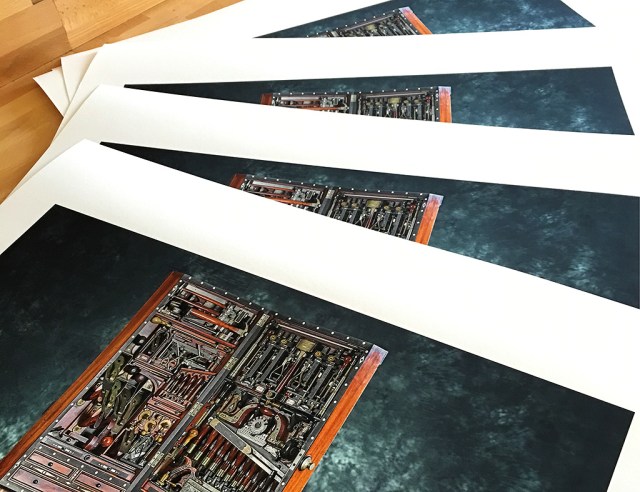

At last year’s H. O. Studley exhibit in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, I offered a limited edition art print of the H. O. Studley tool cabinet and workbench. Due to time constraints in the weeks prior to the exhibit, I was only able to produce 82 of the 100 prints in the edition. Those that were for sale sold out in two days, including the framed print I intended to use as a display piece then keep for myself.

This particular image does not appear in the book; the one we used on an opening spread features an empty tool cabinet and moodier lighting. I arranged the lighting for this particular photo with a yearbook or school photo in mind and refer to the image as the “yearbook photo.” I wanted an image that presented the ensemble elegantly but honestly, without drama — a portrait. When people see this print they usually describe it as “amazing” or “incredible” and though I agree wholeheartedly with those comments, the image evokes different feelings for me. This particular image usually makes me smile in the same way that school photos of my children make me smile. Perhaps because this was one of the last photographs we took in the four-year project of documenting these objects, and as such the image captures a period of time in the same way that the annual school photos do. But also because after working with the photo as much as I have in the last year, I revel in the tiniest of tiny details that I discovered when processing the image, like the grain of the workbench or the legible numbers on the wire gauge or the fact that if you look closely, you can see the felt we used underneath the cabinet to protect the workbench top.

Details such as these are present in the print because as an art print, this edition is as close to flawless as I can get. The photo was taken with a 37 megapixel camera rented specifically for special shots like the front cover and other images intended for large-format reproduction. The image file is 450 megabytes and has been painstakingly optimized for output on one of the finest archival art papers made, Hahnemühle Photo Rag — a 100 percent cotton paper with a weight of 308 gsm. My professional-grade printer uses 12 inks (normal presses use four), which produce an image with subtleties you’d never get on a printing press. And though my printer can produce about five of these prints in one hour, it can take 30 hours or more for a final product to be ready. I let each print rest at least 24 hours before checking it for scratches and printer errors. If all is well with the print, I proceed with hand numbering and signing (a process that has yielded many “artist’s proofs” — my hand can’t keep up with my brain and I end up botching the title or print number over and over), then spray the print with a protective spray which fixes the ink and makes the print a bit more abrasion-resistant. The print then dries for another few hours, after which it is placed in an archival plastic bag with some instructions for taking care of the print.

There are only 18 of these prints left in the edition, and I’m finishing up production work on them now. They will cost $100 each as they did at the exhibit, though for these last prints I’m including a large-diameter art tube and will ship them to you via FedEx at cost (domestic addresses only). If you are attending the LAP open house in Covington, Ky., in March, I’ll bring yours there to hand to you personally. Here’s how this is going to work:

- Starting at 9 a.m. CST on Monday, Feb. 29, interested parties can send an email to studleyartprint@amoebr.io. In this email you should provide your full name and address (if you’re picking up your print in Covington, just type “Covington”). The reply address for your mail should be valid; if you have an email address you’d like me to use for a PayPal invoice, please specify that as well. No need to write a note or anything – just the above information is fine.

- Don’t send an email beforehand; the email address won’t work until the time specified above. If you’re a friend who can contact me through other channels, I’d love to “hook you up” with a print but I won’t — I’d like everyone to have an equal chance at these last prints.

- I will turn off the email address after I receive mails from 30 interested parties (if you send a mail and it bounces, ordering for the edition is closed).

- The first 18 responders are guaranteed a print; everyone else will be on a waiting list in order of the timestamp on their email. If something doesn’t work out with any of those first 18, I’ll proceed down the list until all 18 prints are spoken for.

- By 9 p.m. on the evening of Feb. 29th, I will send a PayPal invoice to your email address. You will have until 9 p.m. on Wednesday, March 2nd, to pay the invoice before your print is offered to the next person on the waiting list.

- All prints that are being shipped will be shipped by March 9th.

Apologies if this seems like we’re exchanging classified information in a virtual parking garage. Really it’s just an email and timely follow through.

I’ll never say “never” but it’s unlikely I’ll be producing more art prints from the Virtuoso project — they simply take too much time to make and sell individually. Lost Art Press has found a means to fulfill poster orders easily (in case you’re wondering, the lack of reliable fulfillment is why this art print isn’t an official LAP offering) and we’re looking into ways to make other images from the image archive available on a more mass-produced product. So if you aren’t able to procure one of these extra-special art prints, maybe we’ll have something for your wall later this year. Feel free to contact me, though, if you are interested purchasing (entire) limited editions of other photographs of mine or if you have an interesting photographic project in mind.

No, I do not do pet portraits…

— Narayan Nayar