The first section of my forthcoming book, “Backwoods Chairs,” documents my search for the dwindling ranks of Appalachian woven-bottom chairmakers who count(ed) chairmaking as a significant income. The income piece is essentially my only criteria for the makers: that chairmaking provides at least a part of their livelihood. I had no real idea what to expect when I started my search for ladderback chairmakers. Try as I might to dislodge the romantic vision of a mountain maker working wood on a secluded front porch of a cabin, that stereotype lingered in my brain as I started the search. At times, I found a maker shaving wood parts on the porch. Other times, the idyllic vision was incomplete – as when I visited a maker shaving parts next to a generator, which powered the lunchbox planer used to thickness his chair slats.

Appalachian post-and-rung chairmaking is far more complex than I initially imagined. For starters, the makers do not fit into simple categories. Some make all their income through chairmaking, and others a portion of it. Some do it seasonally, either working around their farm’s growing season or working in the shop during the summer months. One person did not consider himself a “chairmaker” at all, though chairmaking has been a constant in his life for five decades. The whole thing is squishy.

I also recommend readers put aside any tidy categories when considering the makers. The lines between “amateur” and “professional” blur to the point that they are no longer relevant. I found “part-time” and “full-time” categories to be pointless as well. At the end of the day, there are either chairs or no chairs.*

I sought out makers of the basic post-and-rung form, though each maker creates distinctly different work. I think of it this way: Chester Cornett could only make a Cornett chair, and Brian Boggs could only make a Boggs chair (I know, that statement is so simple that it’s stupid). The chair is a reflection of the maker; the maker DNA is right there for all to see. The Cornett chair reveals the use of the knife, and Chester measured everything by his hands and thumbs. His approach helps create that magic in his work, and it’s a constant across his career, from his beautiful common chairs as a younger man to his bombastic late-career rockers.

Boggs’ chairs are refined and highly engineered. There is intention behind each detail, both in the design and the technique. Boggs’ ladderback chair was reimagined into a modern piece in his Berea Chair until it could not be improved upon. Brian took a form typically considered rustic and backwoods and reimagined it for a contemporary setting. He did that by making a chair with equal consideration toward comfort, technique and design. Cornett and Boggs – two chairmakers beginning at the same post-and-rung starting point, yet yielding wonderfully different results.

Whenever possible, I traveled to meet, interview and photograph the makers. I wanted the opportunity to explain by book in person and figured this was my best approach to record and reflect on the makers in the fullest light. The initial interview and meeting proved helpful, especially for photography, but the follow-up proved most fruitful. The makers could size me up and determine if they wanted to provide more to this project. One maker showed me the door after 20 minutes. That bruised my ego a little (was it something I said?) but most followed up by sending pictures and sharing additional stories and techniques. Like James Cooper, most wanted me to get this right. That meant educating me on all things chairmaking.

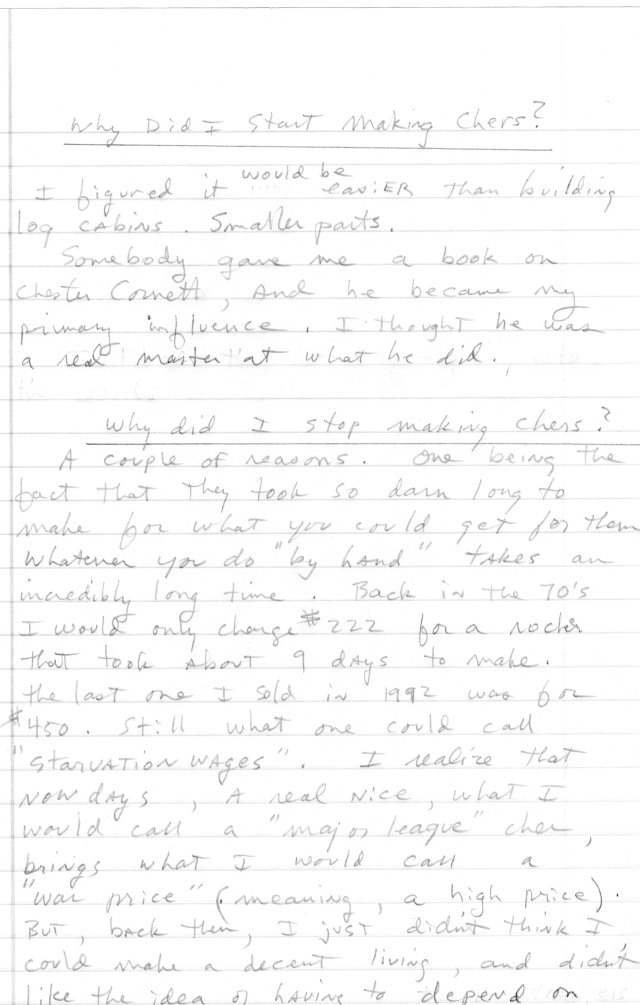

I met Cooper of Jackson County, Ky., earlier this year. We sat on his porch during an early spring downpour and discussed his approach to chairmaking. James crafted handmade chairs as his primary income source for three years in the late 1970s and early 1980s then decided to make a career change. He followed up our initial conversation by sending 10 pages of written notes and a collection of his early photography. With it, he opened my eyes to his reality of making chairs in Eastern Kentucky.

The notes are shared here with his permission.

– Andy Glenn

* A note about categories. I request that the reader does not overlay “morality” onto the chairmaker’s decisions (as in, one decision is morally superior to another). There is a tendency within woodworking circles to philosophically judge the work of others, where handwork can be judged of more value than machine approaches (and this, being a Lost Art Press publication, will likely reach those who appreciate handwork). I propose that an outsider has no say in the decisions of the maker. Decisions are purely personal choices made by the chairmaker.

One example: the chairmakers I met in the process of the book made the following decisions regarding their chair rungs; 1) split and shaved 2) turned from lumber 3) store-bought dowels 4) made on a dowel machine 5) handheld power planer to shape and taper them after using a brace to cut the tenon on the end. One choice is not philosophically superior than another – at least as far as an outsider can judge.

My goal is finding out why the maker decided upon an approach or technique. Is it because they work within an established tradition? Is it for speed and efficiency? Is their design target “old-timeyness” (which deserve the shaved rungs)? Regardless of the answer to those questions, I recommend the “handwork is more pure than machines” belief be suppressed when considering the work of others. Only the chairmaker gets to make that “moral” decision about their work.

After four years of honest labor, I am happy to announce you can place a pre-publication order for our newest book: “

After four years of honest labor, I am happy to announce you can place a pre-publication order for our newest book: “