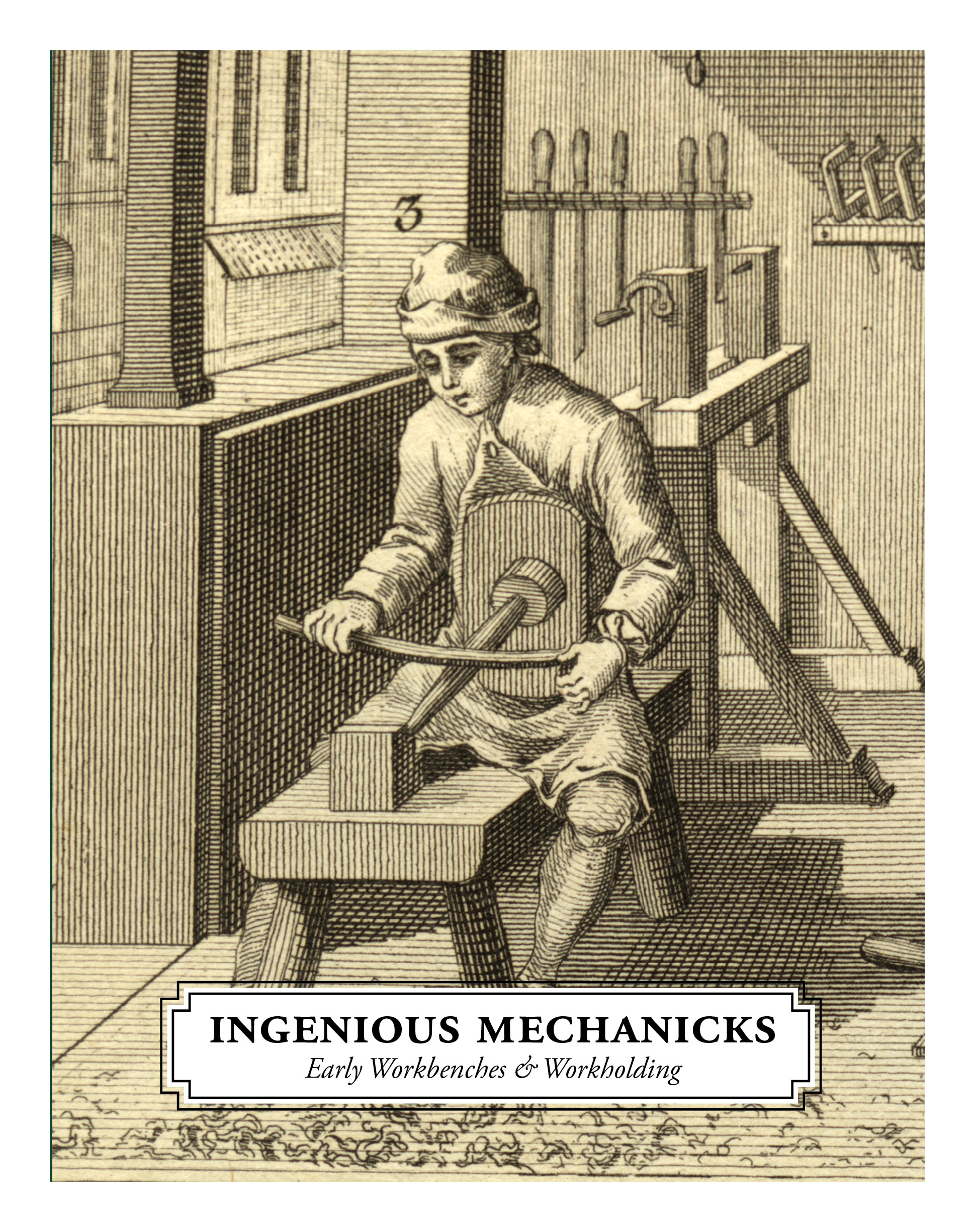

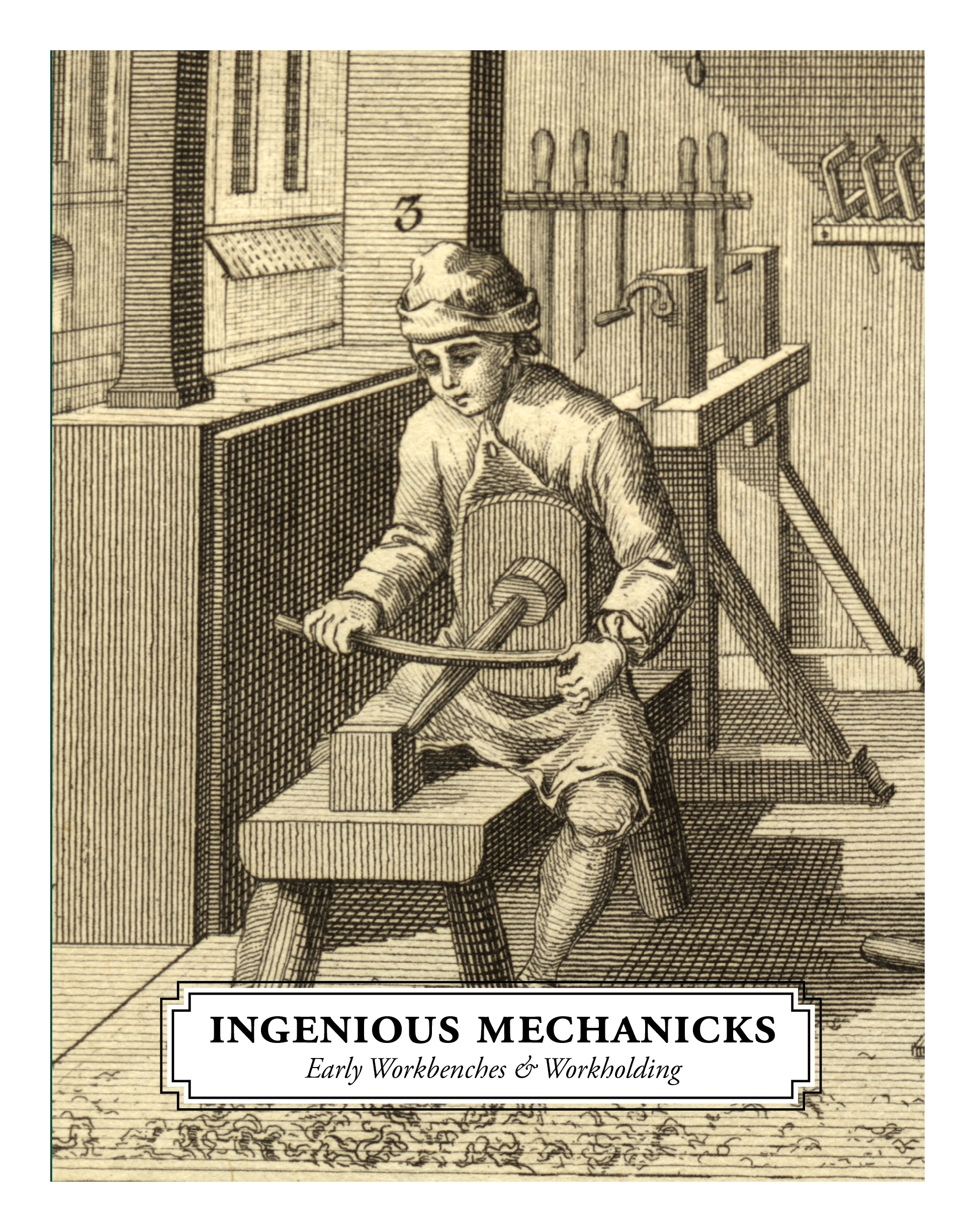

While sifting through bushels of old images for the research for “Ingenious Mechanicks,” Chris and I would often come across some odd something or other that made us scratch our heads. To give you a look behind the scenes, I’ll show you examples of how we verified a workholding device was real and not a figment of the artist’s imagination. The first two examples are not in the book and are some investigations I did on the side.

Grasping Limbs

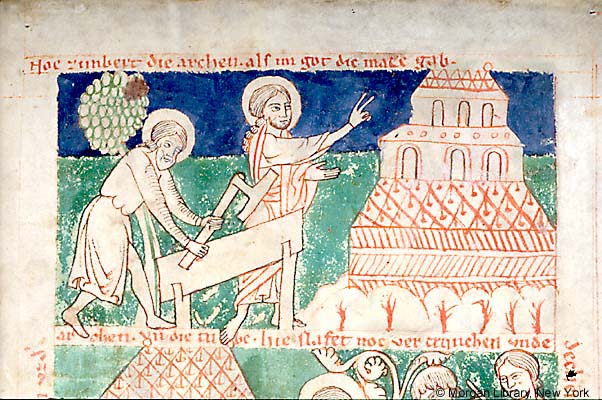

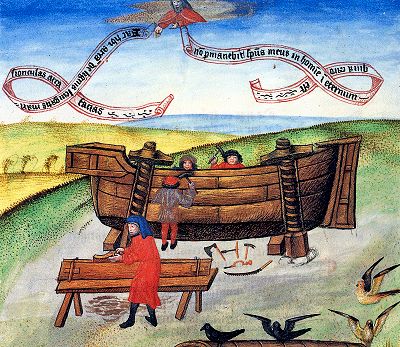

In the image above Noah is directing the building of the Ark. A board is held on two stands. I termed them “grasping limbs,” and Chris said it was a weird way to depict sawbenches. Plenty of images from the same time period showed four-legged sawbenches. Was this an anomaly? Could I find more images like this and, more importantly, find a description or photograph with the “limbs” in use?

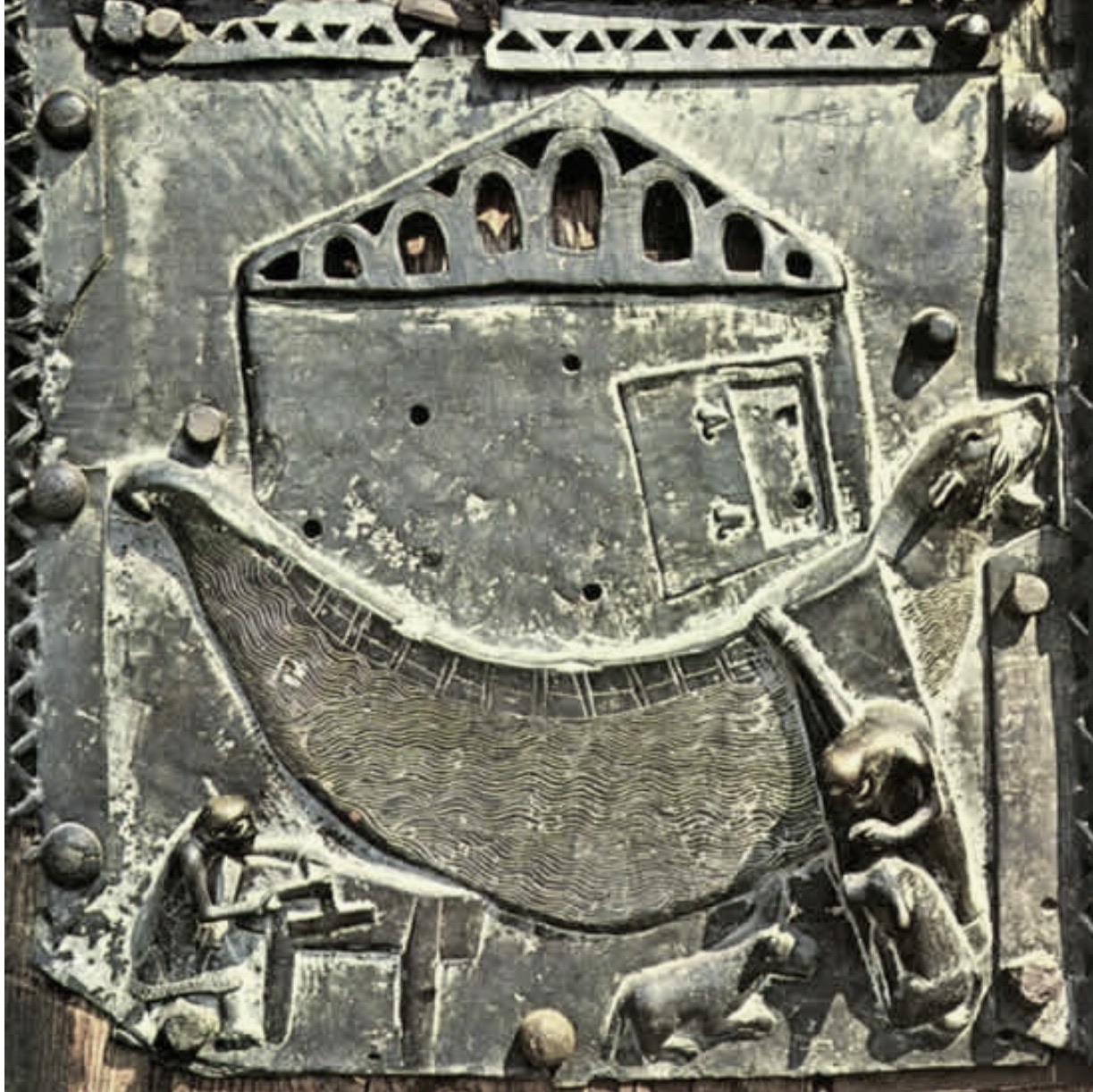

In fair Verona an even earlier example of the “grasping limbs” showed up in another scene of Noah’s Ark. But, more proof was needed.

In northern Burgundy the building of a 13th-century castle using traditional methods is underway. Here we see an actual example of the “grasping limbs.” They do exist.

Metallkrampe

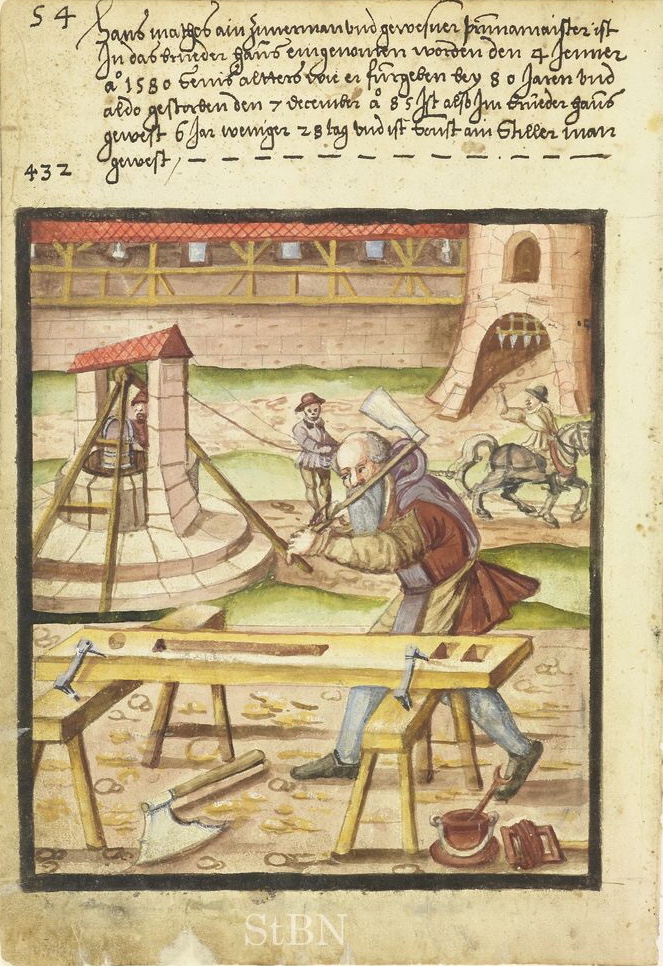

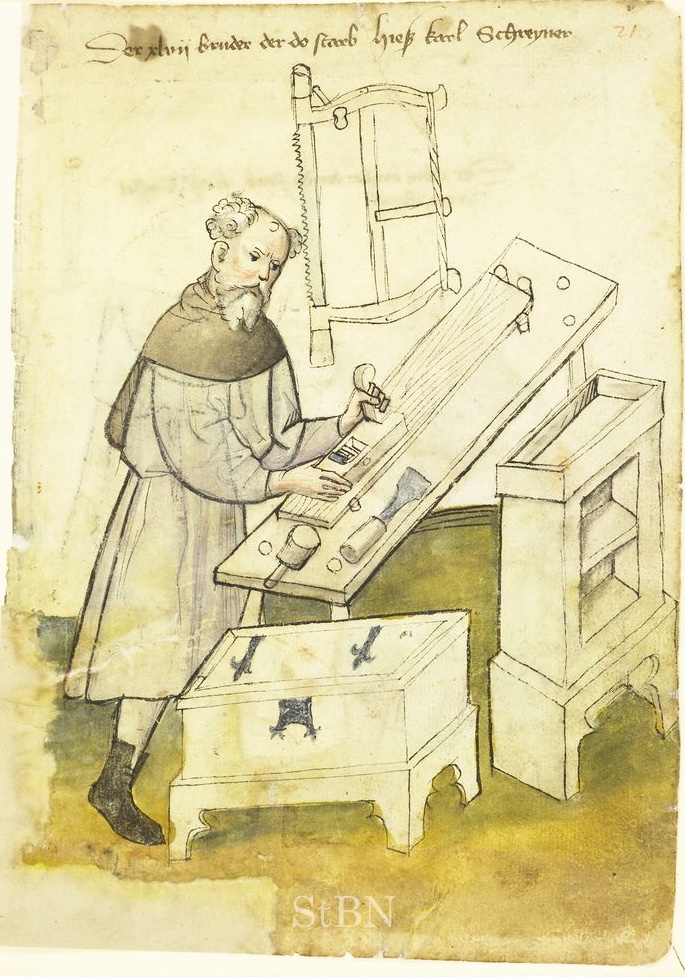

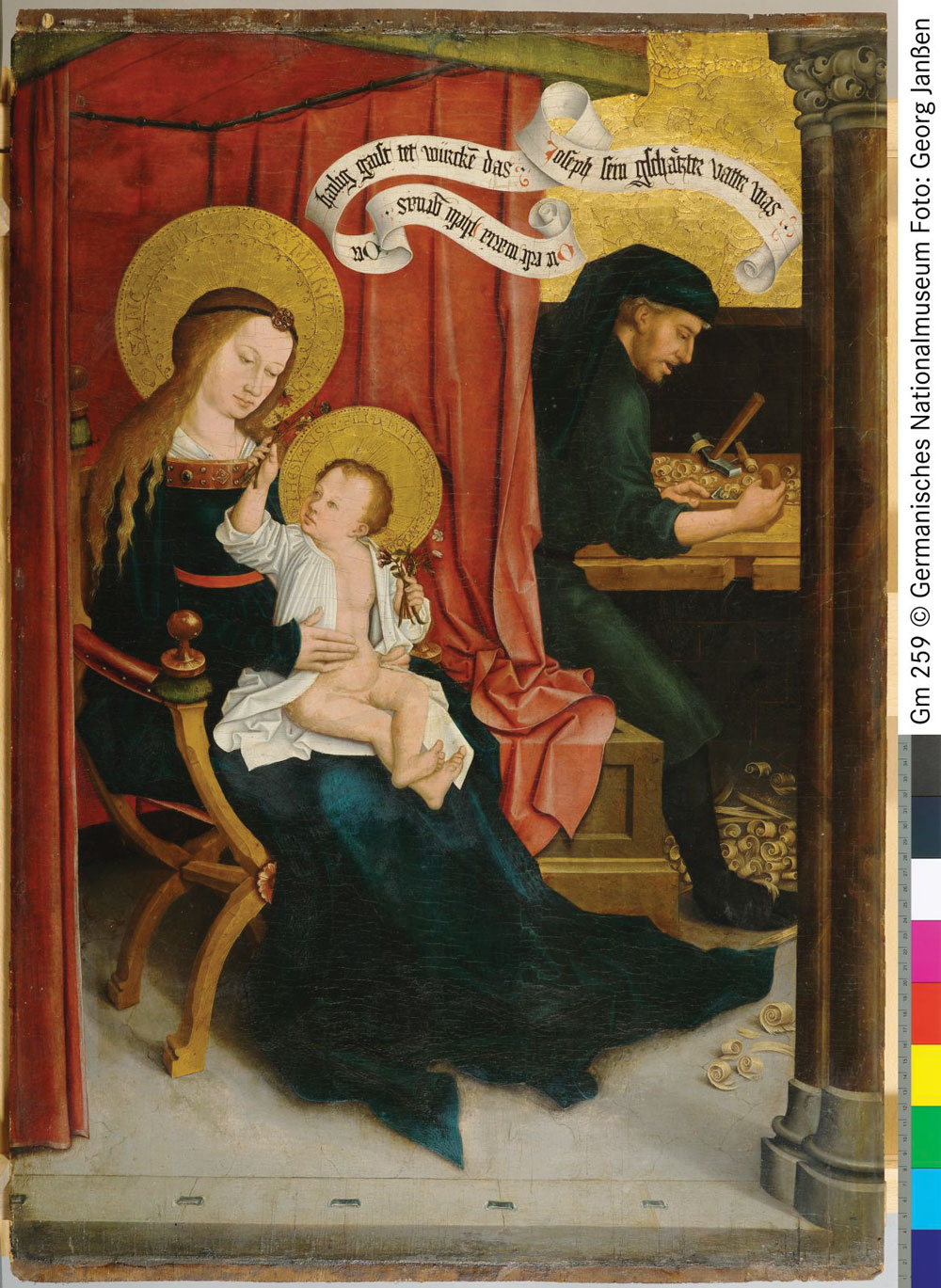

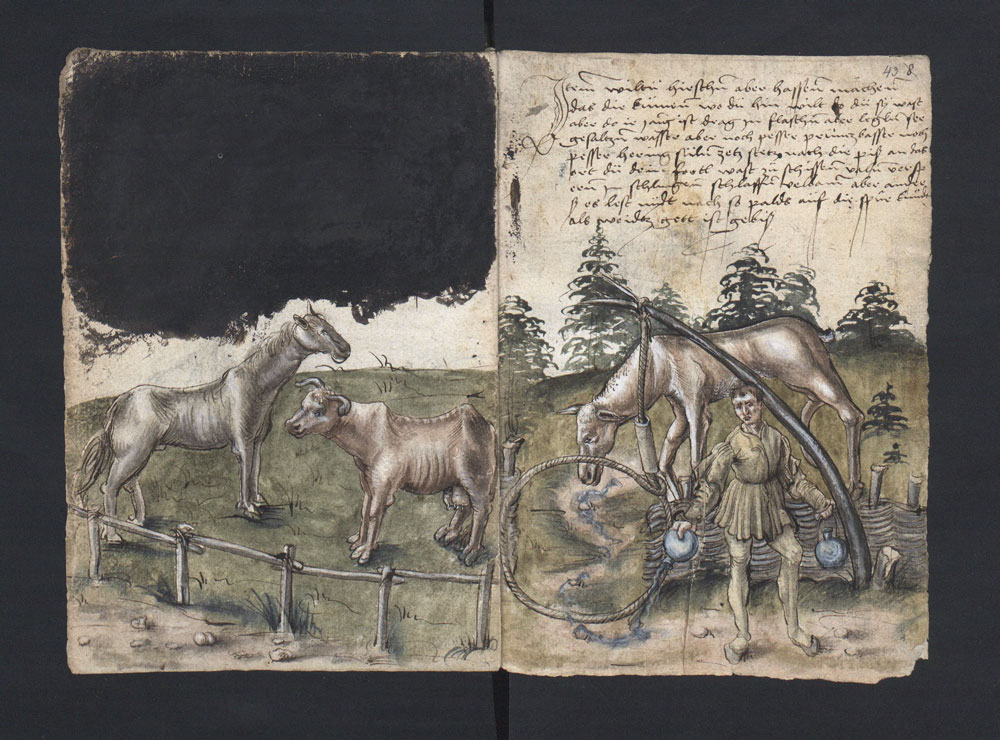

“Die Hausbücher der Nürnberger Zwölfbrüderstiftungen” are a rich source for learning about the work of 15th and 16th-century craftspeople. In several paintings there are carpenters using various means to secure wood to sawbenches or other supports.

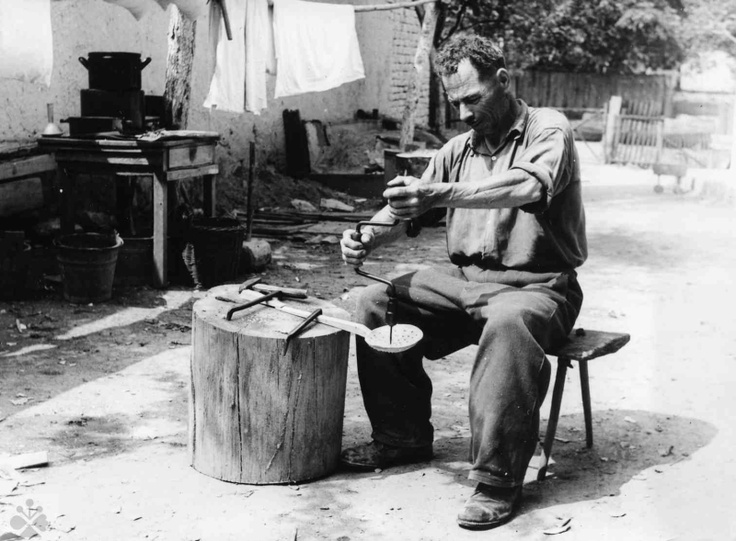

Brüder Hans prefers to use staked sawbenches for his work and is using sturdy metal kramps, or clamps for workholding. This makes sense for heavy work at a construction site. Were metal clamps such as this still in use several hundred years later and were they used by different crafts? Let’s go to Slovakia.

Here we have a spoon carver drilling holes in the bowl of a very large spoon. He is using metal clamps to hold the spoon in place. The photo is dated 1954. With a little more research I’m sure many more examples can be found.

The Way of the Peg

Using a combination of early 20th-century photographs, some help from the “Die Hausbücher der Nürnberger” and the Old Testament (plus try-outs in Chris’ workshop), the power of the peg as a workholding devise was revealed. Pegs are covered at length in the book, below is a small portion of the discussion.

“Woodworking in Estonia” provides valuable information on how carpenters worked on the low Roman-style workbench. Pegs at the end of the bench were a common method to use as a planing stop.

The “Schreyner pegs” were a key to using pegs as end and side stops on the workbench.

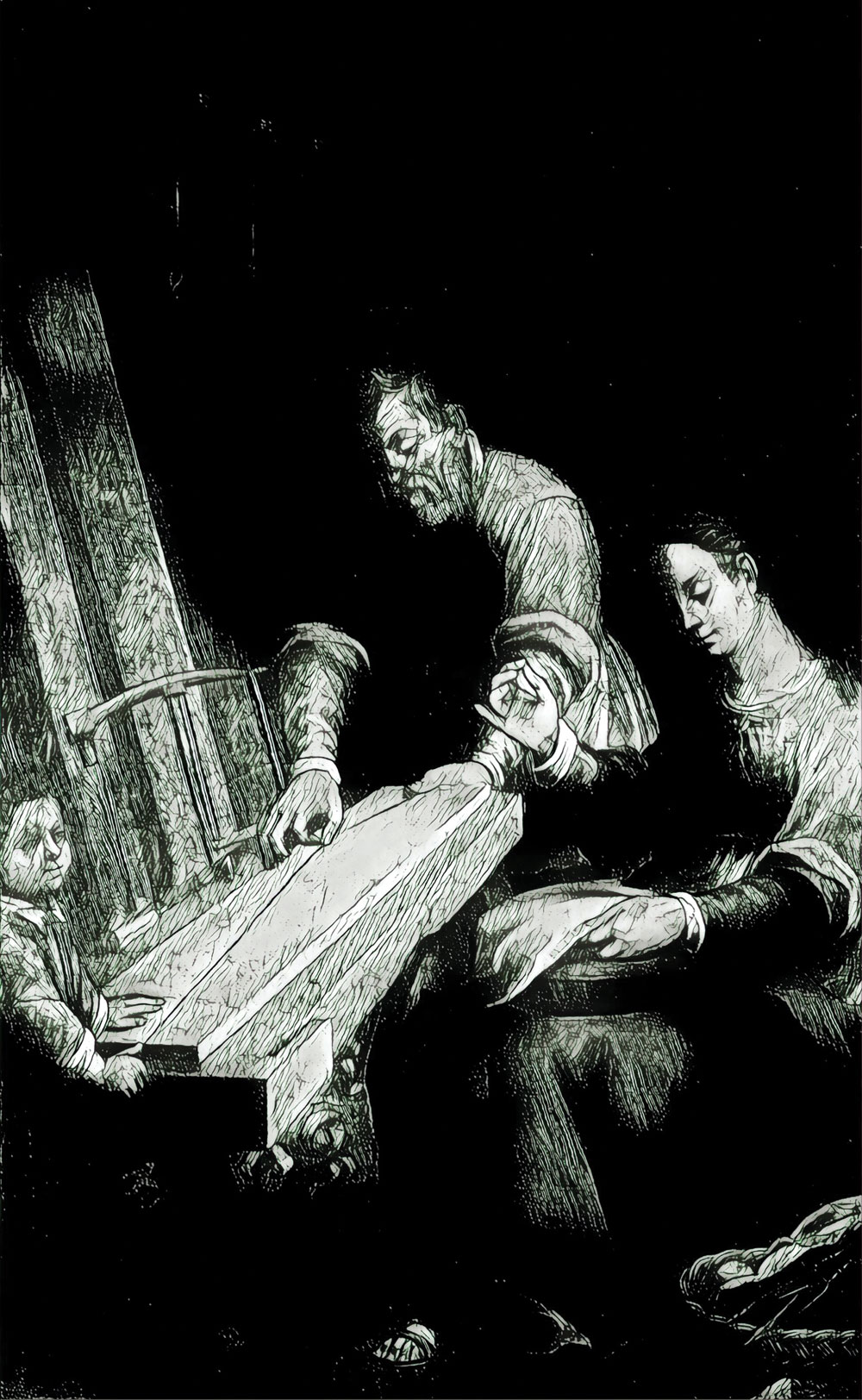

Moses guiding carpenters in the construction of an altar. The carpenter traverses a board with the pegs on two sawbenches serving as side stops. Using your sawbenches as auxiliary work surfaces to your low workbench is also featured in “Ingenious Mechanicks.”

A shot from Chris’ shop with end and side pegs securing a board on the low workbench.

A return trips to Estonia for edge-jointing a board. Adjust the height of the pegs to better hold the board. A peg at the end and pegs on either side hold the board in place.

And we are back to Noah. If there is a gap between the board and the side pegs, a wedge will take care of the problem.

When Chris was looking for the right space to create his workshop he mentioned one of his goals was to have a woodworking laboratory. He wanted a place to exchange and explore ideas on work methods and design. “Ingenious Mechanicks” is one product of that goal. It is also an invitation to other woodworkers to join the conversation.

In the next behind the scenes look I go looking for Saint Joseph; he isn’t always easy to find.

— Suzanne Ellison

Several customers have asked why they are receiving emails from our store notifying them that there is an updated pdf of “

Several customers have asked why they are receiving emails from our store notifying them that there is an updated pdf of “

You can now place a pre-publication order for “

You can now place a pre-publication order for “