Earlier this year, I announced that I wouldn’t be teaching any woodworking classes in 2012 in order to give my family a break from my sometimes-hectic travel schedule.

After stepping down as editor of Popular Woodworking Magazine in June, my wife and I reconsidered that decision, and I will be teaching an abbreviated class schedule in 2012. Many readers have requested my teaching schedule so they can request vacation days from their employer. And though I am still ironing out the details with a couple schools, I decided to go ahead and post my schedule as it stands now.

Some important caveats:

• Some of these topics and dates might change slightly, though my hope is that nothing will change.

• I also hope to teach a class on building “The Anarchist’s Tool Chest” at Roy Underhill’s school sometime in 2012, but we are still trying to find the best dates.

• Registration has not begun at many of these schools for 2012 so you might have to be patient.

• What I am posting below is all I know at this point. So with those big caveats, here is the line-up.

Feb. 25-26

Woodcraft of Atlanta

“The Best Layout Tools Money Cannot Buy”

We build a Roubo try square, inlaid winding sticks and a traditional straightedge, three of the most important layout tools for the hand- or machine-tool woodworker. This will be a one-day class.

Second one-day class: Perhaps something on sharpening, dovetails or building a sawbench. We’re still working on it.

April 10-14 (yes, Tuesday to Saturday)

Marc Adams School of Woodworking

“Build an 18th Century Workbench”

We build the Old-School Roubo workbench using massive timbers and the traditional joints – including the through-tenon and sliding dovetail joint that connects the base to the top. This bench will feature a leg vise as the face vise and an iron quick-release vise for the end vise.

May 5-6

Marc Adams School of Woodworking

“Handplanes and Their Uses with Thomas Lie-Nielsen”

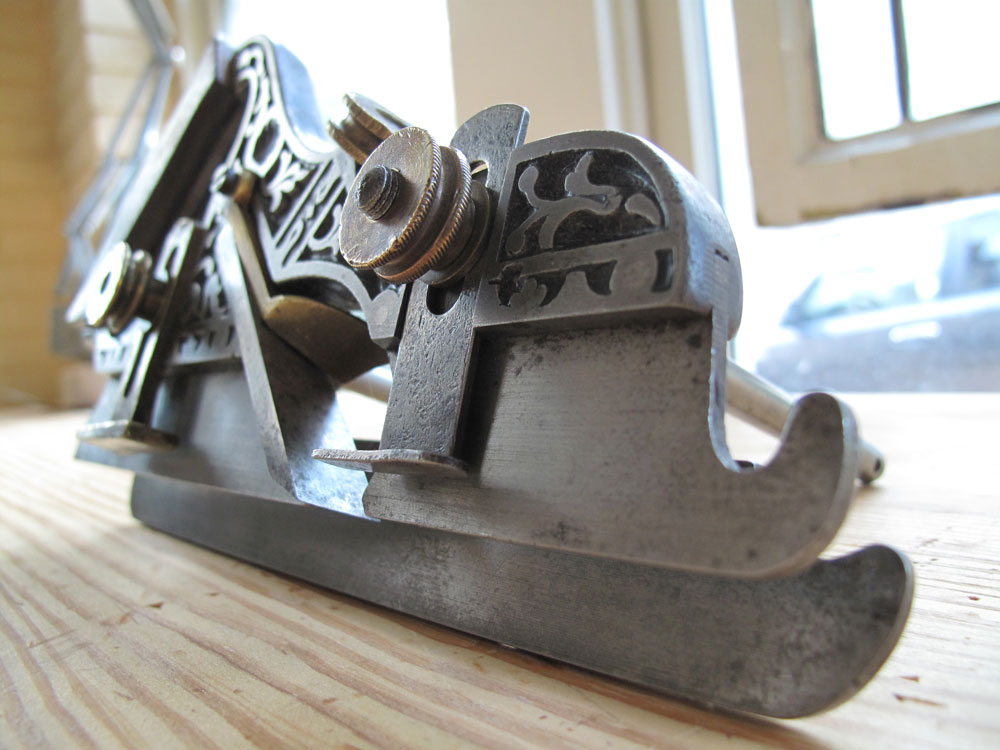

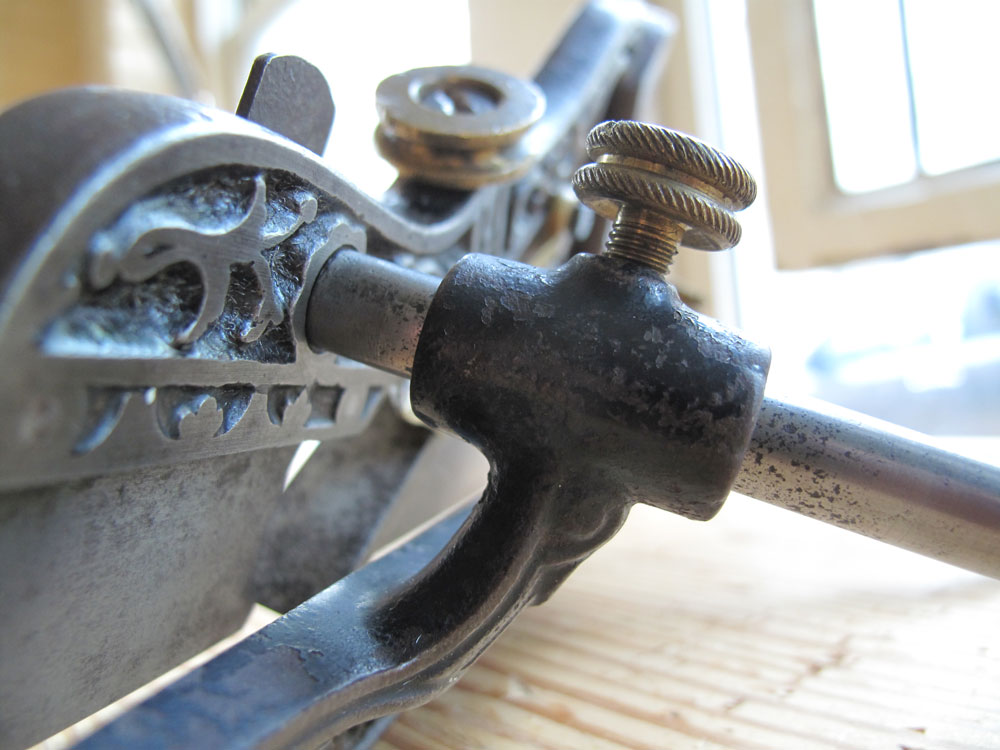

I’ve assisted Thomas Lie-Nielsen for six years now in this popular class in which we cover all the bench and joinery planes. We show you how to set them up and use them to make boards flat and ready for finish, plus how to cut and refine joints.

June 10-17

Dictum Workshops, Metten, Germany

We are still working out exactly which days each class will occur during my eight days there.

“Build Your Own Precision Layout Tools” (one-day class)

Wooden layout tools are lighter in weight, easier to maintain and less expensive than metal layout tools. And they can be just as accurate as metal tools, once you understand how to build them and measure their accuracy.

In this one-day class, we will build the three most essential layout tools for hand-tool woodworking: a one-meter straightedge, winding sticks with inlay and an 18th-century style try square. In the process of building these three tools by hand, you will learn the following skills.

• How to dress boards with handplanes so the work is completely flat and true.

• How to design wooden layout tools so they resist seasonal expansion and contraction and stay true.

• How to test layout tools to ensure they are straight and square.

• How to correct layout tools using simple strokes with a handplane.

• How to add simple inlays of geometric shapes to make your layout tools easier to use and more attractive.

“Master Metal Handplanes and Western Saws” (two-day class)

To the uninitiated, metal handplanes seem too heavy, awkward and complex for fine woodworking. However, once you understand the proper way to sharpen, set them up and use them, you will see why these planes are most popular form of tool in North America and England. Compared to wooden-bodied planes, iron handplanes offer some advantages that you can exploit to do extremely fine work. On the first day of the class, students will learn to set up and use metallic planes so they can produce precision work.

One the second day of the class, we will explore Western saws, including the dovetail, carcase, tenon and handsaw. Students will learn proper sawing technique and how to cut extremely accurate joints using these tools.

“Build an 18th-century Workbench” (five-day class)

Early workbenches were simpler, heavier and better suited for people who built furniture with hand tools. After disappearing from workshops for more than 100 years, these ancient workbenches have become popular again as hand-tool woodworkers have discovered their advantages.

I’ll be leading a class at the Dictum workshops where each student will build his or her own workbench using hand tools (for the most part) and common materials. These benches feature only the best joinery: mortise-and-tenon joints for the base, plus a sliding dovetail and through-tenon joint for the top. The vises on the bench are simple, accurate and heavy: A leg vise on the front of the bench and an iron quick-release vise on the end. You will be able to customize your bench for right- or left-handed work, and you will be able to build your bench so it is the correct height for you and the length of your arms. A properly sized bench is much less tiring to use.

All the benches will be constructed so they can be assembled and disassembled using metal nuts and bolts so they will be easier to transport to your shop.

July 16-20

The Center for Furniture Craftsmanship, Rockport, Maine

“By Hammer and Hand, Build the Dovetailed Schoolbox”

In this fast-paced class we build a Moxon, double-screw vise for dovetailing and a shooting board that works very well as a bench hook. Then we use these two appliances to build the Schoolbox featured in the book “The Joiner and Cabinet Maker,” an 1839 book of fiction written for the young apprentice.

July 30-Aug. 3

Kelly Mehler School of Woodworking

“The Anarchist’s Tool Chest”

We build the full-size tool chest from the book “The Anarchist’s Tool Chest.” This chest features lots of dovetails (you will become an expert by the end of the week) and a very nice raised-panel lid. We will have time to build only the outside of the chest – the shell, mouldings, skirts and lids – but we will discuss how to divide up the interior for efficient work.

Sept. 4-8, 2012 (Tuesday to Saturday)

Marc Adams School of Woodworking

“By Hammer and Hand: The Dovetailed Schoolbox”

In this fast-paced class we build a Moxon, double-screw vise for dovetailing and a shooting board that works very well as a bench hook. Then we use these two appliances to built the Schoolbox featured in the book “The Joiner and Cabinet Maker,” an 1839 book of fiction written for the young apprentice.

— Christopher Schwarz