At Popular Woodworking, we begged readers to send us submissions for the magazine’s last-page essay called “End Grain.” The problem was that almost all the essays we received had the same theme. It was such a problem that the theme became its own compound adjective.

Me: So what’s the essay about?

Fellow editor: It’s another grandpa-was-a-woodworker-so-now-I-am-too piece.

To be fair, my grandfather on my mother’s side truly was an accomplished woodworker. He taught me quite a bit about the craft and inspired me to be a woodworker. So I am in the sizable cohort that I appear to be mocking (though I am not).

Instead, I want to call attention to a fact we sometimes forget. Here it is: We are not clones.

When I write about the woodworking I did as a kid, it’s easy to focus on – duh – the woodworking parts. My grandfather was an enthusiastic woodworker, and I spent many hours in his Connecticut shop making things. My father was also a woodworker and a carpenter and a mason and a talented photographer (and 100 other things). And it’s easy to explain my interest in the craft through those two people.

But that’s just shorthand. And it’s incomplete.

As my father got older, his patience for work in the craft grew veneer thin. When he was younger, he would spend months laying hundreds of bricks by himself (sometimes with the help of my mother) as he started beautifying our first home in Arkansas. After he designed the two houses for our farm, he spent most weekends there (dragging us along whenever possible). These houses took more than a decade to construct. But despite the overwhelming task, he moved forward every week, joist by stud.

Once in his 60s, however, he confessed to me that he’d lost the drive to take on big projects. He was still interested in making things. But he wanted things to be quick. He wanted to learn to turn. And to carve small objects. Up until the end, his hand skills and his mental acuity never wavered. When he did pick up the tools, it was humbling to watch. But it was more difficult for him to ignite that spark. And to keep it going.

I think about that a lot. I have now entered my 50s, and I still want nothing more than to build things day in and day out. For years I worried that I would turn into my father and lose the ember that’s necessary to tackle difficult furniture pieces.

Luckily, I am not a clone. I am also the product of my mother.

My mother, now in her 70s, is as active and entrepreneurial as she was in her 20s or 30s. As a kid, I watched her teach natural childbirth in our traditional (some might say backwards) Arkansas town. She started a restaurant there, and then she worked at restaurants and catering businesses all over the country (Dallas, Santa Fe, Connecticut, Little Rock). Today, she still runs a catering business from her house and cooks every week as a volunteer at our local shelter. And she still embraces new technology (we’re both exploring the world of cooking with sous vide and an Instant Pot these days) and new ways of working.

She has had a more tumultuous life than my father, especially after they broke up. But she doesn’t give up. And she always finds a way to make things work, whether that’s throwing together a great meal with scraps or starting her life over in a new city.

So while it might look like Lost Art Press and my love for woodworking is the direct result of my time in the workshop with my grandfather and father, that’s not quite right. It’s my mother’s influence that gave me the strength to give the finger to my corporate job. And in the 1990s when I failed at my first publishing business, it was my mother’s genes that gave me the strength to say: Hell yes, let’s do this again and start Lost Art Press with my business partner, John.

And it’s also her genes that likely will keep me going.

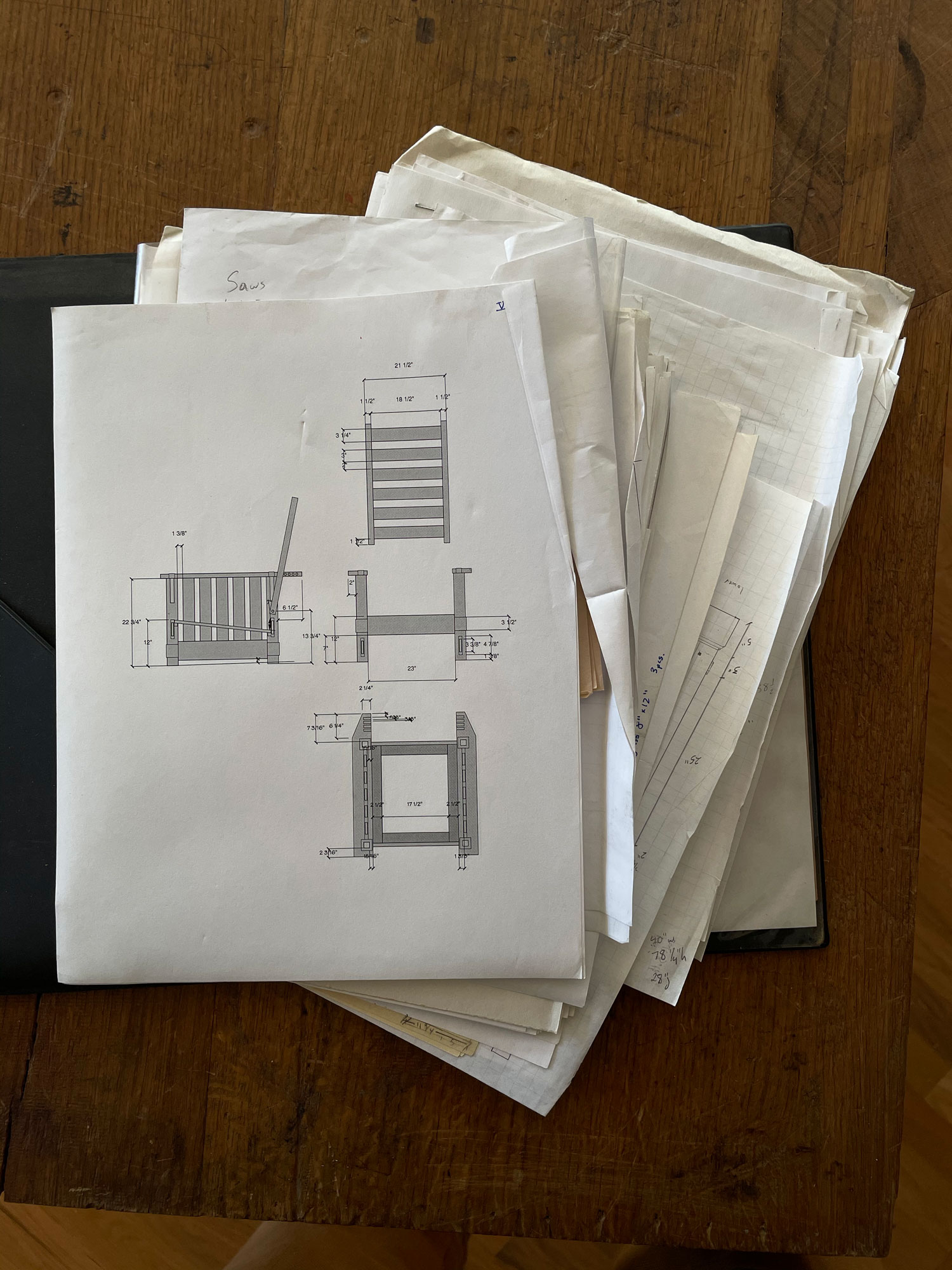

As I get older, my patience for woodworking has only increased. I am still interested in learning new (and sometimes very old) techniques. And John and I have a business – publishing high-quality woodworking books – that is as ridiculous on paper as running a restaurant or a catering business. But we make it work.

So while grandfather might have been a woodworker, it’s important to also remember this: Mama was an entrepreneur.

— Christopher Schwarz

Editor’s note: Nancy Hiller’s “Little Acorns” will return soon. She’s working on a big one now.

Like this:

Like Loading...