Editor’s Note: Philippe Lafargue, along with Michele Pietryka-Pagán and Don Williams, are the folks we have to thank for “To Make as Perfectly as Possible: Roubo on Marquetry,” which we first published in 2013, and “With All Precision Possible: Roubo on Furniture,” which we first published in 2017.

Those editions are now sold out. However, the new deluxe edition of “With All Precision Possible” is now available, and we plan to offer a deluxe edition of “To Make as Perfectly as Possible” soon.

Philippe, Michele and Don are also working on more volumes of Roubo, with a focus on interior carpentry, garden carpentry and carriages.

Philippe Lafargue was born in the southwest region of France, in the Basque country, in a town called Biarritz.

“It’s called the little California of France,” Philippe says. “It resembles the California coast because of the cliffs, beachgoers and surfing. The weather is pretty mild all year round, and you have mountains in the background. I was lucky to be born there and raised there. I had access to the natural beauty of the environment, which was very nurturing.”

Philippe lived with his parents, grandparents and older brother in a small, one-floor house with a basement.

“I would find refuge in the basement because we were crowded in the house,” he says. “I remember the winter months when I sheltered there. The furnace was there so it was warm and I could see the rain falling but I was protected.”

In the basement was an old workbench, anchored to the wall. Philippe worked on projects on that bench, imprecise but creative work that he loved. He also spent a lot of time at his uncle’s farm.

At times, Philippe found it difficult to feel motivated in school outside of the more artistic classes. He loved hands-on classes that inspired new ways of looking at things and doing things. He connected with a teacher at school who helped him get started in airplane model making.

Early on, Philippe knew he wanted to be a cabinetmaker.

“I was fascinated with the work of a cabinetmaker,” he says. “I wanted to be a true cabinetmaker, making case furniture. I don’t know where this came from.”

He wonders if he was, in part, influenced by all the furniture, made by a local cabinetmaker, in his parents’ house.

“You could buy what you could afford at the time, so it’s not very attractive,” he says. “But it’s very well done.”

As a teen, he was set to study cabinetmaking at school, theory and practice. But three months before the course was slated to begin, academic offerings shifted regionally. Suddenly, cabinetmaking wasn’t available based on where Philippe lived, and none of the other options offered to him interested him.

“I told the staff of the school that I didn’t see cabinetmaking there so I wasn’t interested,” he said. “I started looking for an apprenticeship.”

While looking, Philippe was offered an opportunity to attend a school two hours away from his hometown.

“Life is about opportunities,” he says, “but it’s also not being afraid to take the train when it’s going full steam.”

Becoming a Cabinetmaker

Before being accepted into the school, Philippe had to complete a series of tasks and projects. Philippe wonderfully shares that experience in an essay in “With All Precision Possible.”

In short, that summer he found a cabinetmaker who agreed to take him under his wing. In addition to helping the cabinetmaker with odd jobs, he worked through his tasks and projects, the cabinetmaker serving as mentor.

For his first task, Philippe dressed up the face and edges of rough lumber, making it perfectly equal in thickness and length, with hand tools only. Next his mentor taught him how to cut dovetails and he built a jewelry box and bread basket out of mahogany and cherry, using a set of provided blueprints for reference. He also learned how to sharpen chisels and hand plane blades.

This, from his essay:

That summer was an eye-opener in many respects and it cemented my desire to work with wood in some capacity. When fall arrived, I enrolled in my new school as a cabinetmaker. The school was training young fellows like me to be ready to enter the workforce quickly and thus the training was more focused on knowledge and use of equipment than on hand skills. After a summer of working with my hands, I balked. Two weeks into the school year I was certain that this was not the path I was seeking. I asked for an audience with the school director and shared him my dilemma. I told him I wanted to work with my hands and chairmaking would work better for me. I asked to be transferred and bid farewell to cabinetmaking. It is amazing what you can do when you are very motivated and stubborn.

I began my education in chairmaking the following week and while machinery was part of the training, there were many parts of a chair that could only be accomplished by hand, and that suited me just fine. So for the next two years, I learned the art of chairmaking, “industrial style,” which also included making beds and end/pier tables. There was a pretty straightforward approach to accomplishing such tasks. Now I was able to read a set of blueprints and from it, trace all the required contours and profiles used to cut out the necessary chair parts from the lumber. Thinking back, I am still amazed that in that class, all of us could produce an armchair in 24 hours, ready for finishing.

At the end of two years I had a diploma in my pocket and some experience under my belt. Now I could return to my mentor’s workshop and turn on and use all the power tools to my heart’s content, something I had earned and did proudly. I had a great summer in the little workshop that year.

During that summer, a friend told him about the esteemed École Boulle in Paris, which has offered higher education in applied arts and artistic crafts, including cabinetmaking, marquetry and restoration work, since 1886. To enroll, Philippe first had to pass a two-day exam, which included creating a full-size set of technical drawings with accurate dimensions of a Louis XV-style chair. He was accepted.

“It was another world,” Philippe says. “You’re learning about a lot of things, all around.”

After two years at École Boulle, he worked out a deal with the director. He would come back a third year, tuition free, and help fabricate everything that came out of the design workshop.

“That was very cool because they were doing some very interesting stuff, combining not only wood but metal and plastic,” he says.

Now he was firmly planted in hands-on learning and he loved it. But the dream situation was short-lived.

Mobilier National

A couple of weeks into his third year at École Boulle, a teacher told him about chairmaking job openings at Mobilier National, that manages the furniture of the French State, such as the furnishing of ministries and embassies, its storage, its restorations, and its design, notably with the Research and Creation Workshop. It was an opportunity Philippe couldn’t pass up. So he and a friend decided to apply. But first, they had to pass an exam.

When they arrived, they were given an armchair and a stack of wood. On day one, they were tasked with drawing the chair to scale. On day two, they were tasked with using their own drawings to each build an armchair in 24 hours. They both were hired.

Philippe worked there for three years.

“It’s like the history of France in all kinds of objects,” he says. “It was incredible. I saw all the campaign traveling furniture of the Napoleon War.”

Here, for example, Philippe worked on chairs stamped by famous chairmakers of the 18th century. The “users,” often high-ranking government officials, didn’t want reproductions. They wanted original pieces, signed and perfectly restored. It was all cyclical, too. For example, a canopy bed might be used by the president of France while elected for seven years and then returned to be left in storage.

Philippe questioned the restoration work at times, ripping off nails, redoing this, fixing that.

“But there’s so much, that you don’t even consider when there will never be enough one day,” he says. “That’s the problem. You value it differently.”

After three years, Philippe realized the job came to him too young. He could envision himself as head of the section in which he worked, but he wanted more out of life.

“If you stay in a job like that young, you are going to lose everything you have to offer,” he says. “There is no room to express yourself. There’s no room to grow. It’s very limited.”

Philippe went back to South France. He felt boxed in. In France, work is quite compartmentalized and segmented, he says, to the point of being rigid. He knew if he stayed that trying anything new would be complicated.

“So in 1987, I took my bag and went to the U.S.,” he says.

An Internship at the Smithsonian

“In the U.S., I realized quickly that first I had to learn English,” he says. “And I had to think out of the box because I could not just be a chairmaker. If you’re going to be a chairmaker in the U.S., you’re only going to be a chairmaker if you make things that are exceptional. You’re going to find a clientele that wants your stuff and that’s it, but that’s going to be rare.”

Eventually he landed an interview at the Smithsonian Museum’s Conservation Analytical Laboratory (now called the Museum Conservation Institute). The job – the museum’s first wooden objects intern. At the time, Don Williams worked in the lab and Mark Williams was head of the lab.

“I remember the interview in the meeting room,” Philippe says. “I was at the end of the table. I was shaking like a leaf. I knew 200 words of English. I had a little portfolio of photographs. And all these heads of all these sections were bombarding me with questions. It was freaking me out.”

He got the internship.

In his first week, he ended up in New Orleans at a convention for conservators from around the world. His eyes were opened to how other countries view the roles of conservator, restorer and curator. In the U.S., he says, you respect the stain as much as you respect a brand-new piece.

“You respect the history because everything is telling you something,” he says. “We’re just only passing information. We are not here to change information. That’s the big difference. You restore to have something look good. In the U.S., you encapsulate this moment and pass it along. And you remember that the best is always the enemy of the good.”

One day at the Smithsonian he saw someone had left three volumes of Roubo on his desk. Don and Mark asked Philippe if he could translate them.

“I said no. I won’t. It’s impossible,” Philippe says. “I didn’t know enough English at the time and I didn’t think I would have been able to manage that at all.”

While protesting, Philippe opened up one of the volumes and found a plate that shocked him. It was an illustration of a workshop and it looked identical to his workshop in Paris.

“It was and still is exactly the same,” he says. “It’s a row of workbenches. Windows on the left, big windows, floor to ceiling. The same spacing between each bench, the same lineup. On the right you have space to have small sawhorses or your glue pot. And you have an equipment room on the other side. When I saw these pictures, I couldn’t believe it. We haven’t moved from that yet. To me, it was unbelievable.”

In the beginning, Philippe worked closely with Mark, who hired and supervised him. When Don took over as head of the lab, he and Philippe worked well together, connecting over a shared taste in music.

No longer stuck in the role of chairmaker, Philippe decided to spread his wings even more.

Tryon Palace

In 1990, Philippe found a new opportunity as a conservator at Tryon Palace in New Bern, North Carolina. He enjoyed this work for a while, but eventually realized he was missing something.

“I was lacking communication with what I was doing because those objects, they never talk back to you,” he says. “It was a bit too quiet.”

He switched gears to technical services manager, taking care of the well-being of its collections and buildings and its day-to-day operations. He worked up to the role of deputy director, which involved more finance work and human resources, and then helped build the N.C. History Center. In 2014, he was named executive director, a role he had been filling since the 2012 death of the previous director.

During this time, Philippe realized that all of his education, hands-on experiences and exposures to new opportunities had prepared him well for such new and varied work.

“Suddenly, you have all these resources that help you find a solution,” he says. “It’s like when you are building case furniture and you have something that doesn’t work, you find a solution. There is something, a mechanism in place that – click – it goes in. If you’re in a field that’s not quite yours, you use your mechanical skills to resolve stuff. It’s in place. You have learned how to make it work. You pull on your resources. I was glad to have my training because I can visualize things in three dimensions. I can see things very quickly.”

Philippe has found his professional journey gratifying.

“I was able to start from a wooden block but it’s not a block anymore,” he says. “It becomes whatever you want it to become. But you still have this hands-on quick understanding and then up, up, up and you work with people. It just happened to be that way. Primarily, I was able to open my mind. And it’s not always easy. But you make a mistake and you start again.”

Working on Roubo

Over the years, Philippe and Don kept in touch, somewhat sporadically. One weekend, Don called Philippe and told him he had started the translation of Roubo’s books. Don once again asked Philippe for help. This time, Philippe agreed.

Don asked immediately if he’d like to be named as an author.

“I said, Don, I don’t know. Send me stuff. If you like what I do, that’s fine with me. If you don’t like what I do, don’t put me on. So that’s the way it ended up being,” Philippe says. “I had no expectations. I was just doing it to help and for the fun of reading historical documents.”

They found a rhythm. Don and Michele completed their work, then sent everything to Philippe to look at it from the perspective of someone whose native language was French and who had a breadth of knowledge in French historical craftsmanship.

The first book took a while. Philippe worked on it every night after work, for two to three hours. The second one was a lot faster – it took Philippe about six months to complete.

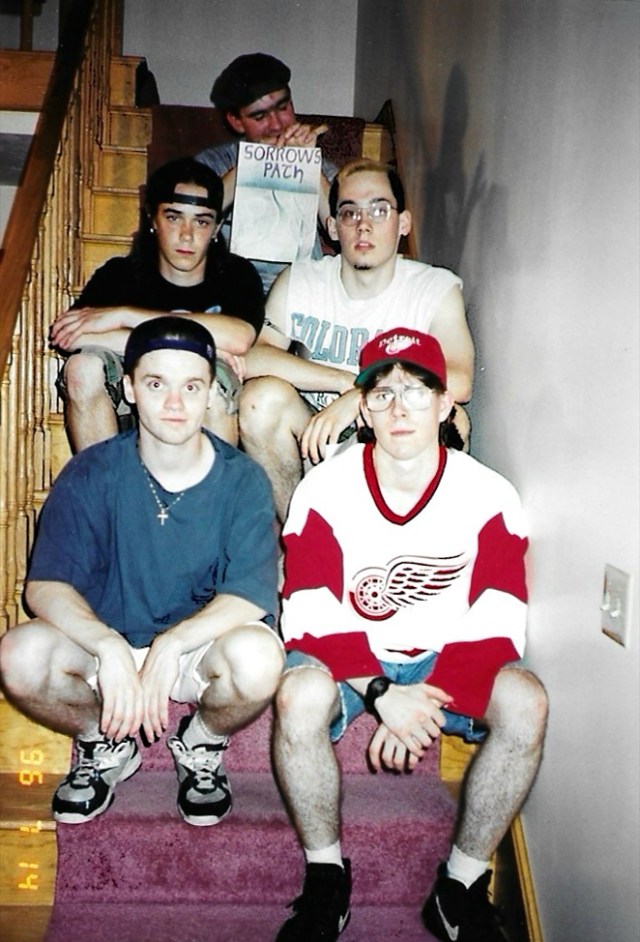

After the first edition of “To Make as Perfectly as Possible” was printed, Philippe joined Don at Woodworking in America 2013 in Cincinnati for a book signing.

“I thought I was on another planet,” Philippe says. “I said, ‘What the heck is going on?’ It’s one of those feelings like you don’t know where you’ve landed. It was funny. Don gave a lecture. I bumped into people like Roy Underhill. I ended up staying with Megan [Fitzpatrick] in her house. She was trying to finish her house. Is she still? I’m sure she is, with all the work she puts in at Lost Art Press. Anyway, Don and I got to see all the beautiful furniture she’s made. That was a lot of fun. It was all very strange but it was one of those moments in life that stays always engraved. You have these beautiful vignettes in life where you cross paths with people.”

Philippe is now back in France, in Saint Nazaire, a small town of about 2,500 people. He’s 20 minutes away from Spain, surrounded by mountains and the Mediterranean Sea.

He’s working with Michele and Don on new Roubo translations.

“That team is very relaxed,” he says. “This is the type of project you don’t get ready for. You can’t work ahead of time. You just wait for it to fall in your lap and then you go.”

‘Life is to Discover Yourself’

Having spent many years living and working in France, and many years living and working in the U.S., Philippe finds the differences quite interesting.

“In the U.S., there’s this quest for success and not being afraid of it,” he says. “There is a lot more freedom available where you pursue things or dream of things.”

It’s an attitude of, Why not? Let’s try, he says.

“What I did in the U.S. professionally is impossible to do in France. You could do it in France, but only if you had the right diplomas. In the U.S., I was not judged by my diploma. I was judged by my character, by my work ethics, by all these things that we should be judged on.”

These days, Philippe had rediscovered the joy of model making (with a nod to his childhood) and he’s tapping into more creative work, creating folk art. He works in a room that is a bit less than 10 square meters, with a tabletop as a workbench. He’s content.

“I’m very curious by nature,” he says.

For example, when making a model sailboat, he also made the sail.

“I pulled out a sewing machine and I sewed the sail because the process was a mystery to me,” he says. “I’m attracted to all those things that are new to me. I have a desire to surprise myself and discover other matter.”

He’s also being mindful about sharing what he’s learned over the years.

“That is also something that is more common in the U.S. than here,” he says. “Here, people retire and are finished. A lot is lost, really. The mentality is really different. In the U.S., when I was working in the museum, we had a lot of volunteers. They don’t want to just stop and do nothing. They come and share their stuff, they participate in life. I don’t know. It’s another way of looking at things. I’m not saying one way is better than the other, but for me, I was glad to be exposed to that way of looking at things because it made me bigger, bigger in looking at things and accepting things and opening up my mind. That’s what I like.”

Living life this way has required him to make some hard choices, he says.

“I’ve learned when you go down river, it’s always easier to go with the flow,” he says. “There’s always something you’re going to be able to catch on the side of the river to make a pause. When you try to go against the current, that’s where you’re drowning and you’re missing all the opportunities.

“You can fight all the time but life is going to take you where it’s going to take you. It’s up for you to go for it, to be quick to accept and change. And you are always part of it. That’s the beauty of it. No matter what happened, you are part of it – 50 percent is your choice. The rest is to accept that you have decided to do this or not. That’s the difficult part. But life is short. Life is to be lived. Life is to discover yourself.”