We’ve long wanted to offer Lost Art Press stickers to decorate your tool chests, machinery and guitar cases. But it was difficult to fulfill them without losing our shirts on warehouse fees or spending our days stuffing envelopes (when we should be making books and furniture).

My oldest daughter, Maddy, has agreed to take on the task of managing the stickers and fulfilling the orders; she’ll also make a few dollars on the side as a result. She’s an animal science major at Ohio State University, so every penny helps because we’re paying out-of-state tuition.

We’re eventually going to offer a way to order these on the web and send them to international customers. But until we can work that out without getting swallowed by fees, we’re going to do it a real old fashioned way.

Send a self-addressed stamped envelope (SASE) with a $5 bill to the following address:

Stick it to the Man

P.O. Box 3284

Columbus, OH 43210

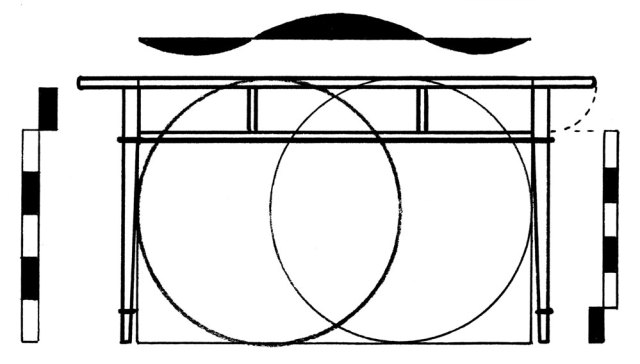

Maddy will take your SASE and put three high-quality vinyl stickers – one of each design – in your envelope and mail it to you immediately. These are the nicest die-cut stickers we could find and should even be suitable for outdoor use, according to the manufacturer. The stickers are made in the United States, of course.

We’ve made 500 of each design. When we run out, we’ll issue three new designs.

Note: We don’t have any of these stickers at our Lost Art Press warehouse. Heck, I have only one set (it cost me $5). So asking for special favors from our customer service department won’t work (or help them do their job). We hope to roll out this sticker offer to everyone on earth soon, but these things take time. So please be patient with us.

— Christopher Schwarz