The first words of “The Anarchist’s Tool Chest” are “disobey me,” a paradoxical expression that underlies much of my favorite absurdist Russian literature. You can take the expression at face value, or you can think about it for a minute and consider that perhaps Gregor Samsa has not really turned into a cockroach.

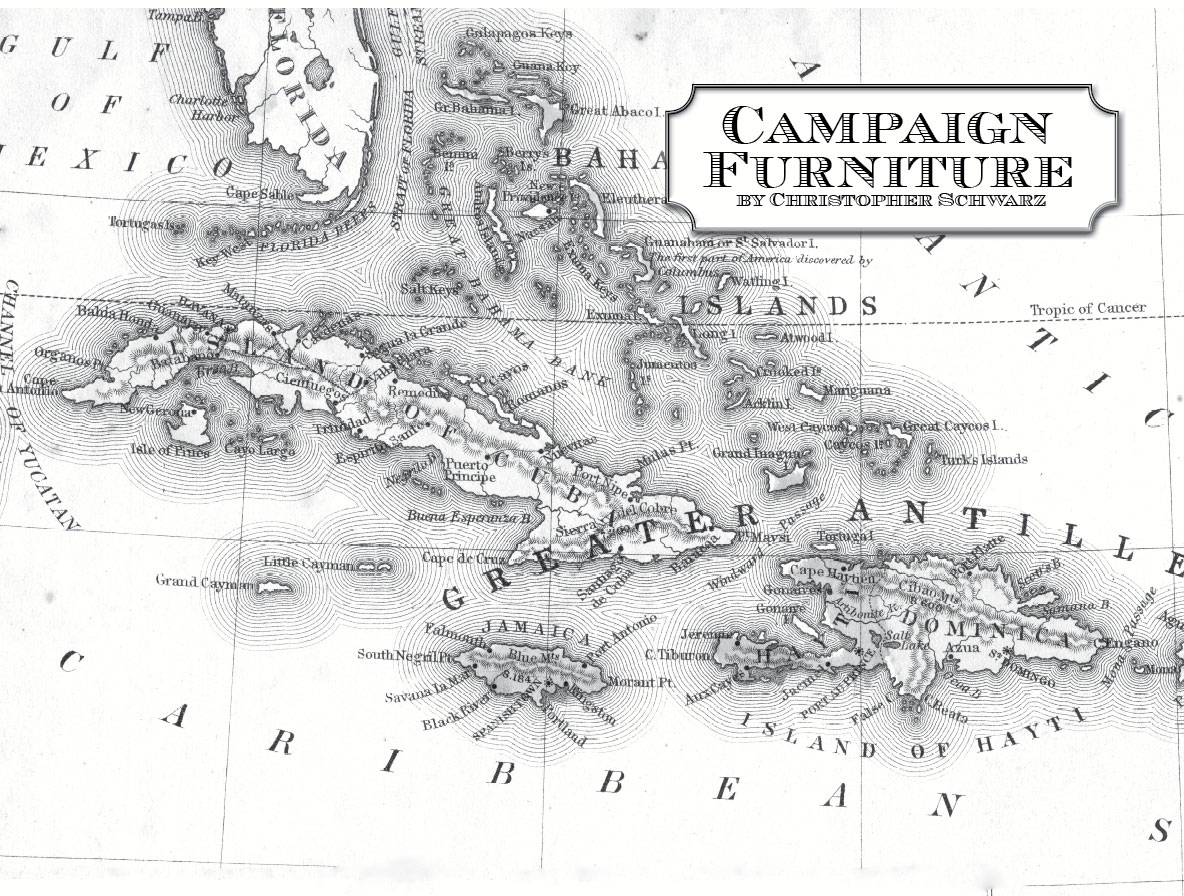

When I finished writing “Campaign Furniture,” I wanted to begin the book with Alfred Korzybski’s dictum, “The map is not the territory.” But I decided to just play it straight and not include any discussion of semantics. The book itself is a straightforward discussion of the furniture and how to build it. I don’t think this book will get me in trouble like my last one did. So I didn’t include the Korzybski quote.

That doesn’t stop me, however, from talking about my unspoken motives for the book here on the blog. While the book (the map) is about campaign furniture, the uncharted territory it describes is far different.

After 15 years at Popular Woodworking, I concluded that our craft is strapped into a stylistic straightjacket (Shaker and Arts & Crafts) that does more harm than good. Now before you get your panties in a bundle, let me be clear about a couple things: There’s nothing wrong with either of those styles. I love them both. I also love Oreos, but an exclusive diet of them is a bad idea. Also, I was part of the problem. I wrote, approved and encouraged the publication of hundreds of pieces dealing with Shaker and Arts & Crafts.

So I also want to be part of the solution. “Campaign Furniture” is part of that. “Furniture of Necessity,” my next book, is the next step in that direction.

I want readers to explore other styles, even if it isn’t campaign style or vernacular furniture. There is a world of furniture styles out there that are begging to be built. And it’s furniture that beginners can handle. Danish modern, Bauhaus, Japanese Tansu, Chinese furniture (a fricking world of Chinese furniture) are just a few of the styles out there that don’t require an 18th-century apprenticeship to build and are beautiful.

And I’m willing to take a personal hit to my income to try to open your eyes.

If I were smart, I’d write a book on birdhouses, which usually sell twice as many units as any traditional woodworking book. Or I’d do another book on workbenches, Shaker furniture or Arts & Crafts.

Writing a book on an obscure furniture style is economic stupidity. If people don’t like the style, they won’t buy the book, no matter how good it is. Books on a furniture style (even Shaker) will always sell worse than books on skills, tools or workshops. Books on an obscure furniture style usually go from the printer right to the bargain bin. (Ever seen the fascinating book on Mormon furniture? That’s exactly my point.)

Today I received my copy of “Campaign Furniture,” and it doesn’t completely disappoint me. The printing job is nice. I like the end sheets. The binding looks good – not too much glue and the stitching is solid. So I’m drinking a Stone “Old Guardian” right now to celebrate the release of what could be a monumentally unsuccessful book.

I also take a sip to hope – that some of you are willing to step outside the narrow confines of our craft and start to explore the immense uncharted territory ahead of us.

“Campaign Furniture,” for better or worse, has a map inside.

— Christopher Schwarz