It’s a bit difficult to put a label on this book. It’s not really a catalog of the pieces produced by Nakashima Woodworkers, but it is filled with drawings and images of the pieces the company makes. It’s also a short history of the workshop, a close explanation of how they work and a sometimes-lighthearted look back at George Nakashima’s life and work.

Called the “Process Book” and written by Mira Nakashima, this 2023 book is unlike any other book I have encountered in my career as a publisher and a woodworker.

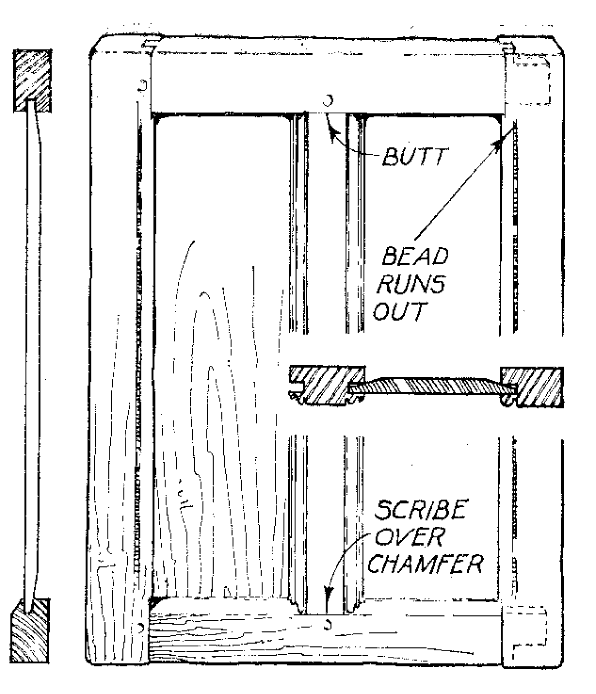

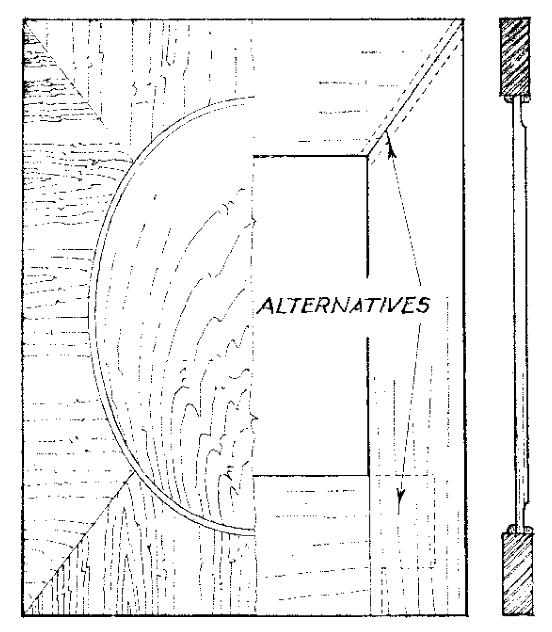

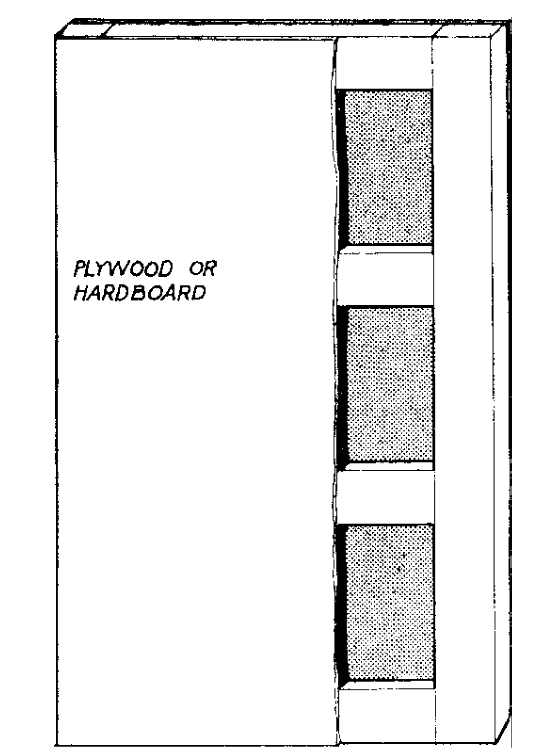

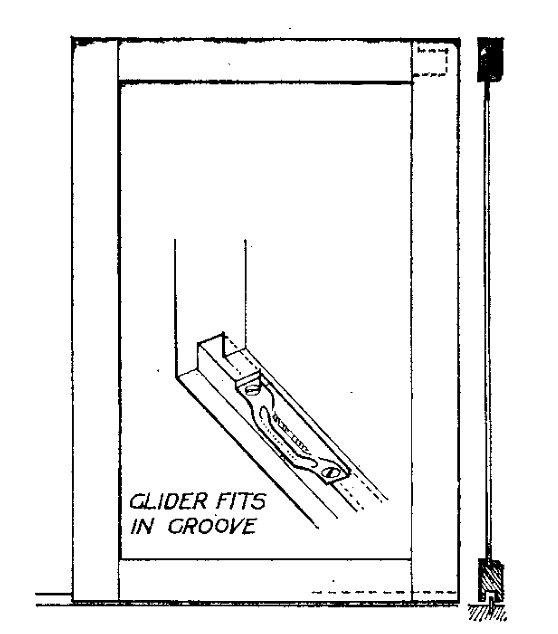

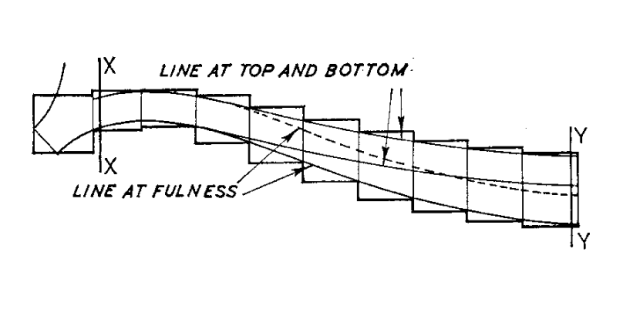

The book is a deconstruction, showing you its structure like a wedged through-tenon or visible dovetails. When you first unwrap the book, it looks like it has a dust jacket. But when you open the jacket, you find that the jacket comes off and unfolds into a large poster. One one side is a photo of George Nakashima and on the other are construction drawings.

The book block has no boards or paper cover. Instead it is like looking at a component from a pressroom. The spine of the book shows the thread running through the signatures. And the glue that reinforces the signatures. You can see clearly the registration marks from the press (usually obscured) that guide the bindery as they assemble the book block.

And while there is no formal “cover,” the pages of the book are protected by heavy printed end sheets.

Once you start exploring the interior of the book, there are more surprises, including large fold-out sections and gorgeous photography displayed on premium uncoated paper.

The whole experience is much like experiencing a piece of well-made furniture. First you see the form – it’s a book. But as you get closer and interact with the piece you come to understand it was made with incredible care and it gives up its secrets slowly but inevitably.

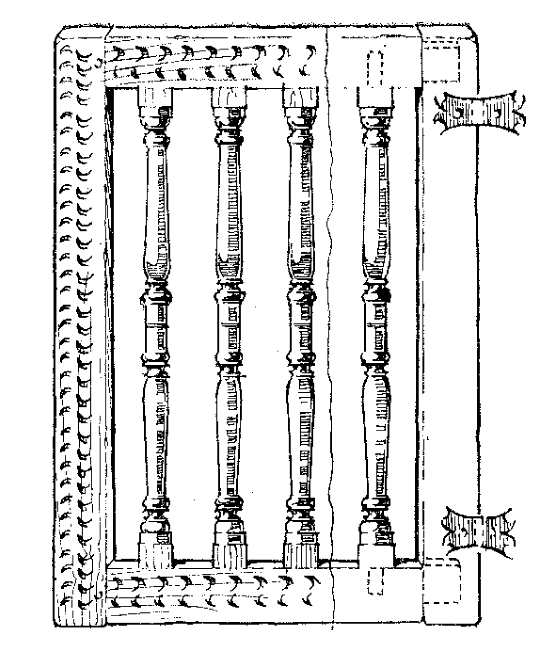

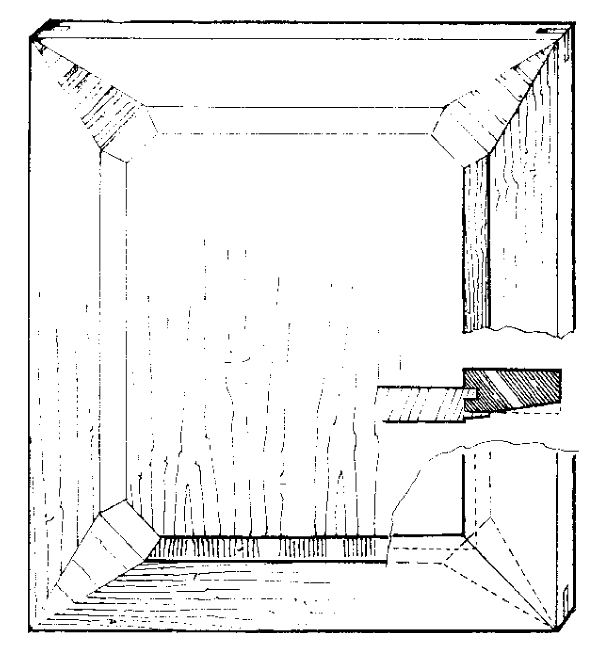

If you love the work of George Nakashima and his daughter, Mira, this book is essential reading. The book is filled with sketches of the pieces the shop sells, plus many archival images and drawings that aren’t shown in George Nakashima’s “Soul of a Tree.”

The book details the process of building a piece of furniture for both the customer and the workers. It explains with great clarity how wood is chosen for each piece of furniture in a way that helps determine the final design of the piece.

And as you work your way through the book, folding and unfolding and marveling at this detail or that curious drawing, you become an active participant in the creation of the book. After you are done with the text, you put it all back together again. And there it is, the form you started with.

The book ships with a current price list (always interesting). “Process Book” is a delightful piece of work. And at only $35, it’s a steal for printing and binding of this caliber.

— Christopher Schwarz