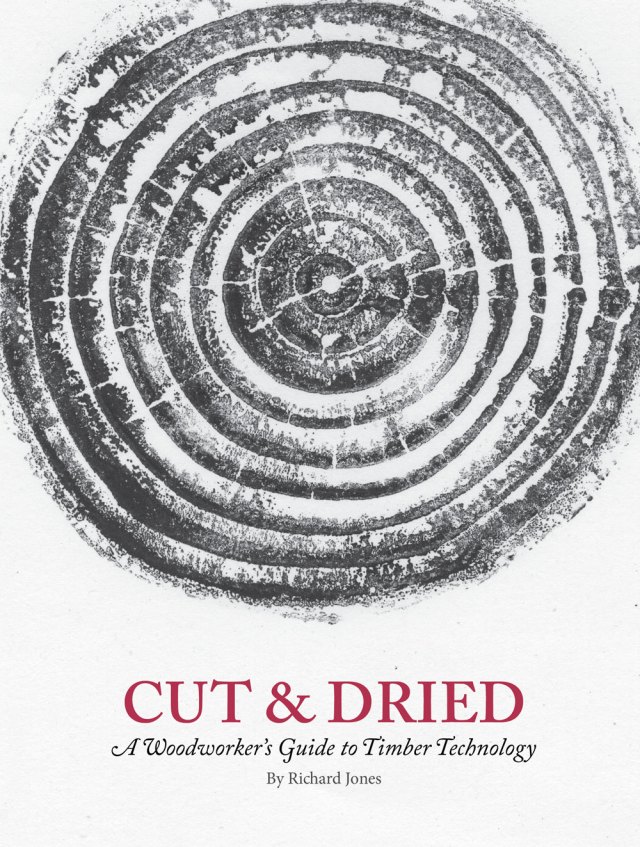

Richard Jones’s opus on wood technology – “Cut & Dried: A Woodworker’s Guide to Timber Technology” – is almost ready to go to the printer. There are just a few last-minute freak-outs to tend to today. And wrapping up the cover, which turned into a craft project this week.

“Cut & Dried” will be one of the largest books we’ve published (at about 400 pages) and covers every aspect of our beloved material, from how it grows, all the way to how it behaves when it’s in a finished piece of furniture. In between, Jones covers every aspect of the material, from fungi and pests to sawmills and kilns.

And, most importantly, the book is told from the perspective of a woodworker. Jones is a lifelong professional woodworker and instructor. While there are many other fine books on wood technology out there, Jones thought they were aimed more at a scientific audience than at furniture makers. And we agreed.

So Jones spent many years researching, writing, photographing and drawing this book to develop what we think is the most complete and understandable guide to wood.

We’ll be talking more about Jones’s exhaustive treatment of the topic in the coming days. But first, a look at how we developed the cover. It also involved woodworking.

“Cut & Dried” delves deep into the structure of trees and how that affects your work at the bench. And so I wanted a cover that displayed the structure without being too technical about it – this book is not written for wood scientists.

During my experiments with shou sugi ban, I became fascinated with how a torch can burn away the earlywood in some softwoods, leaving the hard latewood and exposing the pores that transmit fluid in the tree. I wondered if this could result in a woodblock-like print for the cover. After searching around, I became inspired by the work of Shona Branigan who does this sort of thing but takes it to a sublime artistic level.

This week, Megan Fitzpatrick, Brendan Gaffney and I spent a day messing around with different trees to make a block for the cover. In the end, Megan snitched an offcut of a neighbor’s Christmas tree – a Scot’s pine – that we cut, burned, brushed and inked. It took us about 25 tries to get the look we wanted.

If all goes to plan we’ll be offering this book for pre-publication ordering next week. When it’s released, we’ll have details on pricing and the ship date.

— Christopher Schwarz