The following is excerpted from “James Krenov: Leave Fingerprints,” by Brendan Bernhardt Gaffney.

After years of research and more than 150 interviews, Gaffney produced a definitive biography of Krenov, featuring historical documents, press clippings and hundreds of historical photographs. Gaffney traced Krenov’s life from his birth in a small village in far-flung Russia, to China, Seattle, Alaska, Sweden and finally to Northern California where he founded the College of the Redwoods Fine Woodworking Program (now The Krenov School). The book brims with the details of Krenov’s life that, until now, were known only to close friends and family.

And we, who leave our offices and factories to spend a few days – or weeks – outdoors, what is it that we seek? Each of us has his or her answer. Not everyone wants to – or can – really “get away from it all” during any great length of time. Nor can we easily adopt a mode of living from which materialism is isolating us. Yet for the majority of us there exists this fact: by discovering for ourselves a blossom, or a drop of dew, or through sailing, fishing, climbing, skiing – or by just walking in the sun, we tap a new source of life. Partaking of it, we become more vigorous, confident and happy, more at peace with ourselves. Our mind and body are restored. In nature, free and waiting, is something fine and enduring, to which money and high-pressure entertainment can never bring us. The harder the way to it, the more of ourselves we have to give, the more skill, strength, will and understanding we put into the search – the greater our final reward.

– An excerpt from an unpublished short story “For The Asking,” by James Krenov, written in March 1951.

[James] Krenov and his mother [Julia] arrived in Sweden in the winter of 1947-48, on the next leg of their life’s continued adventure. Sweden had maintained neutrality throughout World War II, and was relatively unscathed compared to the neighboring continental countries, which were still in a state of Allied occupation and reconstruction. Krenov’s passport bears a number of stamps from Norway, Occupied Denmark and Occupied Germany in his first year in Sweden; whatever stability he had in Seattle was soon traded for a renewed sense of adventure and independence in Europe.

“The war over, it was inevitable that I should go to Europe,” Krenov later wrote in “A Cabinetmaker’s Notebook.” “I come from a family of restless people.”

Krenov’s friends at the Port of Seattle had told him that it was easy to find work in Sweden; after a short time around the continent, Krenov found work in a factory. Sweden’s factories were a melting pot at the time – thousands of refugees had fled the continent and the strife of war-torn Europe for the stability of Sweden and its steady economy. Many of Krenov’s coworkers, especially those from Poland and Czechoslovakia, were awaiting visas to the United States. Krenov would later call the environment “memorable,” with a great degree of optimism and hope among his company of “peasants, professors, doctors, and common thieves” from the continent. Many were alone, some had come from the concentration camps of Nazi Germany and a majority had suffered as soldiers or prisoners of the conflict.

While he enjoyed the diversity of his coworkers and the “camaraderie that transcended the petty little rivalries and touches of nationalism or exaggerated patriotism,” the work was physically exhausting. The work was grueling and wore on the 28-year-old – he came to resent the “pace, the atmosphere, the lighting, everything.”

He knew, perhaps through his father’s experiences, that he could not survive a long-term jaunt in the factories, but the shortage of labor meant that Krenov could work through the long winters at various factories making “electrical equipment, radios, and neon-light fixtures,” and in the summers, he could venture from the city to the expanse of northern Scandinavia and the continent being rebuilt to the south. He would recall making enough money in his winters at the factories that he could take a “princely vacation” for a month or two and return to the factories in the autumn to work.

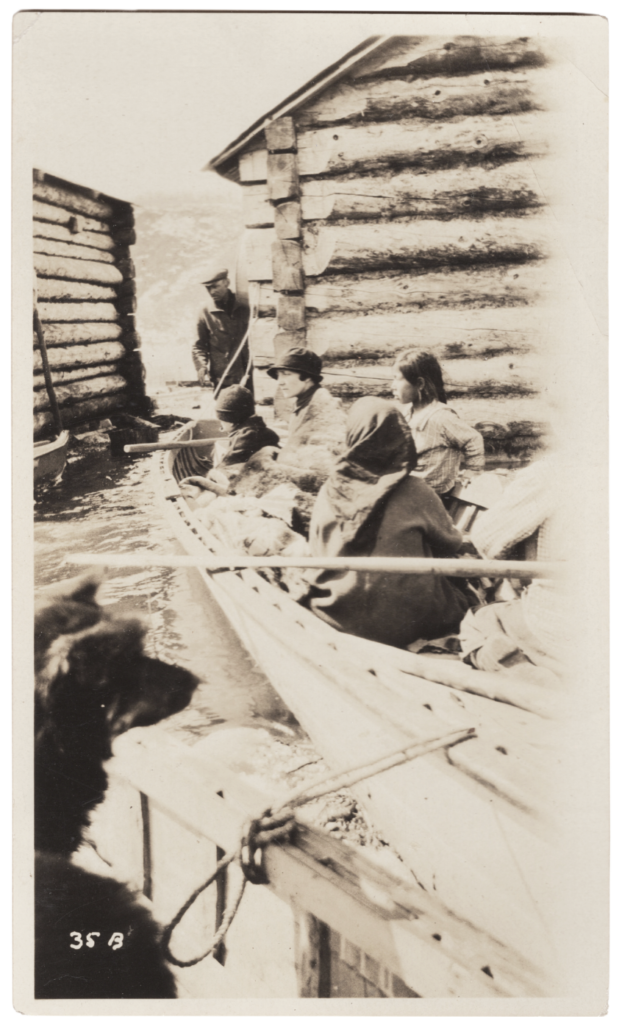

Krenov’s adventures in the summertime brought him to the remote northern reaches of Scandinavia, an environment not unlike that of the Taiga his father had so loved and the Arctic of his youth. His descriptions of remote Norway and Sweden also take on a language distinctly similar to that of his mother’s own writings of Siberia and Alaska.

“When in summertime I tramped the hills of Härjedalen, I felt an affinity, a ONENESS with them,” he wrote in “The Searching Soul,” one of the travelogues he wrote in the late 1940s. “I lost myself in the peace and harmony for which they stood. What I experienced was simple, earthly, warm.”

Following in his parents’ footsteps, Krenov developed a fascination with the mountainous isolation of Scandinavia. And, like Julia, Krenov took to writing about these jaunts into the north. He would write dozens of vignettes over his first few years in Sweden, in “fictional” stories that sometimes switched the name of the narrator of the story but were autobiographical. Hundreds of miles north of Stockholm, he would encounter something akin to the Siberian and Alaskan north that had so deeply impacted his mother’s life and set the stage for his own.

This new character he inhabited in the summer, that of a traveler and documentarian, was no doubt deeply influenced by his mother, herself a self-described “adventurer” and writer. There is little doubt his mother encouraged his exploits, as they lived together during his first years in Sweden, and his writings would even come to describe the native peoples he met in the remote northern reaches much like his mother’s. Krenov encountered the “Lapps” (the indigenous Sámi people) on his backpacking adventures, and documented their stories and mannerisms in an anthropological manner similar to his mother’s. Krenov’s travels north also showcased his self-sufficiency and deep-seated sense of adventure.

“After a few summers I knew a large area of that part of northern Sweden,” he wrote years later. “I knew where there were places one could seek shelter if the weather was bad; where there were fish; where I could meet reindeer herders who, even if they were not my friends in the sense of sharing an occupation, were friendly and understanding of anyone who walked as I did.”

Krenov would continue these northern adventures into the 1950s. In subsequent years, he would return frequently to a small hut in Härjedalen with his young family, introducing them to the wild north just as his father and mother had done with him – though, in this case, there was no threat of revolution or war nipping at his heels.

In addition to these northern escapades, Krenov also made summer trips to continental Europe, where he encountered the strife and difficulties of war that he had first heard of from the sailors in the Port of Seattle. His passport shows an early trip through occupied northern Europe and into France only a few months after his arrival in Sweden in 1948, and in subsequent years he would travel through Germany, France, Italy and many other countries in between, by boat, rail, bicycle and on foot.

These trips were seemingly motivated less by the excitement of the frontier instilled in him by his childhood in the Arctic but more so in pursuit of the culture and experiences of his mother’s youth some 40 years earlier. Where his mother would detail the operas, ballets and refined culture of the continent in her memoirs, Krenov became enraptured by the architecture, the people and complex political situation of a post-war Europe. Some of Krenov’s friends from Sweden would recall later that he and his mother had initially come to Europe in search of something Julia had lost when she first fled to Siberia, be that the refinement, culture or a sense of old-world belonging. What they found was not the continent Julia had left, but it was a world that fascinated her son.

During this early time in Sweden, Julia settled into life as an expatriate. She again found work as a teacher and language tutor, helping a number of distinguished expatriates learn English and French, two languages in high demand in post-war Europe. While she may not have found the aristocracy of her youth, she did settle into a life in the company of diplomats and the upper-class. Poor though she was, her abilities with languages made her a valuable person in the increasingly affluent and worldly Swedish city of Stockholm, and it would be her lifeline and income for the rest of her life. Her granddaughter, Katya, would later recall a visit she took with Julia to the apartment of a diplomat – the company drank plum brandy and had conversations in the luxurious Stockholm apartment. Julia would also take Krenov and later her granddaughter to all manner of ballets, operas and traveling cultural events that would pass through Stockholm.

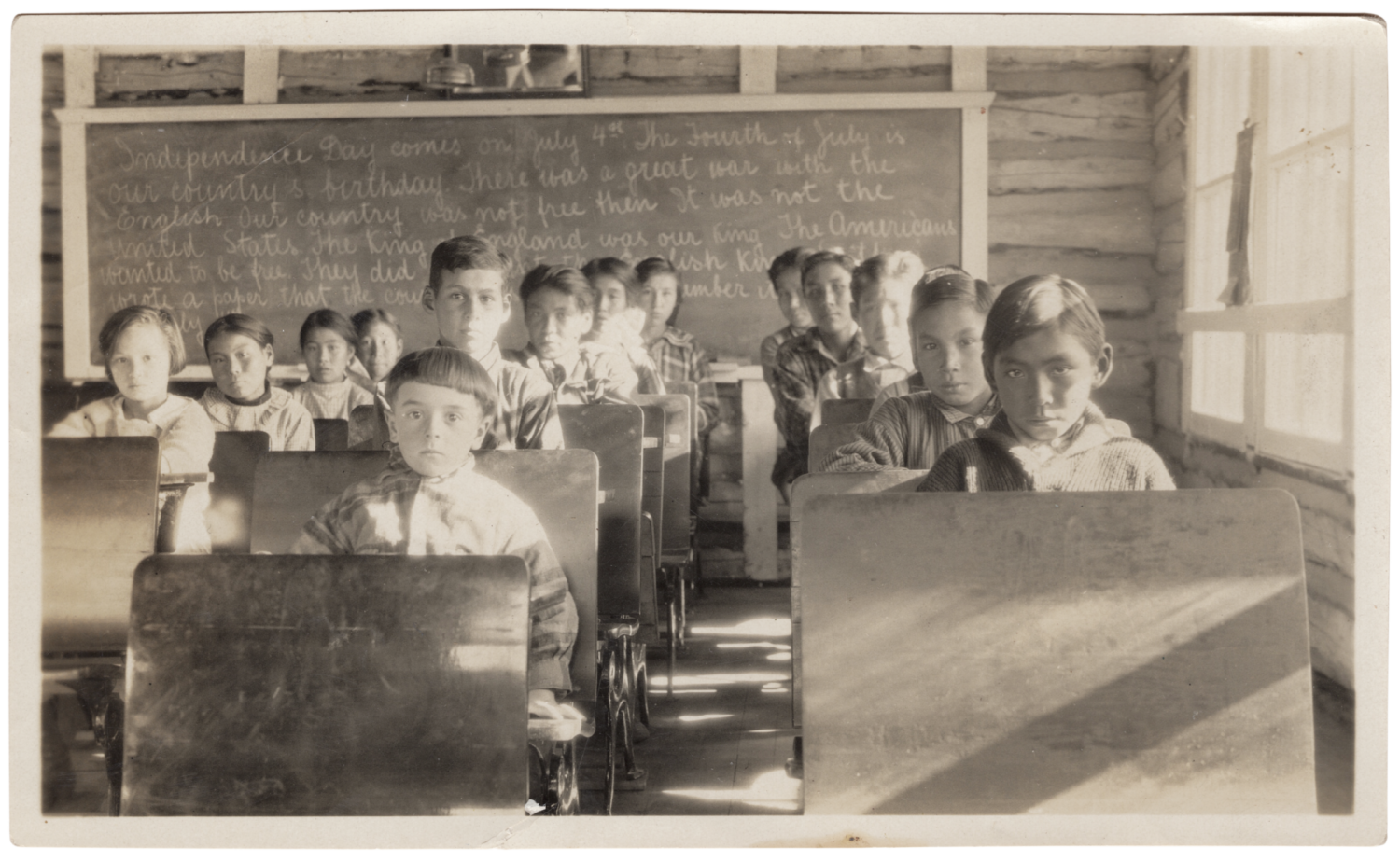

Julia did have some success with her writing in 1951. After two decades of letters and sending manuscripts to publishers, she managed to get a portion of her transcribed legends published in 1951 in the Journal de la Société des Américanistes, a French academic journal of cultural anthropology in the Americas. While a small success, her memoir did not see the same results; Krenov later remembered trips with her to various publishers in the years that followed, hoping to have her longer writings published. Her failure to publish the memoir was clearly a disappointment and may have further provoked her urging for her son to write and publish his own stories.

Like his writings about the northern reaches of Scandinavia, Krenov again fashioned his stories about continental Europe as both travelogue and fiction. While his short stories concerning the north revolved around the remoteness and humbling presence of a harsh natural world, his writings of France, Italy and the continent focused more on the people and how he related with their lives, struggles and humanity.

Krenov made a determined play at having his writings published, and starting in 1949, he began sending stories to publishers in Stockholm, Paris and elsewhere. Among his papers, a number of the stories written in this period bear stamps and notes for publishers in Sweden. These documents, which also bear return addresses, dates and some biographical references, also provide the backbone for what little primary source information can be found for Krenov’s first years in Sweden.

The stories Krenov worked at having published covered a swath of his own adventures in his first three decades. “The Bridge,” a short story about the Tacoma Narrows Bridge Collapse in 1940 that Krenov witnessed firsthand, was among the stories sent for publication. Others included “The Lapp,” a short story about a Sámi native man who Krenov met in his travels north; “Searching Soul,” a travelogue about the deep wilderness of Sweden; “Forgotten Stones,” a story about an indigenous man leading a settler to a hidden mine in remote Alaska; and other such stories that followed his biographic arc.

He did see some early success in getting his work published. Dagens Nyheter, a Swedish newspaper based in Stockholm, published five stories from 1950 to 1955. The first was a collection of three Alaskan fables, presumably ones he had borrowed from his mother’s collection of translated fables, which appeared on Aug. 27, 1950. The subsequent four stories were his own travelogues, written about northern Sweden and the European continent. In a short biographical blurb in the travelogue of his northern trip, Krenov is described as “a young American, in love with Härjedalen’s mountain world … he felt as close to home as you can in foreign lands. His hometown is Seattle, and he spent seven years of his childhood in southern and inner Alaska – hence his home feeling in Härjedalen.” This short bio draws the clear connection to his time in Alaska and northern Sweden, drawn in his own words.

Over the course of these writings from his 20s and 30s, Krenov’s tone shifted from poetic travelogues and short fiction stories to a decidedly more idealistic and philosophic set of stories about the strife and challenge of European life. Krenov not only recalls with great detail the characters and places he encountered but what he saw as the ailments of the industrial society. In “Italiensk Resa” (Italian Journey) written in 1953, he mourned the overworked lower-classes and made a reproach of the dehumanizing force of capitalistic pursuits. His shift in tone reflected both his difficult time working in the factories and the beginnings of his own personal soul-searching, a philosophy that cast off “productivity” for emotional and holistic pursuits. He would continue to develop and pursue this theme for the next several decades, through to the publication of his first book on the subject of furniture making two decades later.

One of the first countries Krenov visited as a traveler was France, in the summer of 1949.

“In France, he had known elation and a sort of mental sharing,” Krenov wrote in 1953. “But life there was not for him; he could not become a part of it. They knew too much, the French. And knowing too much, they believed in very little – hardly anything, really, except their right to disbelieve. Michael could not stay in France. He liked the people, their wit and verve … but something within him shrank from so much wishing – and so little doing.”

While he found no home among the French, this trip altered the trajectory of Krenov’s life. It was a chance meeting at a café with a Swedish woman two years his junior, Britta Lindgren, that would change his course and anchor him to Sweden and a quieter life. Britta would become his companion and dedicated partner for the next 60 years.