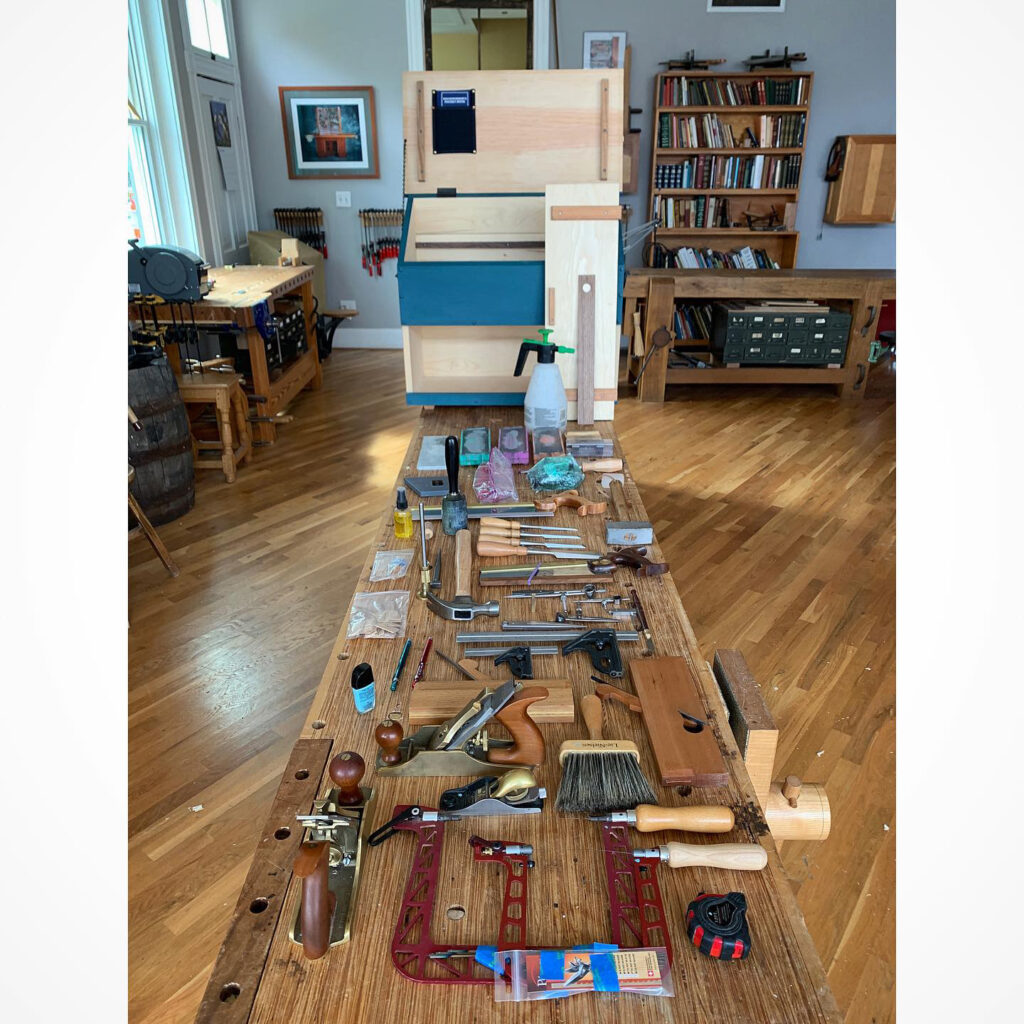

Applications are now open for this year’s full-scholarship class here at Lost Art Press. Six spots are available for six aspiring chairmakers to build a comb-back stick chair in beautiful Covington, Kentucky. The class will be held Sept. 16-20, 2024.

If you aren’t familiar, The Chairmaker’s Toolbox is an organization founded by fellow under-represented chair nerds for under-represented chair nerds. The Chairmaker’s Toolbox aim is to provide access and equity in the field of chairmaking.

Are you an aspiring chairmaker who has been historically excluded from the trade? This is your class. We encourage you to apply for the chance to work alongside like-minded individuals who share a love for all things chair.

Applications are due by July 12th. Apply via The Chairmaker’s Toolbox website.

– Kale