We’re so hard-core at Lost Art Press that our first question to accountant candidates was “are you a woodworker?” OK – not really. But it turns out our accountant really does spend a fair amount of time in the shop! That’s his work shown above, and he wrote the below.

– Fitz

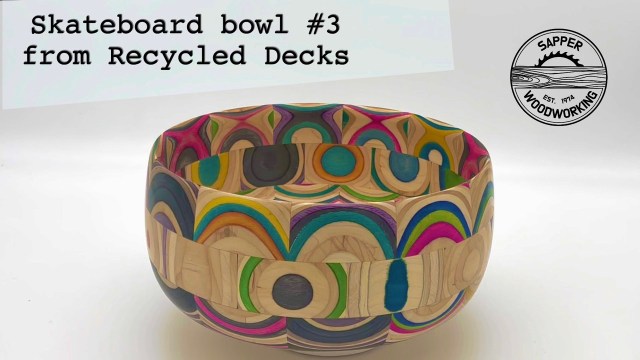

The first question is always “how long did it take to make that?” I pondered the question for a few moments and answered “well, I started this bowl in 1977.” While it didn’t actually take me 45 years to make the Rainbow Bowl (from recycled skateboard decks), it’s certainly the result of an early life passion for everything skateboarding.

In 1977 I was 13 years old and my family had recently moved to a new neighborhood where hundreds of homes were to be built in the next several years. Where others saw a burgeoning neighborhood, I saw an unlimited supply of scrap construction lumber perfect for making skateboard ramps and jumps. This might where my lifelong woodworking hobby found me. It could have started out by simply nailing a piece of plywood to a 2×4 to make a basic skateboard ramp. I don’t really know for sure where it started, but I’ve been making things from wood since as long as I can remember.

Fast forward 45 years and I have a house full of personally handcrafted treasures, from a large kitchen table, to a dining room buffet, to lamps to shelves full of what a friend calls “dustables,” and of course a growing number of turned bowls.

As a woodworker, it wasn’t a secret to me that skateboard decks are made from high quality laminated maple hardwood ply, often with the layers dyed in random bright colors. And I’m most definitely not the first woodturner to use skateboard decks in their projects. YouTube has no shortage of videos with folks making all sorts of things out of skateboard wood. My first skateboard project was using old skate decks from a friend’s son to help her create a table and bowl. These were both gifted back to her son. I was pretty happy with how those projects turned out, so with the first pile of used skate decks I was able to acquire, I set my sights on making something unique and colorful.

One of the challenges in woodworking with skateboard decks is that, counter to what you might think, nowhere on the board is actually flat. The board’s ends curve up to serve up as kick tails and the center section is concave. This usually results in troubles gluing the layers together. While ripping a deck board into thinner strips, it occurred to me that regluing those thinner strips into a stack would be perfect working material for a segmented (or wedgies) style bowl. So that’s the direction I went, creating what is now known as the Rainbow Bowl. I filmed the video below that illustrates the process of making recycled old decks into a pretty cool decorative piece. I’m really proud of this piece, and as far as I can tell, it’s a unique take on using this very colorful raw material.

– Mike Sapper

P.S. Please visit my YouTube channel to leave questions/comments on this video – and subscribe to keep updated on future projects, which will include charity events and bowl giveaways.