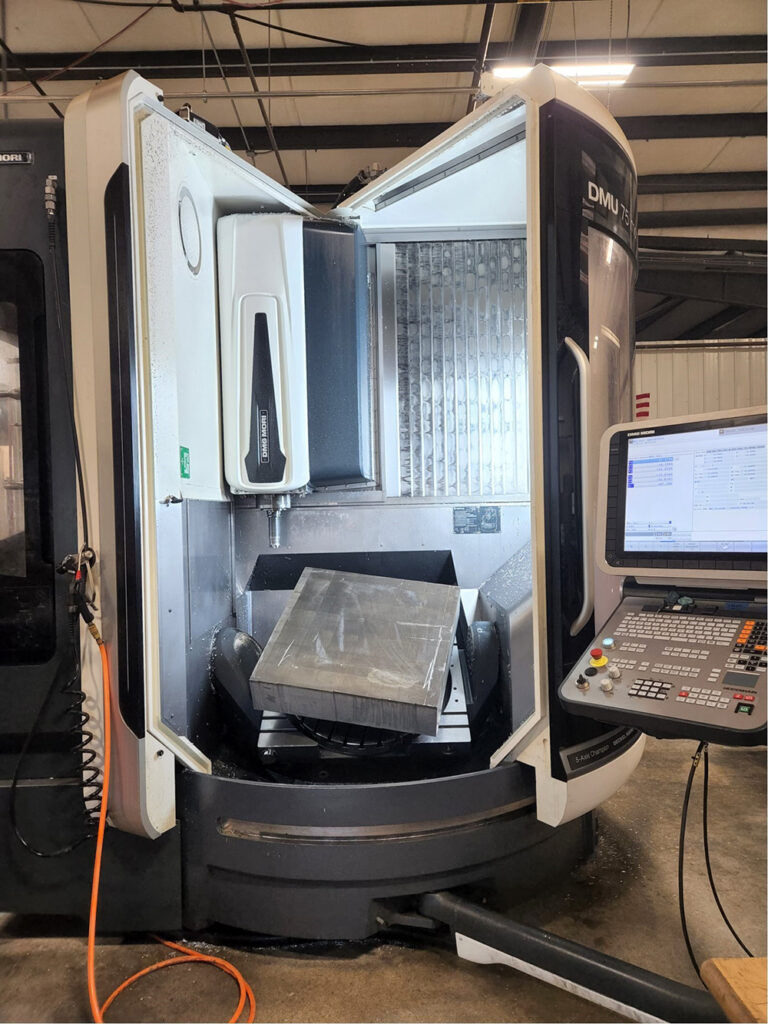

“Really the precision of woodworking is pretty well directly proportional to the hand skills of the craftsman,” Craig says. “In metalworking, at least the parts we do, it’s more about the precision of the CNC machine.”

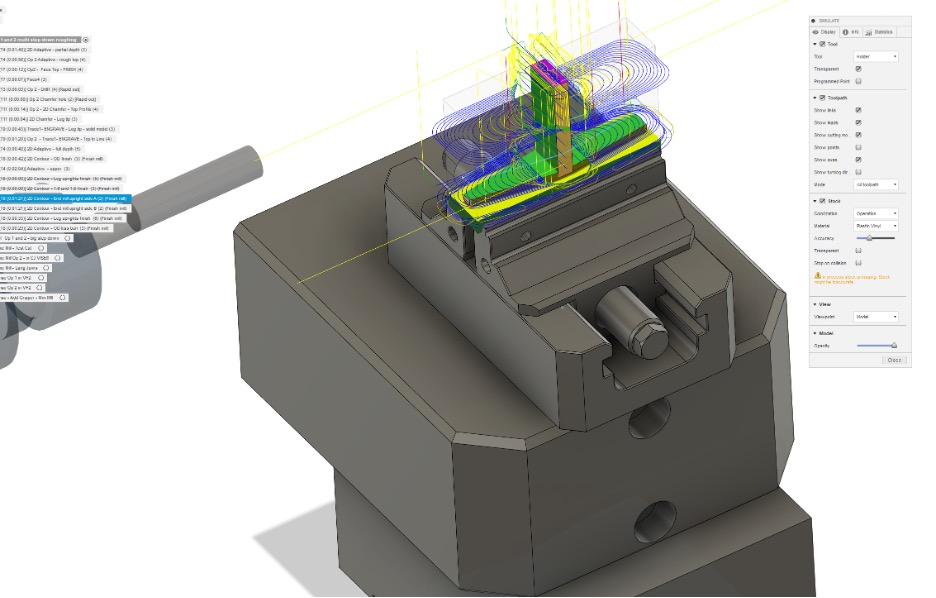

Everything Machine Time makes is programmed virtually via software. Craig and his crew see the entire operation take place on a computer screen first. Once perfected, the program is transferred to a machine.

“Now that sounds pretty straightforward but the devil is in the details,” he says. “There’s a lot of opportunity for mistakes. To program and make a part, it’s probably more than 10,000 decisions. Data points, rpms, speed rates, depth of cut, workholding – it’s the ultimate puzzle, just figuring out how to make this thing. In woodworking, there’s not really that much variety of joints. Everybody has a table saw, a band saw, a router. But in metalworking, I probably have more cutting tools than a whole community of woodworking. And I’m not saying one is harder than the other. I’m just saying there may be more overall variables to deal with…but maybe not.”

Craig uses Crucible’s Dovetail Template as an example.

“To make one of those is a challenge,” he says. “But to make a thousand of them and to hand them off to an apprentice and foresee all the potential issues, that’s a good 180 hours of engineering and prototype work. It’s way up there. Especially on a thin part that can vibrate when you’re milling it. There’s a lot to it.”

And then there’s the Crucible’s Sliding Bevel. A collaboration between mechanical designer Josh Cook and Craig, Craig invented a way to allow users to independently control the rotation of the blade and the sliding of the blade.

“Engineering that, and I had to make a custom workholding, I probably had 400 hours in that,” Craig says. “I like what Chris once said: ‘Well, if you don’t like the price of it, we welcome you to go into small-scale manufacturing.’”

Of course, Craig acknowledges most of us are guilty of this line of thinking from time to time, including himself.

“When I go to the store and buy something made in China or a Mercedes or whatever, I look at it and think, ‘Well they got a machine and they just push a button and it spits it out,’” he says. “We just don’t have enough bandwidth to truly consider the depths of everything in our environment. We just don’t have enough brain to do that. And all we do is cuss when it doesn’t work. How does a car even hold together? There are 10,000 parts.”

Having been a machinist since the early 1980s, Craig has witnessed incredible advancements in the industry. Today, technology is key.

“We have to utilize every bit of CNC technology known to be or we can’t be accurate or we can’t be economical,” he says. An average CNC machine at Machine Time weighs 40,000 pounds, and has a 20,000 rpm spindle with 40 horsepower – and it costs half a million dollars.

“Weekly we’re bringing in new types of technology to the company, whether it’s how to hold a part with custom fixtures or another coolant system,” Craig says.

Always forward-thinking, Craig gets excited about technological advancements. He isn’t sentimental.

“Our vision as a company is to make manufacturing sexy again,” he says.

Craig says when he was a kid, it was considered cool if your dad worked in the plant. But now, it’s the opposite. Technology, he says, has the opportunity to change that.

“I grew up cranking handles on a Bridgeport mill or an engine lathe but machinists now are computer programmers at a basic level, with a high understanding of physics – we know materials, cutting tools and measuring,” he says. “As I get freed up from the day-to-day I’m going to try to hit the road and talk to colleges and high schools and just show them what we do, show them rocket parts and how we go about all this.”

Craig asks, “Have you ever seen a movie, heard a song, read a book that has a machinist in it?” He can think of one: “The Machinist.” It was a 2004 psychological thriller starring Christian Bale. It’s neither romantic nor uplifting. “I just want to see if I can move that needle a bit,” Craig says.

Craig’s vision for the future of Machine Time is to grow: increase benefits, capacity, all of it.

“The complete vision, as bold as it may be, is to create a standard machine shop model and apply it across the country,” he says. “Machine Time Nashville. Machine Time Las Vegas. And so on. That’s the goal. I don’t know that I’m the guy that can complete that but everything we do is in that direction. And whether we do another location or not, those are just good fundamental business practices.”

Craig says if he had $100 million, he wouldn’t retire. He’d have a bigger machine shop.

“We’ve got customers begging us to do more,” he says. “You know, I worked my butt off my whole life but with Easy Wood Tools, I always felt like it came too easy. It was not easy. But I was never sure that I earned it. I can tell you right now, at this point, I feel like I earned it.”

A Life Chronicled in Book Titles

Craig met his wife Donna on a blind date in 1984. She was 14, he was 16. They’ve been together 38 years. Today Noah is 24 years old, Sam is 22. They both work at Machine Time.

“They both went their own ways for a little bit like most all young men do,” Craig says. “You know, your dad’s the biggest hero and the biggest asshole you’ve ever known as you grow up. And then when you go out in the real world, you realize it’s good to have somebody who truly has your back. So they’ve come back to my open arms!”

Craig and Donna live on 5 acres. Craig has a 30’ x 30’ detached garage at home that serves as a workshop – woodworking, as he doesn’t do any metalworking at home. He still loves woodworking and he makes cutting boards, bowls and dining room tables on weekends, giving most of it away to his employees and friends. He stores his wood in a 40’ x 60’ old tobacco barn.

“I love my lumber,” he says. “And bowl blanks. I’ve got two locations for Machine Time and I’ve got wood strewn across these two locations and my basement and my workshop and my barn so I can never find the bowl blank that I’ve got hidden who knows where and I’m still buying more.”

Craig likes to stay busy.

“I can’t even sit down on a Sunday afternoon unless my body gives out so there’s a curse to it,” he says. “Your strength is always a weakness. My weakness is that I can’t sit down and relax. Vacations, I’m not so great at that. I’m not saying one thing is better than the other.”

Craig used to travel a lot with Easy Wood Tools – he’d put up to 50,000 miles a year on his truck and fly. There were pluses and minuses. His boys were pretty young, but Craig says Donna likes to remind him that the family saw the country. They took the kids skiing, to Cancun, to Disney. They did all kinds of stuff. So although he was away from his family for periods of time, he also had the freedom to spend extended periods of time with them, too. These days?

“I don’t want to leave Donna, not even for an evening,” he says. “She’s my best buddy.”

Craig went through a really difficult period when he didn’t get all his money from Pony Tools and had to sell everything to start Machine Time.

“I about lost my mind,” he says.

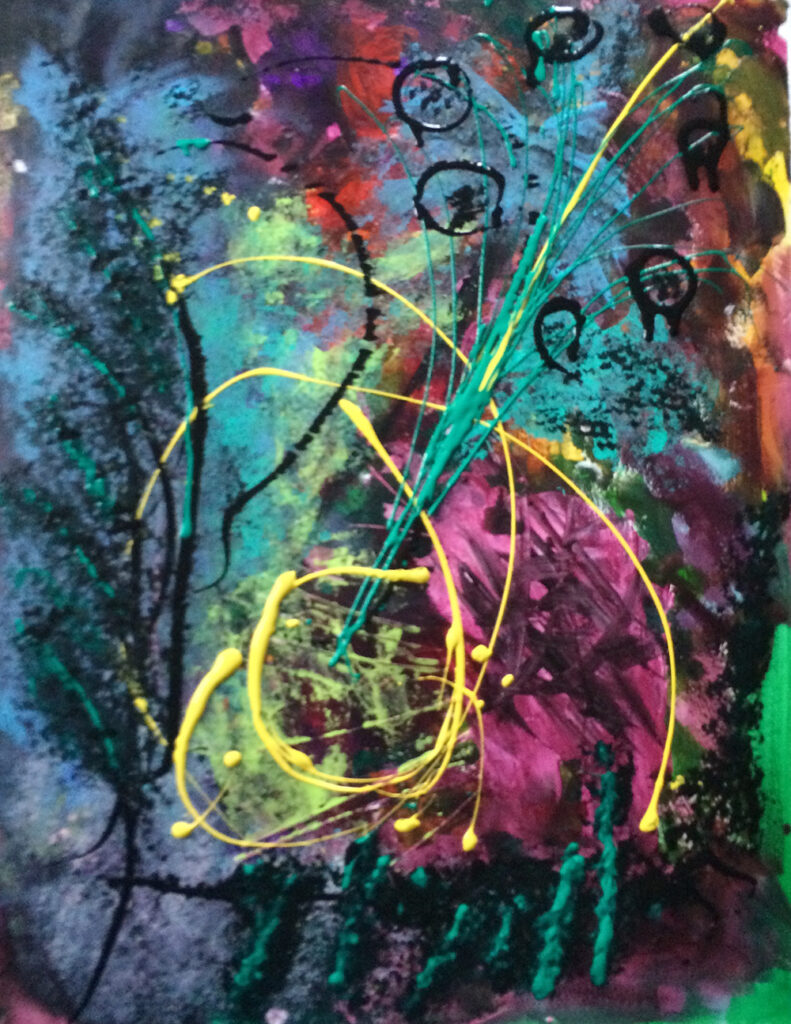

To cope, he started acrylic painting.

“It’s probably the most emotional thing I’ve ever done,” he says. “You know the fear of failure? It’s not like making a machine part or making a table or making a bowl. Because I never know what the results are going to be. I don’t look at anything. I just smear it out. And it’s an amazing release. And maybe that’s because of the point in my life when I started doing it. I’m not an artist on paper at least, but it truly helped me keep my sanity. So I paint when I have to.”

Craig spent the morning of our interview cleaning up 100 gallons of coolant that had spilled out on the floor from a CNC mill. He was mopping it up, throwing wood chips on it. The way he talks about setbacks, big and small, is admirable. They’re all lessons.

“Those lessons, from the bad times, oh my gosh, they’re so much better than the good ones,” he says. “Anybody can do good times and I don’t know if there are any lessons in them, really.”

Around the time Craig sold Easy Wood Tools he also started taking notes, called Book Titles. Today he has hundreds of them, a compilation of big statements condensed. Sometimes he quotes famous philosophers and makes notes. For example:

“The measure of a man is how much truth he can stand (truth always demands change). Nietzsche. AKA – Don’t fear the facts.”

Sometimes he writes his own. For example:

“The universe owes no debts. AKA – Believe that your effort is worth it.”

He calls them learning statements.

“They’re hard-earned and they came at a price,” he says. “And each of them came from a particular moment in time.”

His biggest one?

“Be willing to accept the consequences of doing the right thing.”

The Consequences of Doing the Right Thing

When Craig worked at the tobacco company, the HR manager told him that one day, when she interviewed there, the general manager asked her, “What makes you a good person?” And she told Craig that she didn’t have an answer for that. Craig thought about this for a few days.

“For me,” he says, “it’s, I’m willing to accept the consequences of doing the right thing. And so is Chris. And so is Megan [Fitzpatrick]. I think the word consequences is so often associated with ‘violation’ or ‘you broke the law.’ But the true consequences in life are for doing the right thing. And that’s the best long-term solution. Just look at the long-term. Just think about that, five years from now.”

And five years from now, Craig just wants to keep making ever-more difficult parts.

“It’s all about making jewelry, make it perfect, make it to print, make it amazing to the customer and then we’ll see if we can make money at it,” he says. “I don’t know if I even care about the money. I don’t know. I don’t know that I do.”

Craig likes to tell people this story.

“I feel like when I meet my maker, he’s only got one question: ‘Did you do everything you could with every day I gave you?’ I’ve already got my answer. So when things get too easy, I feel guilty. I’ve got to do more. I’m still walking. Chris is the same way. I’m not the only person. I’m not saying any of this is unique to me, that’s not my point. Everybody’s got me in them. But I’ve got everybody in me too. And we’re all just trying to get through the day and go to bed.”

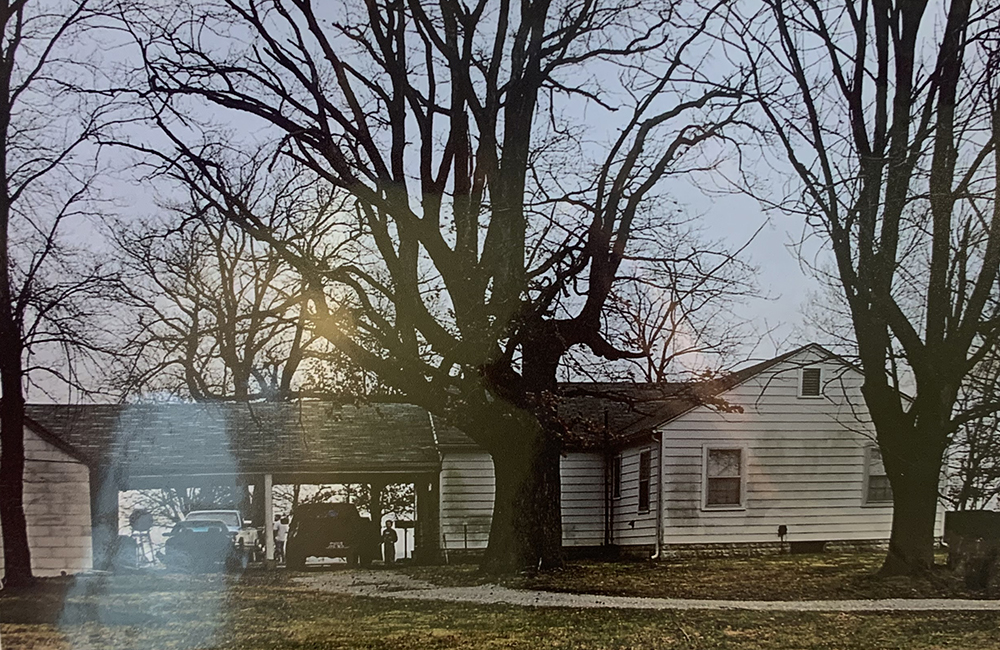

One morning in 2020, as Craig was driving to Machine Time, tired, his funds drying up more and more by the day, he saw a familiar barn, for the first time really, along the way.

“These words came to me instantly and I pulled over and jotted them down just as I heard them,” he says.

Today, he has them printed and framed, below the above illustration of the barn.

Leaning, but not falling

Falling, but not hitting the ground

Hitting the ground, but bouncing

Bouncing, to my feet

Stepping, but not walking

Walking, but not running

Running, into the wind, and leaning

— Kara Gebhart Uhl