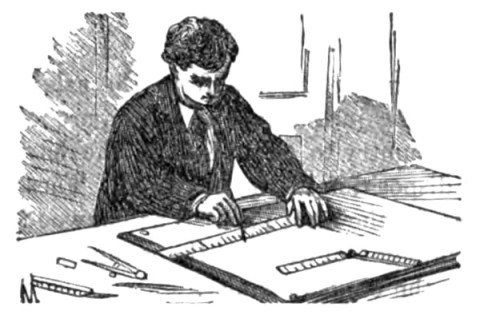

Joiner working at his bench (høvlebænk) 1767.

The above image was reprinted in a 4 volume set of Danish craft history books:

Håndværkets Kulturhistorie – Copenhagen 1982-1984.

The book titles in English are:

Vol. 1: Craft Coming to Denmark. The time before 1550.

By Grethe Jacobsen.

Vol. 2: Craft in Progress. The period from 1550 to 1700.

By Ole Degn and Inger Dübeck.

Vol. 3: The Craftsmanship and State Power. The period from 1700 to 1862.

By Vagn Dybdahl and Inger Dübeck.

Vol. 4: The Race with the Industry Period from 1862 to 1980.

By Henrik Fode, Jonas Miller and Bjarne Hastrup

The period source for this image has eluded me. All references point back to the reprint, which I don’t intend to purchase. If anybody owns this set of books, I’d like to know if the authors included background notes for this illustration.

While I was searching for the source to the above image I came across this interesting photograph of a workshop appliance located at Sønderborg Slot in Denmark. It is described as a Fugbænk, which I believe translates as [joint(ing) bench]. The description implies that the bench could also be used for plowing.

–Jeff Burks