In his introduction to “Woodworking in Estonia” Mr. Peter Follansbee captured the spirit of this book when he wrote, “The products featured in the book are everyday items found in country households, combining utility and beauty in ways that speak volumes. This book shows us a culture that remained connected to its environment and its traditions long after some others had lost their way.”

An example of the Estonian craftsman’s knowledge of and relationship to wood is the use of naturally occuring shapes to make tools. Mr. Follansbee used the example of forked draw knives (hollowing knives): “A handle made this way follows the fibers of the tree, and it therefore stronger than one made by bending or joining straight sections of timber.” On the cover of the book is a gimlet made from a bough.

As Ants Viires describes it, “The gimlet, like other similar borers, was a tool which had to be applied with force, and it was equipped with an appropriate head that could be braced against the chest. Boring was hard work: “When you bored for some time, your chest bones gave out fire” (Pärnu-Jaagup)…When the work became too tiring, a small boy was placed astride the implement for weight…”

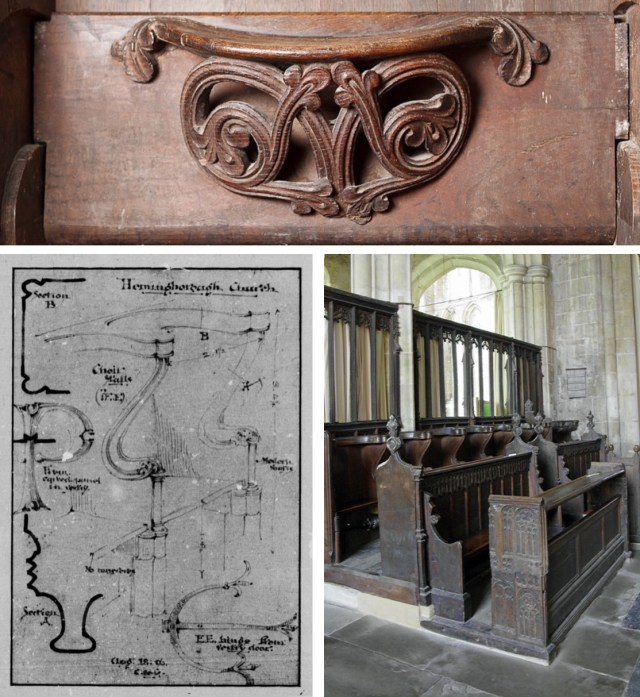

Some of the breast augers (or gimlets) in the top photo are made from branches and like the Estonian example several are carved with dates and initials. The Swedish augers range in size from 31 inches high by 19.5 inches wide to 18 inches high by 13.75 inches wide.

Other objects made from branches and roots that can be found in the book are boat ribs, wheel fellies and sled runners.

I recently showed my mother some of the sketches of Estonian tools made from branches and she reminded me of the slingshots my father used to make for her. When we lived in Fayetteville and Fort Bragg in North Carolina we had to be careful of the wild animals that might come into our backyards. Basking snakes and roaming snapping turtles were the most dangerous. My father used a forked branch to make the slingshot; the sling was cut from the inner tube of a tire. After some obligatory target practice (a tree was the target) my mother was a pretty good shot.

Once a particularly pugnacious (and big) snapping turtle arrived on the patio and was not intimidated by mother’s efforts with her slingshot. With me stranded on our picnic table my mother had to call my father to come home from the airfield and save me!

–Suzanne Ellison

Note: To clarify the use of auger and gimlet in this post here are excerpts from the section on boring tools in “Woodworking in Estonia.”

From Gimlets: ” Like all drills, the gimlet also consists of two parts: the iron and the head. The iron part is usually referred to simply as “auger,” while the head is known as “auger’s head.” On the islands it is called “auger’s handles.”

The gimlets made by early country smiths were of the bowl type (spoon borer). The characteristic veature of this implement was the bit, known as “kaha” (“kahv”) that is shaped like the spoon bowl and made possible boring in both directions.”

From Augers: “Under this term we refer to various borers differing in shape and size, the only common feature being a handlebar placed perpendicular to the top of the shaft. As such the borers are the simplest turning device, which was probably the starting point for the creation of a more complicated gimlet.”

And from Ants Viires’ summary of boring tools: “At the beginning of the millennium, certain borers were already in use in the country. The most primitive was the awl, which was often used after heating. The spoon-shaped borers of the gimlet or auger type were also fairly widespread.”

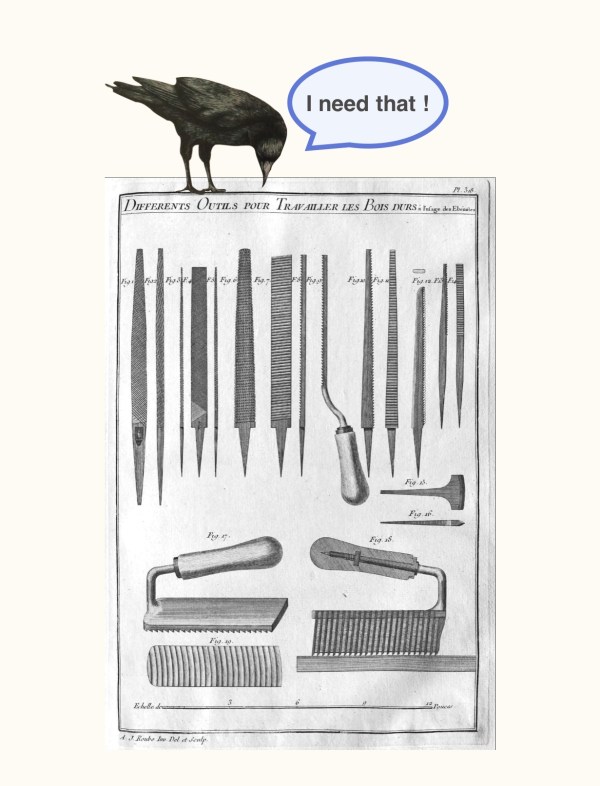

As I work on the index for “Roubo on Furniture” my appreciation for Monsieur Roubo continues to grow. Through the efforts of the translation team Roubo’s voice comes through and he certainly has opinions. Between explanations of how to use tools and make chairs, tables, desks and beds for all occasions he expresses his disdain for chairmakers and exasperation with carvers. Especially the carvers.

As I work on the index for “Roubo on Furniture” my appreciation for Monsieur Roubo continues to grow. Through the efforts of the translation team Roubo’s voice comes through and he certainly has opinions. Between explanations of how to use tools and make chairs, tables, desks and beds for all occasions he expresses his disdain for chairmakers and exasperation with carvers. Especially the carvers.