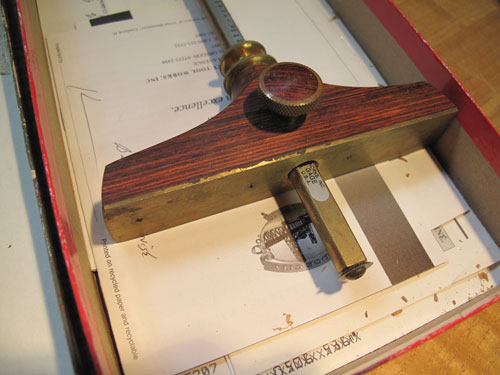

SOLD: Ultra-modern Stanley block planes stink. But this is not one of the stinkers. I bought this plane in 1996, right before the great plane apocalypse. This is a fine worker with a Hock blade (which cost almost as much as the plane itself).

I’ve tuned this low-angle tool up pretty well. The sole is flat. The iron is prepped (it does need a honing). So it’s ready for woodworking, as opposed to rough carpentry.

I hate to see this one go. But it needs to.

Price $40 plus domestic shipping. SOLD

About Tool Sales on My Blog

Please read this if you are interested in buying a tool. Why am I selling these tools? Read this entry before you freak out. There is no “master list” of tools that I can send you. I am working through several piles of tools and will list them when I can.

Want to see only the tools that haven’t sold? Easy. I’ve created a category for that on this blog. Click here and bookmark that page. When you visit that link, you’ll see only the tools that haven’t been sold.

While you can ask me all the questions you like about the tool, the first person to send me an e-mail that says: “I’ll take it,” gets the tool. Simple. To buy a tool, please send me an e-mail at christopher.schwarz@fuse.net.

Payment: I can accept PayPal or a personal check. As soon as the funds arrive, I’ll ship the tool using USPS. If you want insurance, let me know. I’m afraid I can only ship tools in the United States. Shipping internationally is very time-consuming and paperwork-heavy. My apologies in advance on this point.

If you don’t like the tool when you get it, I’ll be happy to refund your money if you return the tool. But postage is on you.

— Christopher Schwarz