I posted this at my blog but am sharing it here because it’s the best way I know of to thank those who contributed to the fundraiser Megan organized on my behalf last week. A Little Acorn will show up at your Inbox next weekend, and it’s going to be a fun one!

When Megan Fitzpatrick mentioned that several people last Saturday had asked if there was any way they could help, given my current experience with pancreatic cancer, she suggested she could put together a fundraiser for medical expenses. I was touched – truly – both by readers’ offers of help, and by Megan’s readiness to set something up. But I had to give some thought to my response.

Asking for help is not one of my strengths. Even accepting help that’s offered is sometimes hard. I recognize the importance of reciprocity. It’s great to be one of those people who give and give and give, but you can only give if others are willing to receive. And at some point, those who are unwilling to receive are missing out on a good chunk of what life is about. So I am trying, believe me (and please don’t say, as my first husband used to, “very trying”).

Second, while I often contribute to fundraisers, I find the whole fundraiser thing a challenge sometimes. Who wants to be seen as needy, or a victim? I know; this is another problem I have to deal with (one of many). Asking for help, or accepting it, does not a victim make. But some people have given online fundraisers a bad name. And the idea that many people in America rely on fundraisers to cover the cost of life-saving medical care drives me nuts. I lived in England for 16 years, and while the National Health Service was (and remains) far from perfect, single-payer healthcare beats the heck out of potentially losing your home due to medical expenses. Also, it’s not news that the American healthcare system, too, while technologically awe-inspiring and peopled with professionals who are the embodiment of patient-centered service, falls far short of ideal, especially in its financial dimensions.

Finally, it’s not news that we’re in the midst of a raging pandemic that has cost millions of people their livelihoods. Yes, I have cancer, but all in all, Mark and I are in better shape than many, with paying work that each of us can do safely during this time, which added to my difficulty in saying “yes, thank you, let’s do it!”

I want to make sure people know that Mark and I have health insurance. While we have friends who don’t, both of us have made a point of paying for coverage since long before we even knew each other. As I explain in an upcoming blog post for the Pro’s Corner at Fine Woodworking, I bought my first health insurance policy in 1995 when I saw how much a client of mine, who had excellent healthcare coverage, had to pay out of pocket to fix his broken foot. His out-of-pocket expenses could well have put my then-new business out of commission, and we all know that those who work in the building trades are at higher risk for work-related injuries than most who work in offices.

Mark and I are both self-employed. Paying the health insurance premiums has often been a stretch, especially for me, but we’ve considered it no less important than paying our mortgage. Finding the right balance between affordable premiums (if $845 a month per person can be described as “affordable”) and coverage in case of a claim has also been a challenge. Like many of our self-employed friends, we chose our policy, paid the premiums and hoped we’d never have to use it, beyond the reductions it provides in charges for prescriptions, wellness scans and such. As it turns out, our high-deductible HSA-linked family policy will cost us $24,800 this year in out-of-pocket expenses before our “coverage” kicks in. Yes, just having insurance coverage is an enormous help – as we’re now learning, the basic charges for anesthesia, chemo and all sorts of related care are astronomical. But in a year when our income will already be seriously reduced due to changes we’ve made in how we work, thanks to the pandemic, forking out $25,000 (or, let’s be realistic, likely more) would hit us hard. Were we not living in Covid World, things would be at least somewhat different – I wouldn’t hesitate to take friends up on their offers of rides to the hospital, and Mark could be working more closely to normal. But with a significantly compromised immune system, it would be foolish for me to get in a car with anyone else, which has disrupted Mark’s work far more than we anticipated. In fact, it would be more than foolish. It would be irresponsible and ungrateful, considering how many people have already helped us out.

After mulling all of this over, I said yes to Megan’s generous offer of help. I had no idea how many people would respond, nor how quickly. I’m still in shock.

To each of you who have contributed, I am grateful. My gratitude is not just a feeling. I plan to express it concretely, in the following ways, as well as others:

First, I promise to do my level best to beat this disease. Life expectancy for those with pancreatic cancer is depressingly low, with two years generally cited as the outer limit. But every week, friends introduce me to others who have lived much longer. Of course, prognoses depend on all sorts of variables; as people tell me constantly, every tumor is different, and the side effects of treatment can also kill you. Beating the odds will take more than standard medical care, and your generosity will make it possible for me to augment the standard chemotherapy, etc. with integrative protocols. While these cost far less than the medical “standard of care,” they are not covered by insurance. Even before the last 24 hours I was feeling optimistic. Now I feel even more so.

Second, I will share everything I learn, in the hope that this information may be helpful to others. Hence my upcoming post about the importance of being informed when choosing health insurance coverage.

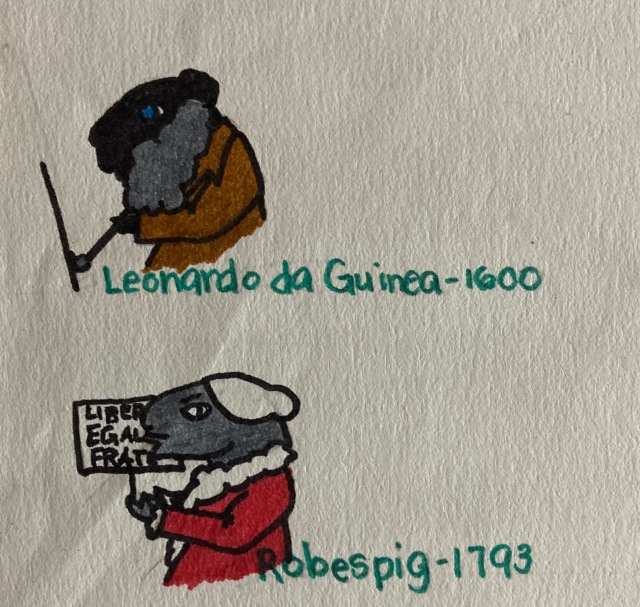

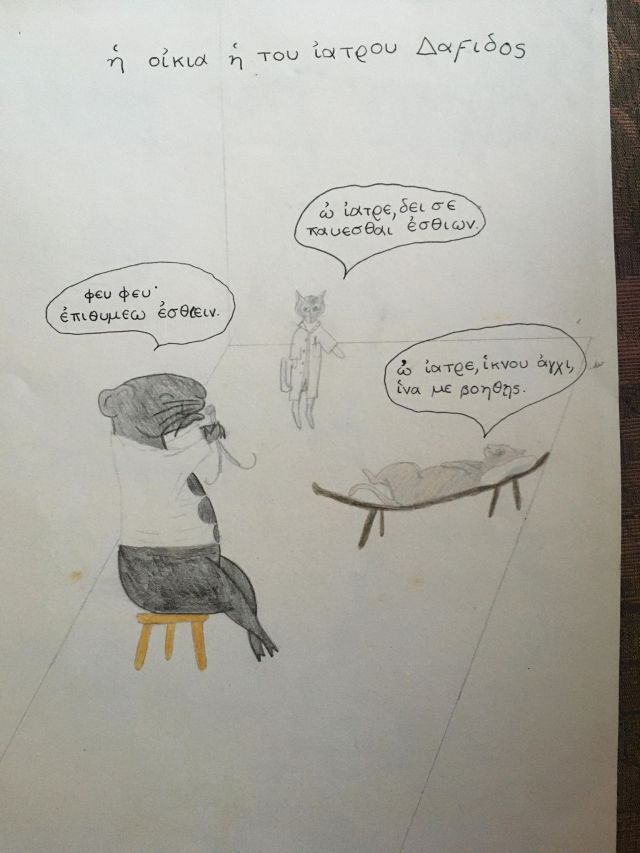

Third, I’m hard at work on “Shop Tails,” a new book for Lost Art Press. I didn’t want to mention this early on, as I had no idea whether I would live long enough to finish it – in late-November, the specialist in Indianapolis had given me four to six months if I didn’t pursue chemotherapy, adding that there are two chemo regimens, and fewer than 50 percent of pancreatic cancer tumors respond to either one. Crushing odds. When I was struggling with the decision whether to pursue chemo (for so many reasons, the cost and the odds among them), I realized that if I went ahead, I would need a concrete goal to power me through. I wrote to Chris Schwarz on a Saturday morning, asking whether he might be interested in publishing a book about animals, life and work. I made sure to include a note along the lines of It’s fine to say no. This is not “Give me a contract or I’m going to die.” He wrote back with a strong YES that afternoon. Another reason why I am filled with gratitude — and having a far better time right now than I would ever have expected.

So, for now, thank you. Your support has me feeling far more appreciated than I had any reason to imagine. I am endlessly grateful to Megan, Chris and all the others – editors, publishers, clients, relatives, friends – who have provided me opportunities to do work I find meaningful.

–Nancy Hiller, author of “Making Things Work” and “Kitchen Think“