Peter Galbert is proof that risk-taking pays off. Author of “Chairmaker’s Notebook,” Peter is a teacher, chairmaker and experimentalist. He was also one of the first Meet the Author profiles for Lost Art Press. And with his boundary-pushing research and a second book on the way (“Chairmaker’s Notebook Vol. 2,” slated for publication in the spring 2025), Pete is still working to create a world with fewer stopping points.

Like a lot of creatives, Pete struggled to make sense of his role in a seemingly complete world.

“The world that was built up around me seemed really weirdly impenetrable, growing up,” he says. “Everything seemed so already completed. When we got to the end of the 20th century, I thought ‘What are we supposed to add to this? Somebody already figured out how to make the covers for taillights, for God’s sake. What is my place in all this, as someone who is interested in making things? How does it all work?’”

This kind of early introspection and natural curiosity led Pete to move from his home in suburban Atlanta to see what else was out there. He wasn’t very enamored with the world of high school, disillusioned by a seemingly unshakeable awkwardness.

“But who isn’t awkward in high school?” he asks. “I’m still waiting to grow out of it. I plan for next year; I’ve got high hopes,” he adds, laughing.

Peter left the South behind and adjusted to the shock of Chicago winters (and seasonal affective disorder). The transition opened up the world for him, going forward. He says it was a very productive time, and formative.

“I’ve always been pretty comfortable making stupid moves,” he says. “Giving in to impulse, in the end, serves me well.”

That impulse sent him speeding past the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and he embarked for a year on the road. He drove across the United States and started working with his hands – renovations, gallery jobs, apprenticeships. He settled at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign where he studied photography.

His interests in photography are tied to sparking curiosity and credibility of truth.

“In any sort of making, you’re always alluding to things,” Pete says. “You’re always referencing something, through history, narratives or associations. Bringing people along through that familiarity, you can push them into a new area, where they weren’t expecting to end up.”

Variations on the classical, or subverting an audience’s assumptions are common themes in Pete’s work. Today, he breaks down traditional forms in chairmaking, but their familiarity is retained.

When moved to New York City at age 26, it was a bloom time of activity. Pete worked with furniture makers and cabinetmakers and built sculptures for artists.

“It was a very informative period,” he says. “I saw doors close, and doors open. I thought, I’m not cut out for the art world. I saw the writing on the wall, the closer I got to it. I’m just not that person.”

While in New York, Pete got interested in woodworking. But at the time, the hand tool green wood revolution hadn’t started yet. He was making his own handplanes, experimenting with new tools and techniques.

“I was into learning hand tool techniques,” he says. “But I was nearly laughed out of every shop I was in, almost while I was doing it. They were like, ‘You’re just never going to see that make money. We need to just cut plywood and get on with it.’ And to some degree they were right. But as time has gone on, it’s been really interesting and fun to see how much interest has bloomed on that side of it from enthusiasts and makers now.”

Then, one day, Pete noticed a “for rent” sign while walking the streets of Manhattan. Inside was a 20’ x 12’ storefront workshop, partly occupied by a guitar maker, Justin Gunn.

“He was capable of building a whole guitar on a benchtop with hand tools and I was so impressed with how organic the process was. He took wood and transformed it into something that could be appreciated for more than just its structural integrity or its surface appearance, the tonal quality was like magic. I was super jealous of what Justin made and how he made it. I wanted something like that.”

Pete paid $400 a month to share the space with Justin (who later moved to Holland with his Dutch girlfriend and became a musician). Given that Pete only had room enough to use hand tools, and his desire to build something both beautiful and functional, he set out to make a chair. This pivotal turn in his life happened, in part, because he felt adventurous and – having just finished a project – he decided to break from routine and walk down a different street that day in Manhattan.

“You know, it’s funny because I see myself as rather insular,” he says. “I’m a bit of a homebody. I do my routines. My dog and I basically operate on the same schedule. Although I tend to be pretty provincial in many ways, I’m not that risk averse when it comes to embracing possibilities. If I see something happening, I jump right on it.” In Gunn’s workshop, Pete became a chairmaker.

Finding Community & Creativity in an Old Mill

“Woodworkers are notoriously a romantic lot,” Pete says. “They pour their heart and soul into it and get pennies out. It’s a very tough, tough business.”

By 2000, the low-rent-in-Manhattan gig was up. Pete was faced with a choice: rent another workshop way out in Brooklyn and continue to struggle with the lack of materials (trees) or move to the country. Two hours north he found a farmhouse with 50 acres that he could rent for the same amount of money he would have spent on workshop space in Brooklyn.

At first, Pete lived the country life only part-time. He and his wife at the time commuted back and forth each weekend. But when his then-wife became fed up with corporate life in New York City, and they recognized the fact that they were never very happy on the return drive each Sunday, they took it as a sign and moved to upstate New York for good.

In 2010 Pete moved to central Massachusetts, lived there a couple years, divorced, and lived there for a couple more years. He then moved to Boston. Despite the city living, Pete had a small yard with a separate garage. He worked in a 20’ x 20’ workshop, located close to North Bennet Street School, where he also taught.

In our previous profile, Pete pined for the countryside. And he got there. Pete now lives in a small cabin on a friend’s sprawling New Hampshire property. In his free time, he enjoys the routine of walks through creeks and glens with his rescue dog, Georgia. Georgia started off very shy, and socializing with students took time. Now an integral part of Pete’s ecosystem, she can help students like they helped her. “Something I think is interesting about classes and teaching adults – adults are very good at their lives,” Peter says.” Whatever they’ve done in their lives, whatever has brought them to be able to afford a class and decide to do this, they’re good at it. So when they come into a place where they don’t know anything, or can’t do things, or have to learn things day in and day out, it’s stressful. Even though it’s exhilarating and they do it because they love it, they do need to pet a puppy every once in a while.”

This is a shining example of Pete’s teaching philosophy. Accommodating and leveling with students is a cornerstone of his approach. “My students and I, I feel like we’re all on the same road,” he says. “We’re just at different places on it. We’re all the same person, we’re all walking into the workshop not knowing, and trying, and hoping for the next skill, next achievement. The process is very human. And I think the art of it is trying to remember that when you’re working with folks, you need to help them exactly where they are. A friend of mine, Kelly Harris, is amazing at this. I’ve watched her teach and it’s jaw-dropping seeing how comfortable she is understanding where the person starts. She just sees it from their eyes so beautifully. That’s something I think is vital. It’s one thing to have the chops, but to be able to break it down and communicate it and transmit it is as much a skill as the skills themselves. When you see it done right, it is profound. It’s really wonderful, and sharing that is a lot of fun.”

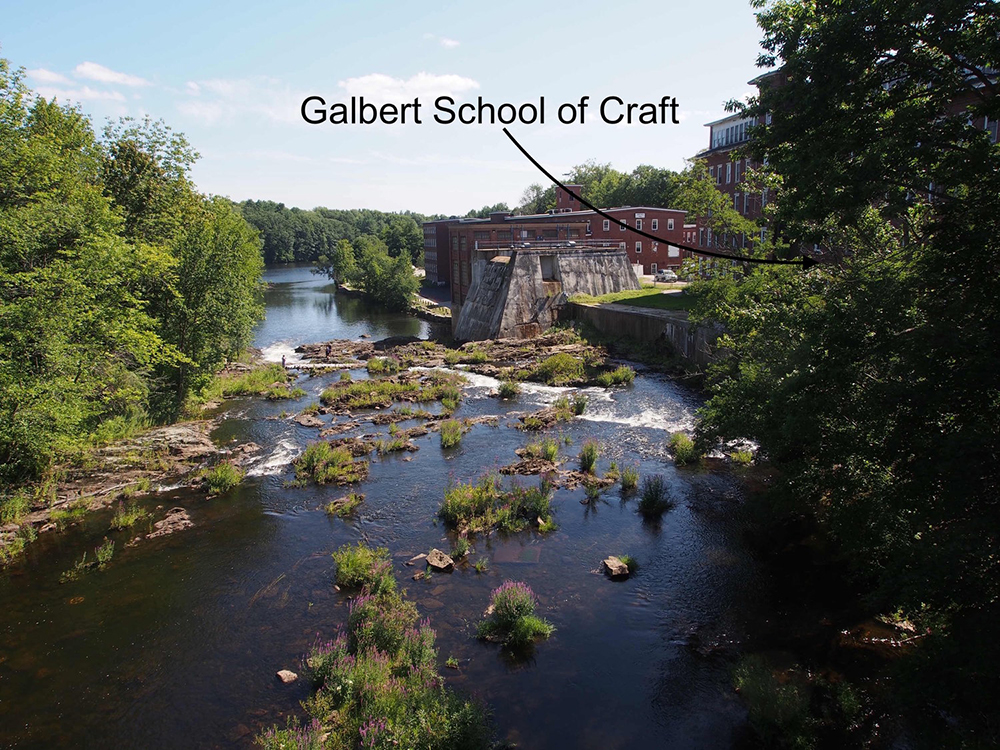

Pete has workshop space in The Mills at Salmon Falls in Rollinsford, New Hampshire. The five-story mill, built in 1848, has been converted to accommodate more than 100 artists, including 30-something woodworkers.

“There was space available, and it was reasonable,” he says. “I was being very practical, but I also saw the potential for a community. Since I’ve come up here, a community has grown. A number of people have come to work with me, or peripherally their partners who are creatives. Now we’ve got a little gravity going now, people are starting to show up to be a part of it.”

Pete’s orbit is undeniable. And the mill seems miles away from any art world exclusivity. Teaching is an important part of his work, but his approach is quite different from the years he spent traveling to share his knowledge. Today, Pete only teaches at the North Bennett Street School or at his shop. Pete is also giving classes to and hosting the next generation of woodworking teachers. A big part of these classes, he says, is career advising. One thing he likes to share with his students is the breakdown between the trade and the craft.

“This notion that you’re going to be a rock star who just makes stuff at the edge of your ability all the time. That’s just not the life it really is,” he says. “You have to think of creative ways to continue to allow yourself to stay on the edge of your interests.”

‘The Love of Learning is What Binds Us‘

Pete has surrounded himself with inspired and motivated makers. And in his design process, you can see a man on the edge of his creative ability.

“You can’t see around corners, so you have to start with one interest, march to the end of it, and see where that takes you and be open to where it might go,” he says. “There are just a lot of different places you can push a chair, which is one of the reasons I still see it as a Wild West. There’s so much untrodden territory. It’s kind of like writing. Everything has been said, but you can still write a really profound book, poem, or anything. Even though it’s just 26 letters and everything has been said. Chairs offer so many frontiers, comfort, aesthetics, structures, materials. So I go at it like, ‘Wow, if I can move this forward, what can that open up in the other categories?”’

“I’m very comfortable ruining things,” Pete says. “That’s been a running theme in my life. I leave a long trail of broken crap behind me.”

Along with Charlie Ryland, who works and teaches along side him at the Mill, Pete has been working to develop technology using kiln-dried wood in place of green wood. His motive behind the technology? Accessibility.

“One of the biggest things that has compelled me recently is the lack of resources so many of my students have faced over the years,” he says. “I knew there were issues with sawn and dried woods to be dealt with, but I thought, ‘Why don’t we beat our heads against this and see if we can get it to budge?”’

He and Charlie worked tirelessly – soaking, shaving and playing with sawn and dried ash until it very closely resembled green wood.

“You can split it, shave it, carve it, bend it,” he says. “It has the strength, all the working properties of green wood.”

This technological feat is part of the focus of Pete’s upcoming book with Lost Art Press.

Pete comes from a background of collaboration and toolmaking. Now, he’s working with The Chairmaker’s Toolbox on tool design and consulting.

“This is where my tool-making interest is right now, which I’m always fascinated by,” he says. “It kind of goes back to that notion of when you’ve made a tool, the world becomes so much more malleable to you. Give me a problem that I don’t know the answer to and I am just giddy.”

Problem solving is less of a trench, and more a long walk to the ice cream store, explains Pete. In terms of experimental work, Pete is at a sweet spot. “Now I’ve done it enough to know that we’re going to get there and it’s just wonderful,” he says. “Early on I used to be insecure and I would get really dejected. But now I know where it’s headed. We’ll figure it out, me and whoever I’m working with.”

Ahead of a class he will be teaching for other woodworking teachers, Pete has been thinking about his design process for chairmaking. He poses these questions as a starting point: “Am I interested in a different use of the materials, the tools, a different geometry for the body, a different aesthetic? Or just a general different process that I haven’t engaged in or want to develop?”

Pete says the flow state he often finds himself in while experimenting connects his constant quest for exploration and joy of teaching.

“When I get into that state where I have an idea or concept I am trying to realize or communicate, that is the delicious part of it,” he says. “To explain something is every bit as lovely to me as to make it.”

Pete describes what he thinks about his future in woodworking, and plans to foster a community of his own. He talks about Lance Patterson at North Bennett Street School (“that old wizard there,” Pete says) and being a useful part of an ecosystem like that. From splitting his time between the busy mill and a workshop full of students, it’s no surprise that Pete’s vision is milling with passionate makers.

“Honestly, as I’ve gotten older, I don’t always have the same energy to walk into a dark, quiet shop, turn on the lights, and make everything happen on my own,” Pete confesses.

So for now, he’s making magic alongside other woodworkers (with the help of a centuries-old renovated mill perhaps contributing).

Pete’s risk-taking has many different forms. The risk of embarrassment, of admitting fallibility, is one of them.

“When you’re in the shop, hoping nobody walks in while you fix one of your mistakes, that’s you attempting a level of control, knowing full well that what you’re doing is communicating. And you do not want to communicate that you screwed up. Or that you’re incompetent or incapable or didn’t know. Sometimes, those are very humanizing moments for the viewer. People don’t want to see you as careless, but they love to see the humanity. My students always love it when I screw up. Then they love watching me fix it.”

By taking risks, in myriad forms and ways, Pete now understands that his view of the world as a child was, in part, wrong: The world is not complete. It’s penetrable, and actually, quite malleable. And there is always room for growth. Case in point: Pete just started a new Instagram page for the art he makes, including sculpture, ink drawings and watercolor studies.

“The love of learning is really what binds us,” he says. “Not even the love of the object, or the love of the actual process. Just having your brain turned on is exhilarating.”

With “Chairmaker’s Toolbox Vol. 2,” readers will be treated to Pete’s brain turned up to max volume, all thanks to his experimentation and exploration, not being afraid of failure, and surrounding himself with a community that, as he says, “kicks my butt, opens new doors, and inspires me. I’m lucky that way. I’m really fortunate to have those connections. I’ve got a good peer group.”

— Harper Claire Haynes & Kara Gebhart Uhl