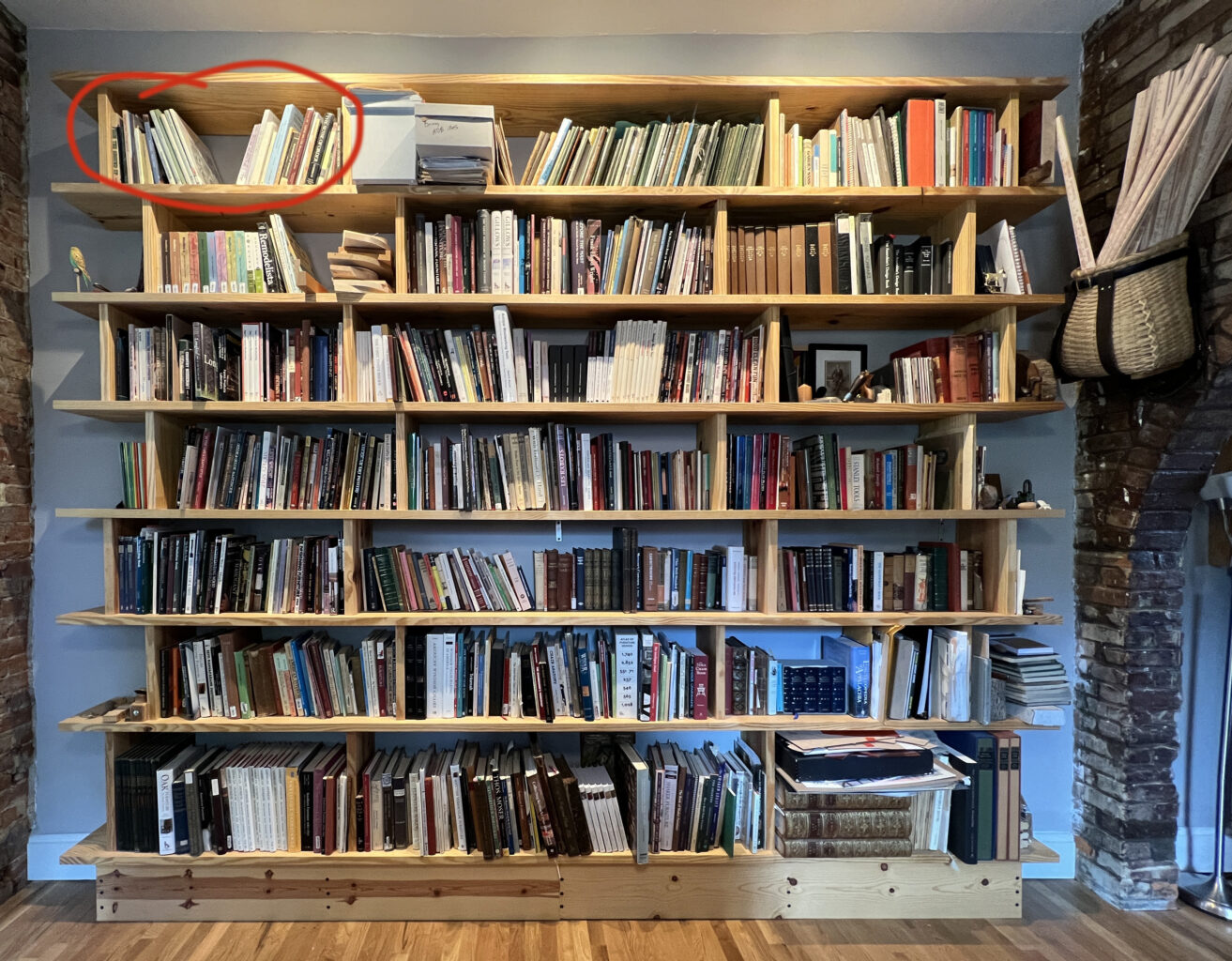

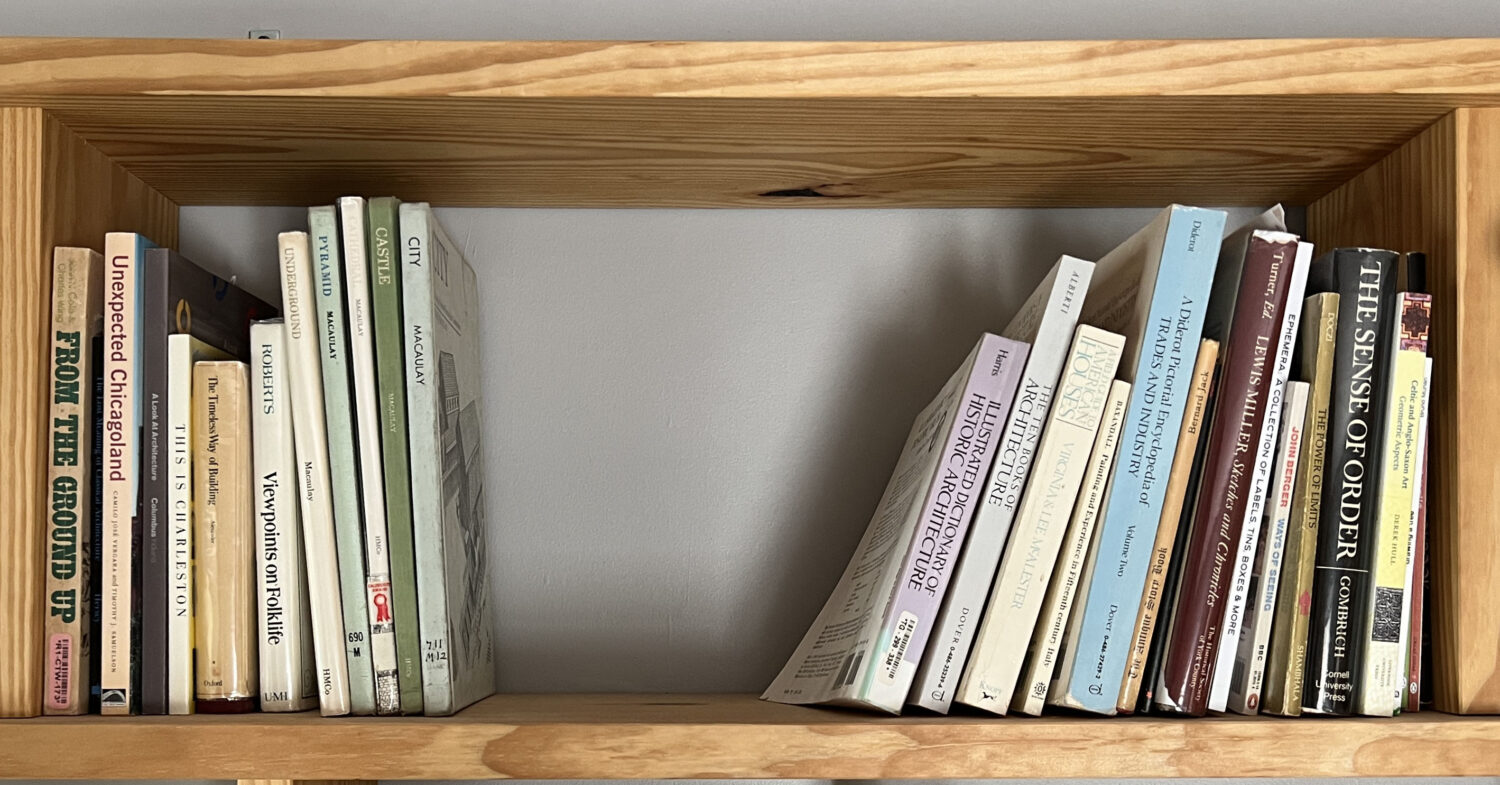

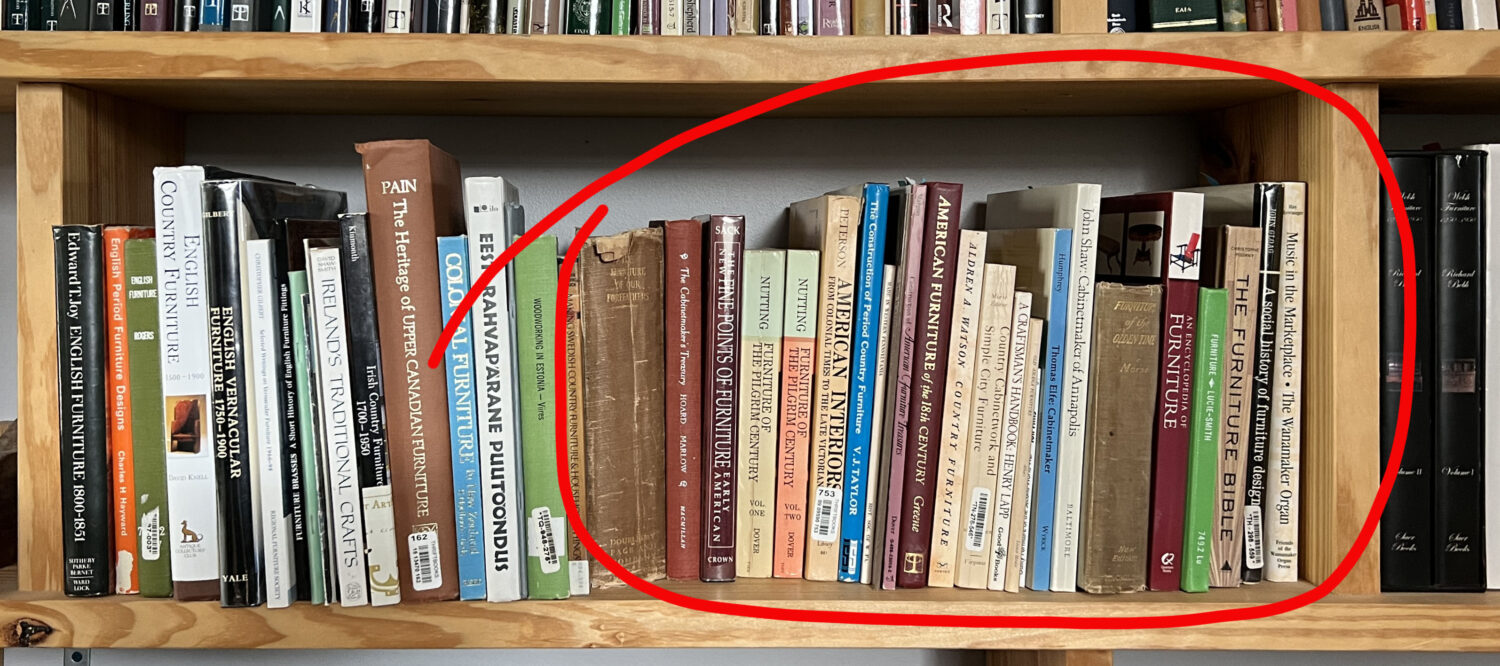

This Covington Mechanicals Library post feels like a sales pitch; sorry ’bout that. We’re up at top center of the shelves now, and that’s where we keep the stuff that’s incredibly important to Lost Art Press but – now – rarely needed. That’s all of John Brown’s columns from Good Woodworking magazine, and yearly compilations from The Woodworker magazine…the ones we didn’t cut apart to scan for our five-book Woodworker series. (The ones we did cut apart are in the white file box.)

Let’s go in publication order – both as far as the originals and the Lost Art Press books to which that shelf contributed: right to left.

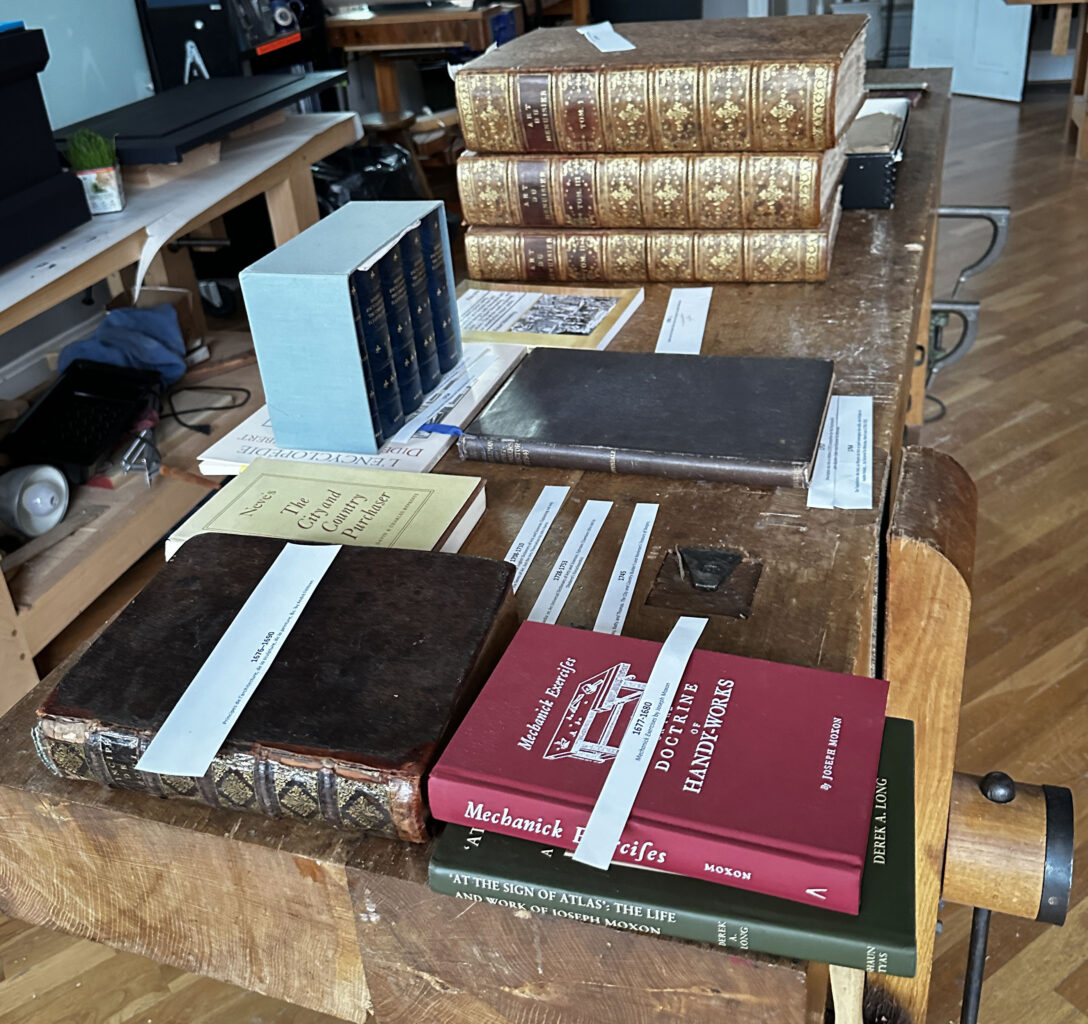

In 2007, after at least one beer too many, Christopher Schwarz and John Hoffman discussed acquiring the rights to reprint some of Charles H. Hayward’s fantastic writing from The Woodworker magazine, of which he was editor from 1936 to 1966. There had been unauthorized reprints before (shame on those people), but nothing legit.

Long story short: We got the rights to use some of Hayward’s writing in physical books only – that’s why there are no pdf versions available of any of “The Woodworker: The Charles H. Hayward Years” volumes.

I can’t remember exactly when the project began in earnest, but I do recall sitting around the trestle table in Chris’s dining room in Ft. Mitchell, Ky., circa 2010 to discuss the project, then going down to the shop in the basement of his old house to slice off the spines on all The Woodworker compilations from 1936-66 – because that made the pages a heck of a lot easier to scan. (And I remember the canvas bag full of the sliced-off spines that Chris kept around for years. They might have been tossed in the move to Willard Street. Or possibly they are in a box in the basement.)

It took six years or so for the acquisition, selection, scanning, editing, layout and printing – and hundreds of hours of work from Chris, John, me, Phil Hirz, Ty Black and Linda Watts to get from idea to the publication of Volume I (which covers tools) and Volume II (which covers techniques) in early 2016.

Volume III (on joinery) was released late in 2016, and Volume IV (on the shop and furniture) followed in early 2017.

It is to date the most labor-intensive project – by a long shot – undertaken by Chris, John and the rest of the folks at Lost Art Press. And in 2020, we added a fifth volume: “Honest Labour,” because Hayward’s editor’s notes were too good to not share. That project was completed in large part thanks to Kara Gebhart Uhl, who selected the columns we reprinted for each year, and wrote introductions for each annual division.

To learn more about Hayward – who I would hazard a guess is Chris’ most important woodworking/editing hero (mine is Chris) – check out two posts from 2016: “Get to know Charles H. Hayward, Part I“: and “Part II.”

Chris’ chairmaking hero, John Brown (aka JB), is represented on the left side of the shelves. Chris has written on this blog about his introduction to Brown, and his acquisition of all of John Brown’s columns. Well, there they are – and some of his and Chris Williams’ favorites were reprinted (with permission, of course) in Chris Williams’ book “Good Work: The Chairmaking Life of John Brown.” (Chris W. spent about a decade with Brown in Wales, and “Good Work” recounts their work together, from the day that Chris called JB until the day his mentor died in 2008.)

Tucked alongside the Good Woodworking issues and photocopies are prints of Molly Brown‘s illustrations for “Good Work” – gorgeous drawings that honor her father’s passion for chairmaking and for Wales.

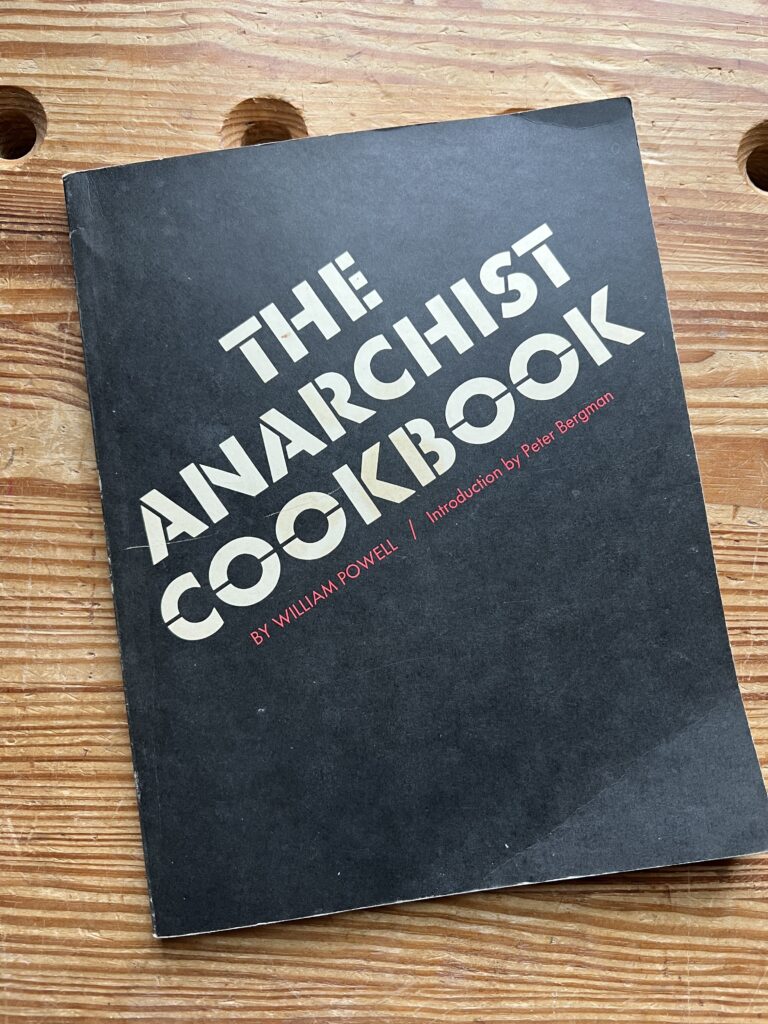

While “Good Work” wasn’t a crazy project like Hayward, getting the rights to reprint JB’s “Welsh Stick Chairs” was a personal investment for Chris Schwarz. “My affection for Brown was three-fold. First, it was about the Welsh stick chair. He introduced me to the form that has guided my taste in chairs since 1996,” wrote Chris. “Second, it was about hand tools. I’d been using hand tools almost exclusively since age 11, and it was shocking that someone else I admired did the same thing. I didn’t do it by choice (my parents wouldn’t let me use power tools), but thanks to Brown I decided that I was OK. And third was how he declared ‘I am an anarchist’ in one of his columns. (In fact, his column was labeled “The Anarchist Woodworker” for a period of time.)”

I remember a lot of metaphoric hair pulling as he negotiated rights with all of JB’s heirs – it was Matty Sears (one of JB’s sons), who finally made it happen. And I remember how happy Chris was to bring this book back into print.

– Fitz

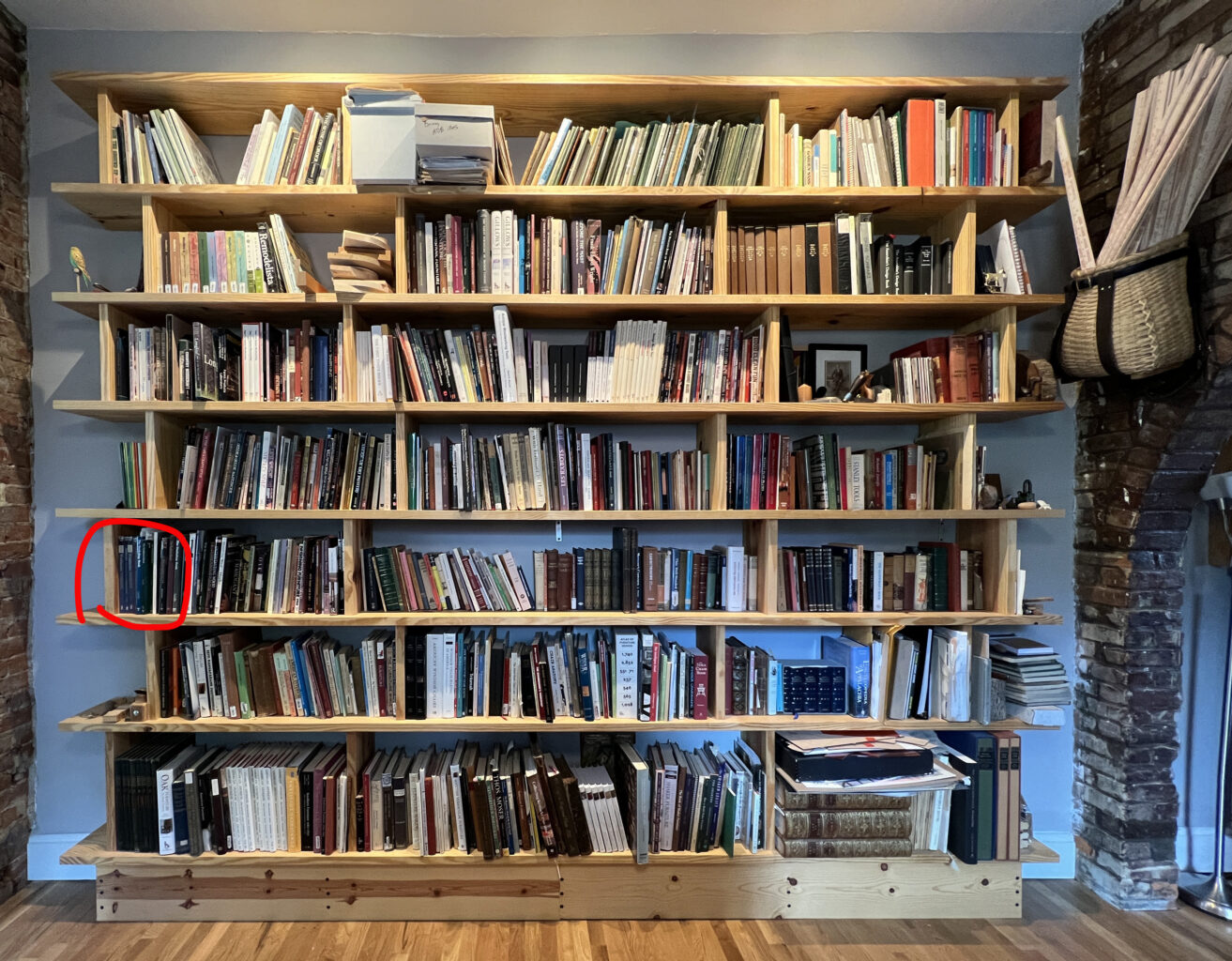

p.s. This is the 14th post in the Covington Mechanical Library tour. To see the earlier ones, click on “Categories” on the right rail, and drop down to “Mechanical Library.” Or click here. NB: I have used the same picture at the top of every post, simply circling the cubby I’m covering in a given post. For the close-ups, I’ve taken new pictures each time. The odds on that cubby still containing all the same books in the same order as the main image are slim indeed (in case you zoom in and see discrepancies).