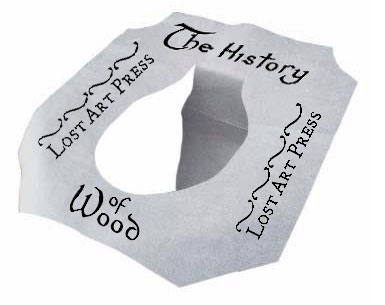

On Tuesday we will begin selling our first-ever sweatshirt: A 100-percent cotton American Apparel zip hooded sweatshirt that features a hand-drawn logo by artist Joshua Minnich. The sweatshirt will be available in small, medium, large, XL and 2XL. The cost will be $45.

Though this seems a small thing – selling a sweatshirt – this product represents almost seven weeks of work for John and me. I had the easy part – working with the artist on the logo. Since August, John has been trying to reconfigure our supply chain for apparel so it’s like our supply chain for our books.

John got us very close to the source and cut out several layers of people who do nothing but pass on expenses. As a result, this sweatshirt will be $45 – a very good price for a quality American-made sweatshirt – instead of $65.

It’s the same strategy we use to ensure our books are competitive.

With any luck, we will be able to lower prices on our hats and T-shirts in the near future, thanks to John’s diligent work.

I’m wearing one of the prototype sweatshirts right now. The logo is fantastic; I like the way the zipper passes right through the compass. And the sweatshirt is as soft as the thigh of emu.

— Christopher Schwarz

P.S. I know these questions will come up: I’m afraid these are the only sizes available to us from the factory. And we are still not able to sell apparel internationally; we hope that day will come.

Like this:

Like Loading...