Order “Dutch Tool Chests” (by me!) by 11:59 p.m. Wednesday, Dec. 11, to get a free pdf with your book order. Until then, the book and pdf is $39. At midnight on Wednesday, the pdf will cost $9.75 extra if ordered with the printed book.

“Dutch Tool Chests” gives you the in-depth instruction you need to build your own slant-lid tool chest (in two sizes) – from choosing materials, to the joinery, the hardware, the interior parts that hold your tools and the paint. Plus, plans for a mobile base that provides more storage and helps you move the chest around your shop. (Oh – and a brain dump on how to cut through-dovetails – the thing I most often teach.)

My goal in this book is to not only help you make a place to put your stuff, but to help make you a better hand-tool woodworker.

But my favorite part of the book is the gallery, which includes 43 chests from other makers, with ingenious ideas for using the chest’s tool bay (or bays). Clever rolling bases. Oversized (or undersized) chests. Imaginative uses of the back of the fall front and or/underside of the lid. And other unique storage solutions and uses that set them apart.

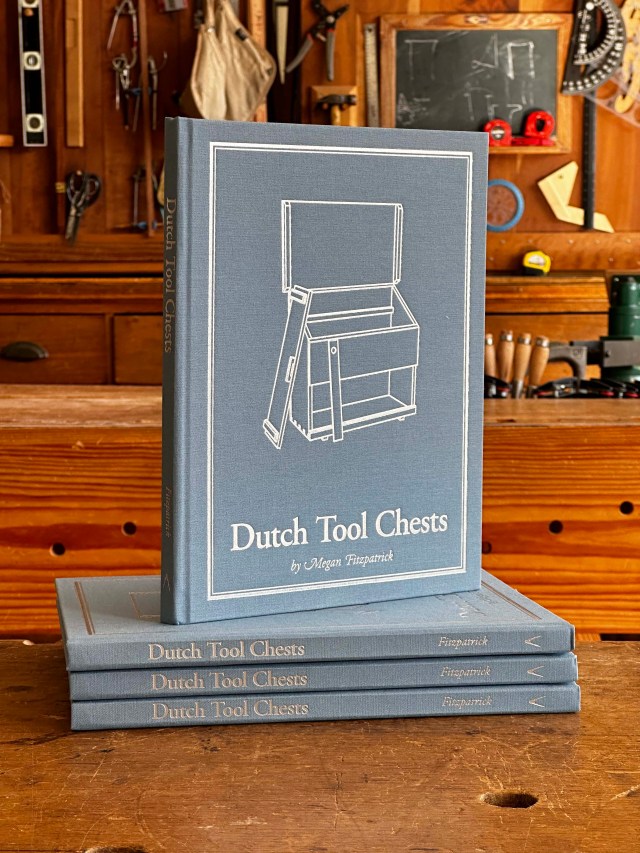

Like all Lost Art Press books, “Dutch Tool Chests” is printed in the United States. The pages are folded into signatures, sewn, glued and reinforced with fiber-based tape to create a permanent binding. The 192-page interior attached to heavy (98-pt.) cotton-covered boards (blue cloth, of course!) using a thick paper hinge. The cover and spine are adorned with a foil die stamp (which won’t help you build a tool chest – but it looks pretty nice, if I do say so myself!).

– Fitz

p.s. If you buy “Dutch Tool Chests” from Lost Art Press, you might wonder about that scribble on the half-title or title page. That illegible scrawl really is my signature – I’m signing every copy that ships from our Covington warehouse.

Like this:

Like Loading...