I always felt odd building French workbenches using English (or worse) inches.

Anyone who has studied the history of measurement knows that there are as many systems of measurement out there as there are cultures and epochs. Surprisingly, many of them are similar because they are based on the human form. But they are all a little different.

Rather than whitewash these differences or convert them to metric, I try to incorporate them into my work in the same way you would never put a Roman ovolo on a Grecian piece.

At the vanguard of this curious approach is Brendan Gaffney, a woodworker and musical savant who has been taking a deep dive into alternative measurement systems. He recently made three rulers for sale based on Japanese, Roman and Egyptian systems. I purchased the Roman ruler and it is a work of great beauty. I plan to use it in constructing two upcoming Roman workbenches.

And now Brendan is exploring the 18th-century French measurement system.

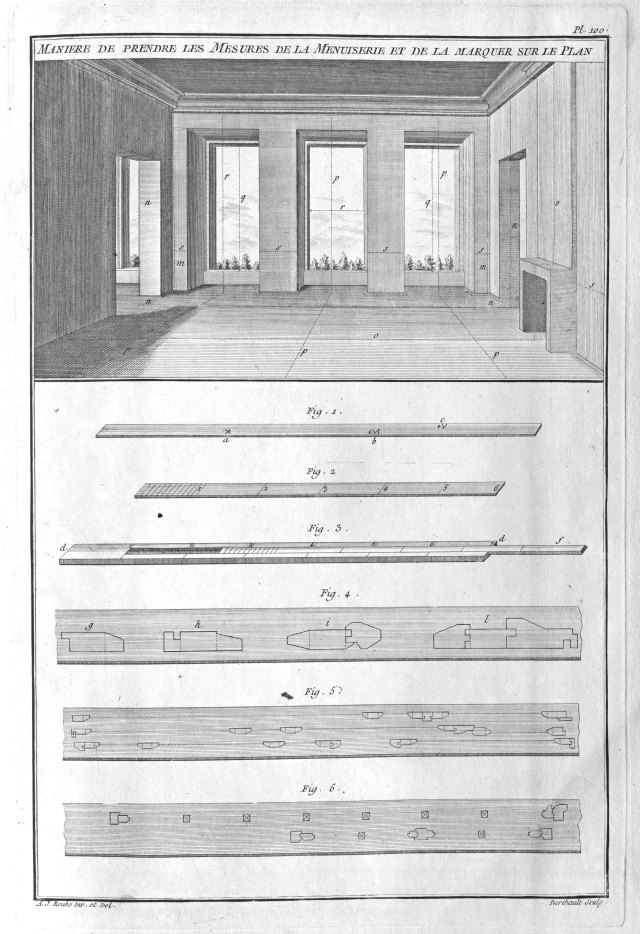

After some back and forth, Brendan has constructed French “fathoms” that are based on A.J. Roubo’s plate 100 from “l’Art du menuisier.” Here’s Roubo’s description of the fathom:

“Woodworkers use fathoms as the fundamental unit for taking their measures. This is nothing other than a ruler of 6 feet in length divided into feet and one of these divisions into thumbs so as to be able to know how far each part they are measuring is in length. There are those who do not use fathoms but simply use a ruler of whatever length on which they mark their measurements.”

Brendan’s version, which goes on sale on Saturday, is faithful to that description. His fathom is made from flame maple, planed true, hand-marked and finished in Brendan’s workshop. If they are anything like his other rulers, they will be spectacular.

Do you need a fathom? No. You can make your own if you think you need one. But if you’d like to support a fellow explorer who is diving deep into waters that have been uncharted for more than 200 years, you can do that here.

I’m ordering one for layout work and to help interpret the drawings from our forthcoming book “Roubo on Furniture,” which contains lots of scaled drawings.

— Christopher Schwarz

I went out of town for one weekend and it seems like the forum exploded while I was gone. A lot of advice is what people are after. Remember, if you have a question about our products, procedures in our books or anything related to Lost Art Press, the fastest way to get an answer is our forum. Check it out

I went out of town for one weekend and it seems like the forum exploded while I was gone. A lot of advice is what people are after. Remember, if you have a question about our products, procedures in our books or anything related to Lost Art Press, the fastest way to get an answer is our forum. Check it out