It was a grueling week at the Appalachian Shangri-la as Michele and I spent more than 40 hours reviewing the page proofs of “Roubo on Furniture Making;” me reading aloud every jot and tittle (including punctuation and typography), while she followed along in my replica of the original French volume. It was a paradoxical sprint and marathon as we raced to review in minute detail each word, number and illustration of the new almost-450-page book. We stopped frequently to clarify the meaning or context of a word, phrase, or sometimes even a whole paragraph, leaving approximately a bazillion notations on the pages, mostly about capitalization and italics.

One thing is certain – it does reinforce the assertion that “l’Art du menuisier” was a work for the Ages and can serve as a vital part of any contemporary woodworker’s tutelage, now and for the conceivable future.

Consuming the entire manuscript in one stretch gave us, for the first time, the so-called “view from 40,000 feet.” And what a magnificent view it is! Not only did our appreciation grow through this high-altitude panorama, but we also began to notice subtle and not-so-subtle themes emerging, concepts and phrases we had not noticed before when we were focusing on much smaller units of the whole. This new appreciation was so affecting it provided us with the impetus to actually change the name of the book.

For our first volume, “Roubo on Marquetry,” I chose the lead portion of the title, “To Make As Perfectly As Possible,” from a phrase that Roubo used as exhortation throughout those sections of his original masterpiece. Never mind that it brought about perhaps the most unwieldy title of any woodworking book anywhere, ever. “To Make As Perfectly As Possible: Roubo on Marquetry” does not roll effortlessly off the tongue or the keyboard. Our expectation was that this lead phrase would serve equally well in the title for “Roubo on Furniture Making” and any subsequent volumes, which it would have done admirably, but after this week we are heading in a new rhetorical direction.

Throughout the often lengthy, detailed passages – and “Roubo on Furniture Making” is almost twice as long as “Roubo on Marquetry” – the Master invoked the sentiment and phrase, “with all the precision possible,” and we are eagerly purloining it as our own for this book.

So, I will be hand-delivering our marked-up copy of the proofs of “With All The Precision Possible: Roubo on Furniture Making” to Lost Art Press this coming Thursday at the Crucible Tool premier.

It still isn’t mellifluous but we like it.

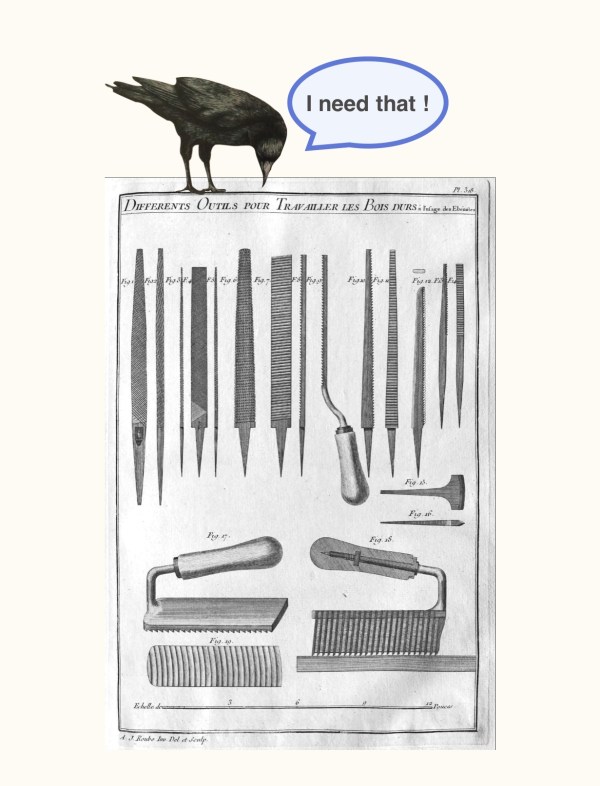

As I work on the index for “Roubo on Furniture” my appreciation for Monsieur Roubo continues to grow. Through the efforts of the translation team Roubo’s voice comes through and he certainly has opinions. Between explanations of how to use tools and make chairs, tables, desks and beds for all occasions he expresses his disdain for chairmakers and exasperation with carvers. Especially the carvers.

As I work on the index for “Roubo on Furniture” my appreciation for Monsieur Roubo continues to grow. Through the efforts of the translation team Roubo’s voice comes through and he certainly has opinions. Between explanations of how to use tools and make chairs, tables, desks and beds for all occasions he expresses his disdain for chairmakers and exasperation with carvers. Especially the carvers.