Imagine it is late spring in 1898 and you are a 29-year-old Moravian-born priest traveling with a tribe of bedouins to a desolate spot to look at some wall paintings in an abandoned building. You walk in and see colorful frescoes covering the walls and ceilings. In astonishment you see a whirl of dancing girls, hunting scenes, musicians and more. After 40 minutes you have to rush out and dash off because an enemy tribe is approaching. When you return to Vienna to present your findings no one believes you. The few photos you took are lost. The painted scenes you saw don’t fit with their timelines or their ideas, you have no proof, you must be a liar.

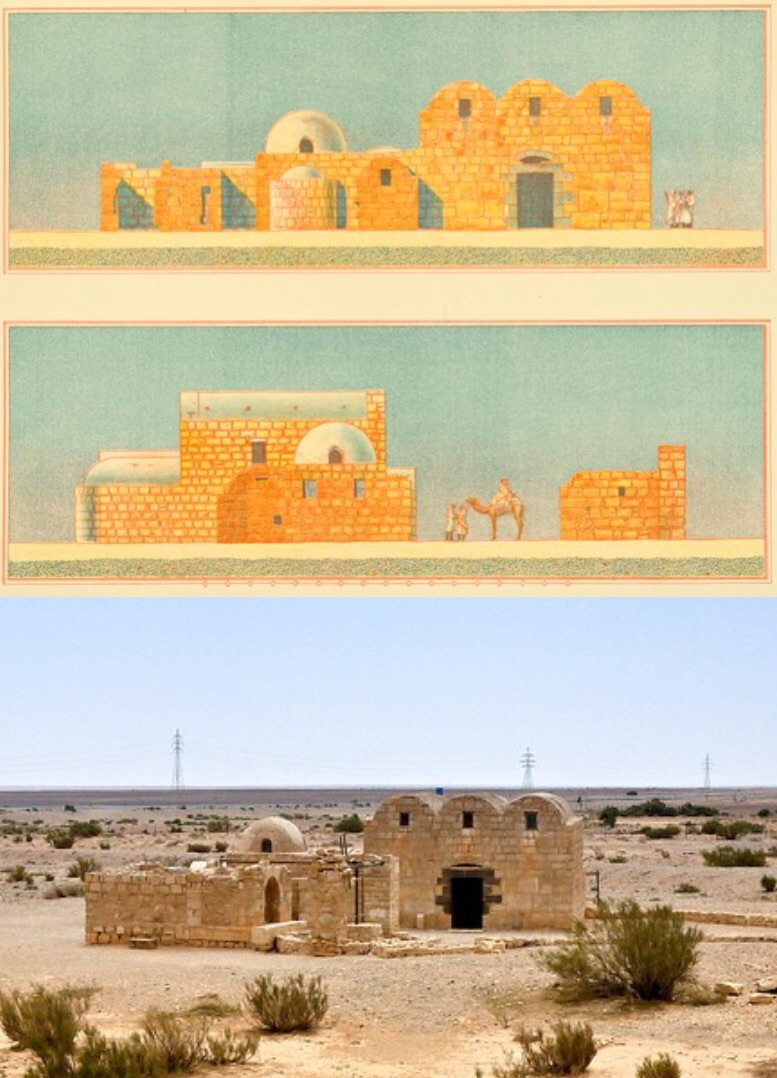

The traveler was Alois Musil, known as Musa Rweili to his bedouin friends. He returned the following year and several years after that to document the bath house, the sole remaining structure of the desert citadel known as Qusayr’Amra. Built in 723-743 and located in present-day Jordan, Qusayr’Amra was one of 18 desert citadels built during the Umayyad period. The bath house is built in the Roman style (this region was previously in the Roman Empire) with a hydraulic water supply, a triple-vaulted caldarium and unique floor-to-ceiling frescoes.

The traveler was Alois Musil, known as Musa Rweili to his bedouin friends. He returned the following year and several years after that to document the bath house, the sole remaining structure of the desert citadel known as Qusayr’Amra. Built in 723-743 and located in present-day Jordan, Qusayr’Amra was one of 18 desert citadels built during the Umayyad period. The bath house is built in the Roman style (this region was previously in the Roman Empire) with a hydraulic water supply, a triple-vaulted caldarium and unique floor-to-ceiling frescoes.

And what frescoes! To put it mildly there are girls, girls and partially clothed girls. And in between there are hunting scenes, flora, cavorting fauna and on one vaulted ceiling 32 panels of carpenters, masons and blacksmiths.

Other surviving citadels had hunting scenes, but no girls, and certainly no display of working craftsmen. But if you think about it, why not? While your guests soak in the warm waters of the caldarium surrounded by these fantastic paintings you are impressing them with your power and wealth. Including the panels of craftsmen may seem an anomaly but is another indication of material wealth and resources. The citadel and bath works were built and decorated with the skills of a small army of carpenters, masons, blacksmiths and artists. Thanks to this 8th-century showmanship, and the persistence of Alois Musil, we have more pieces to add to the woodworking record.

The panels with the sawyers and the worker on the bench are the only woodworking panels still intact enough to discern details (likely due to their locations away from water leaks). Both panels have had some restoration work. The Roman workbench detail from Pompeii (dated about 660 years earlier) is included for comparison. The craftsmen panels don’t show any innovations in tools or techniques, rather a continuation of Roman-era traditions.

The frescoes have sustained damage from almost 1,300 years of exposure to weather, water leaks, camp fires, vandalism and unfortunate efforts at conservation. Musil, accompanied by artist Alphons Leopold Mielich, attempted to treat some the wall frescoes with chemicals causing pigments to fragment and fall off. While attempting to remove sections for transport to Vienna, other portions of frescoes were destroyed. The few sections that did make it to Europe are in museums in Vienna and Berlin. Qusayr’Amra was designated a UNESCO site in 1985 and current conservation efforts are under the direction of the World Monuments Fund.

In 1909 drawings made by Mielich were published in a two-volume folio and included reconstructions of the larger frescoes. The New York Public Library has one volume of the folio and a digital copy is available on line under the title Kusejr’Amra. I was able to match a few of the 1909-era drawings with more recent photographs.

— Suzanne Ellison