Editor’s note: As we revealed yesterday, we’re excited to announce that Lost Art Press will publish a book on the life and work of the late Welsh chairmaker, John Brown. Here, the author, Chris Williams, shares how he met John Brown in the late 1990s.

— Kara Gebhart Uhl

I never knew his name at the time, other than there was a mythical chairmaker from the western seaboard side of my native homeland of Wales. He made chairs by hand without the aid of electricity and lived in his workshop. In the early 1990s, with some research, I found out that he had written a book called “Welsh Stick Chairs.” It was being sold in a bookshop less than an hour’s drive from me.

I drove to Newport Pembrokeshire to buy a copy of the book. I later learned that the man I had held the door for on entering the bookshop was John Brown. He had just dropped off a box of books for them to sell. The owners were very enthusiastic at my interest in the book, and I was ushered into a side room where they showed me a chair that John had made them.

The book was a revelation to me. It was so informative on this little-known subject and included a photographic chapter that was truly inspiring. I was hooked on the chairs and the author. I read John’s monthly articles in Good Woodworking magazine fervently. His writing was great — nothing of the anorak in his articles. And I thought his take on life was so different than the norm.

My day job as a carpenter and joiner was a varied one, but the chairs were deep in my psyche by now, and I dabbled somewhat with them for a few years. Looking back they were poor. I hadn’t yet been fueled by the Zen-like teachings which were to come.

Several years later my partner, Claire, and I were in Australia and New Zealand on a gap year/working holiday. I enjoyed the change of scenery and meeting new people but something was missing. There is a word in the Welsh language, “Hiraeth,” which loosely translates to a longing, with a sadness, for an absent something — not homesick. By chance I picked up a copy of Fine Woodworking (the Nov./Dec. 1997 issue) in Melbourne in which there was an article on John Brown — a great article. It was at this point that I realized it was time for me to head home to make chairs, and to meet John Brown in person.

It was with some trepidation that I telephoned him. To my surprise, his number was in the phone book. The conversation was a blur — lots of nerves on my side. But it must have gone OK because a few days later I head west to John’s home. I was given clear instructions on the whereabouts of the workshop, but alas I got lost in the wilds of North Pembrokeshire. I eventually found the workshop down a long narrow lane under the shadow of Carn Ingli, which translates to “mountain of the angels.” It was a truly beautiful landscape of small fields with stone-walled boundaries and small wooded valleys meandering down to the Celtic sea — a landscape that obviously inspired John. The undersides of John’s chair seats were embellished with a simple Celtic cross for which the area is famous for.

I was greeted politely but hurriedly by John as he was in the process of gluing up a chair. I watched him work but also took in the hand tools that were everywhere, neatly placed in various racks and shelves. Photos, paintings and poems also adorned the walls of the workshop. I had truly come across a different type of life, at least one in contrast to my conservative Welsh upbringing. It felt more like a home than the cold and soulless workshops that I had spent years in. I felt at home when I was offered a cup of tea. Two pots later, it was it time to leave. I left buzzing after the experience and little did I know then what adventures the next 10 years would bring for both of us. It was far from a happy-ever-after story but one that would change my life profoundly forever.

— Chris Williams

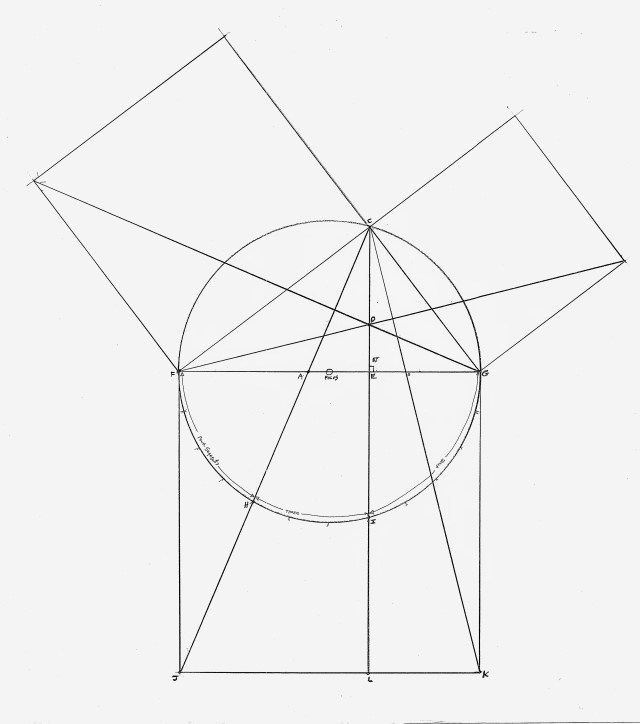

In this sketch I did of a Masonic “

In this sketch I did of a Masonic “