Kara Gebhart-Uhl, Christopher Schwarz and I have selected a few of our favorites from “Honest Labour: The Charles H. Hayward Years” – some have already been posted; there are some still to come. Chris wrote about the project that “these columns during the Hayward years are like nothing we’ve ever read in a woodworking magazine. They are filled with poetry, historical characters and observations on nature. And yet they all speak to our work at the bench, providing us a place and a reason to exist in modern society.”

Our hope is that the columns – selected by Kara from among Hayward’s 30 years of “Chips from the Chisel” editor’s notes – will not only entertain you with the storied editor’s deep insight and stellar writing, but make you think about woodworking, your own shop practices and why we are driven to make. When Australian toolmaker Chris Vesper (vespertools.com) read “A Kind of Order” it prompted him to write a few responses, one of which we give you below.

— Fitz

Everything in its Place

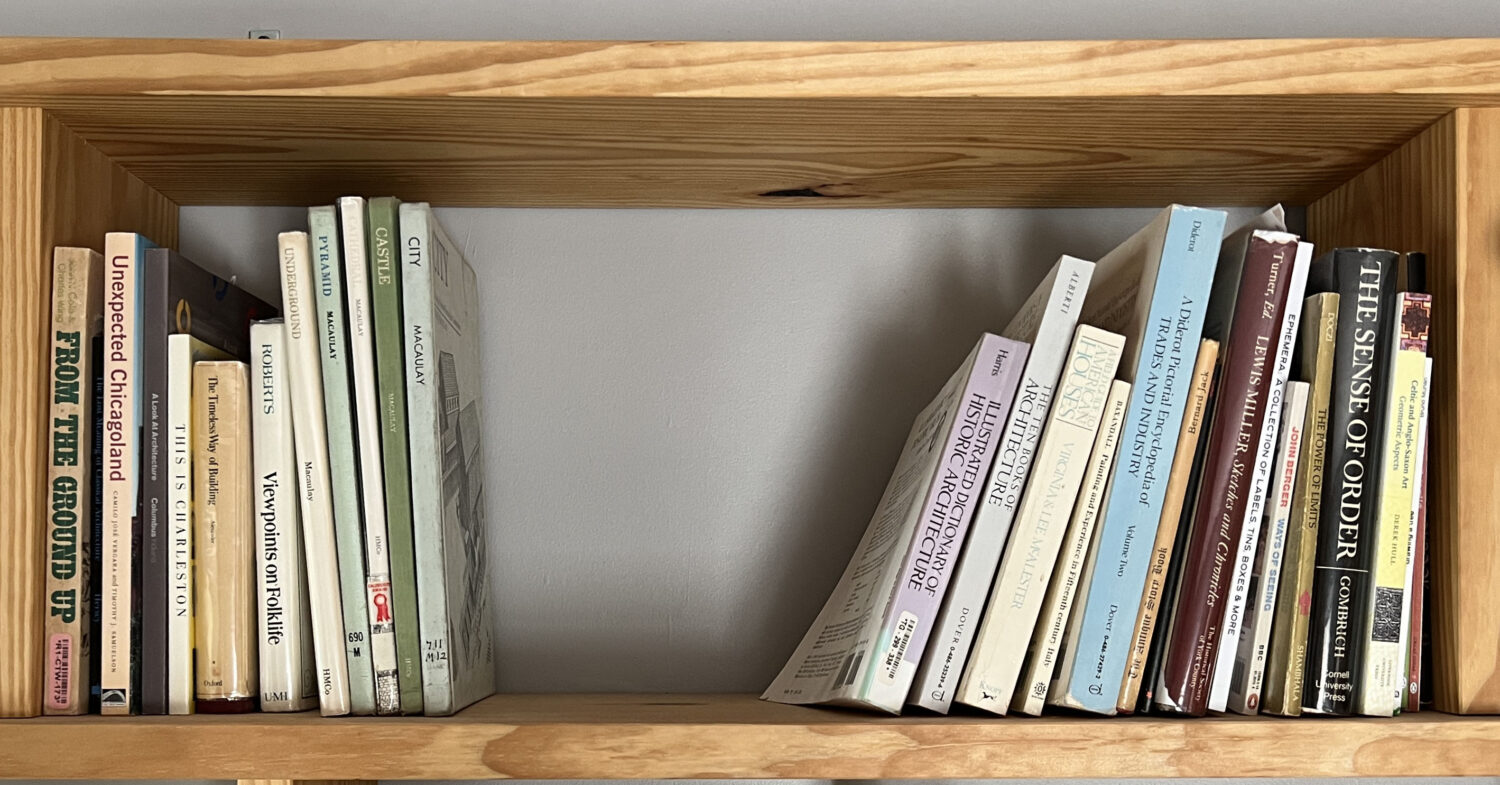

Hands and mind work as one to create when a maker is in the zone – be it woodwork, making furniture, fixing the lawnmower, working on an old car, or machining some gizmo in the sanctity of space that is your workshop on a lathe and milling machine.

When working on a project or even just tinkering the excitement can be palpable, especially when the finish is in sight among the setbacks (and occasional oopsies). The bench is a mess, with tools everywhere, things lost under piles of wood shavings and no cares given. And we all know this one: “That 10mm socket has got to be somewhere,” then many minutes later: “HOW the heck did it get there??!” Clearly too much fun is being had! Time lost equals the inverse of size be it chisels, sockets or even spanners. Big ones are easy to find – but small ones?

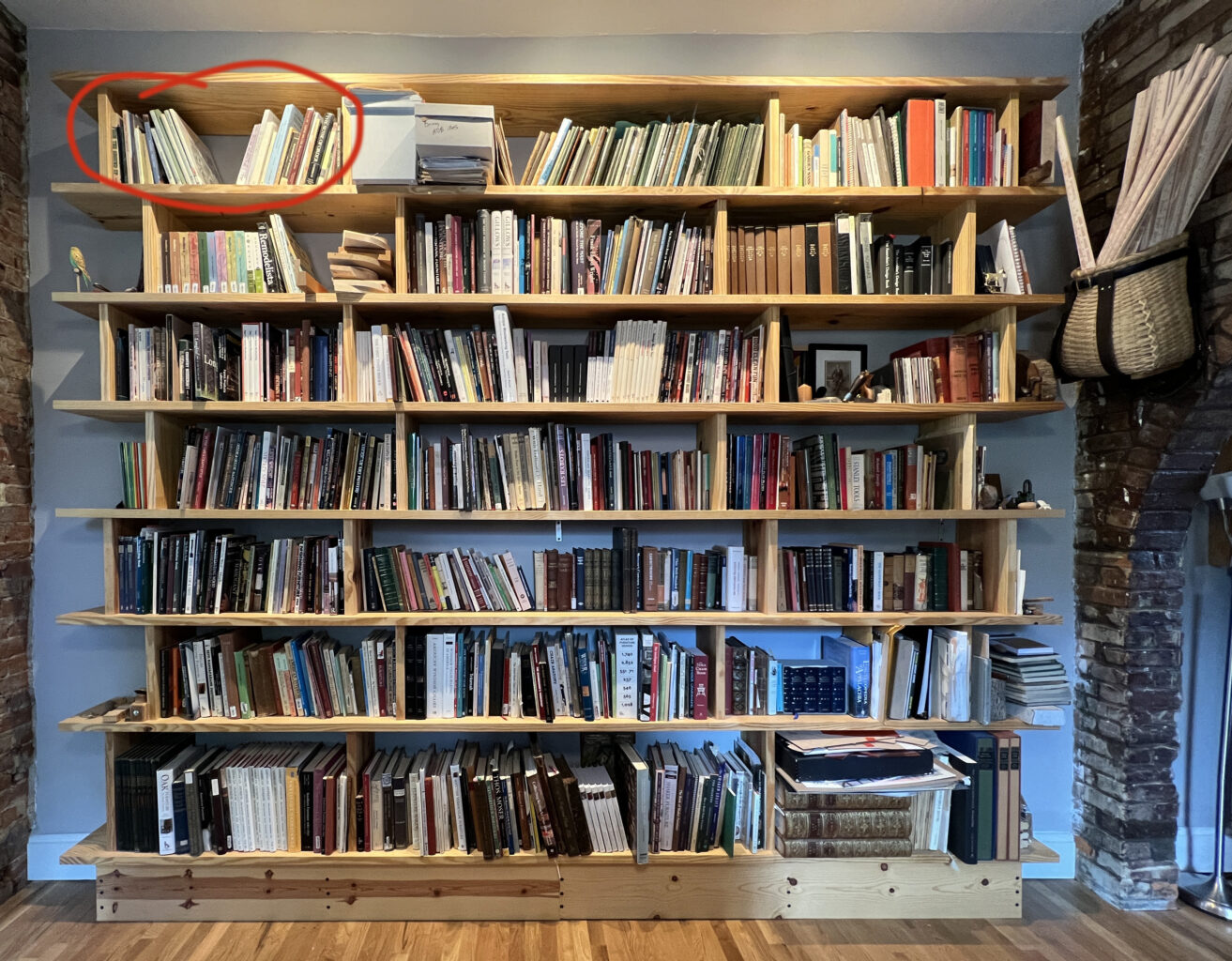

In our education as makers we refer to glossy mags or online tutorials that show impeccable workshops with perfect lighting. You may even feel some shame at your own space, so you set personal goals; you dream of what could be. But you can’t see that great pile of crud just out of their camera shots.

As for some professional work, with undersides of tabletops and backs of drawers sanded and polished to within an inch of their lives (not to mention the bits you actually see): this way of work is not for everyone, be it from lack of desire or a skill set not quite up to it. We see this perfection and perhaps gaze over our own work, and wonder at our own pleasing sanctuary of shavings piled up knee-high from attacking tear-out in a board. Perhaps we observe the results of a slightly wonky glue up. We see tools not stored properly and perhaps deteriorating from rust or being banged about – all that work to get those tools shiny the first time is lost.

In the intensity of enjoyable work, things will inevitably slip and chaos creep in. In machining work, the tool cart empties as the bench and floor fill with tools, grease and some strange black goop that gets on everything one touches. In woodworking, the tool cabinet and workbench are similarly affected (minus the black goop, hopefully). After a good, all-absorbing session of work I find it therapeutic to tidy and clean as I think back over the job, the tools used and why, the mistakes and the triumphs. Be it a daily ritual or an end-of-job ritual it’s a nice one to have.

Everything in its place.

But always keep this in mind: When I take a photo for social media you don’t know about the unsightly pile of freaky colored rags or glue encrusted ice-cream containers I just flicked out of the way to make the shot a little better.