During the last eight years I’ve tried to refine how I explain how to use a handplane to students. The biggest problem the students have isn’t ignorance. I wish that were the case. Instead, their biggest problem is they have been flooded with so much contradictory information that they are paralyzed.

So I’ve been trying to increase the signal and decrease the noise so they can focus on what is important. To help cement these ideas, I’ve created a list of principles relating to handplanes. Here are the ones for the tool’s cutting edge. The most important one is No. 10.

1. A sharp edge is two surfaces that intersect at the smallest point possible. This is called a “zero-radius intersection.”

2. A dull edge is where damage has occurred (hitting a nail) or the zero-radius intersection has worn away to create a third surface at the intersection.

3. A zero-radius intersection will not reflect light. The third surface created from wear will reflect light. So you can see a dull edge as a bright line. You cannot see a zero-radius intersection.

4. In general, a tool can be made sharp (a zero-radius intersection) by ANY medium – from a grinder to a waterstone. Polishing the edge only makes it more durable. The more polish, the longer the edge will go between sharpenings.

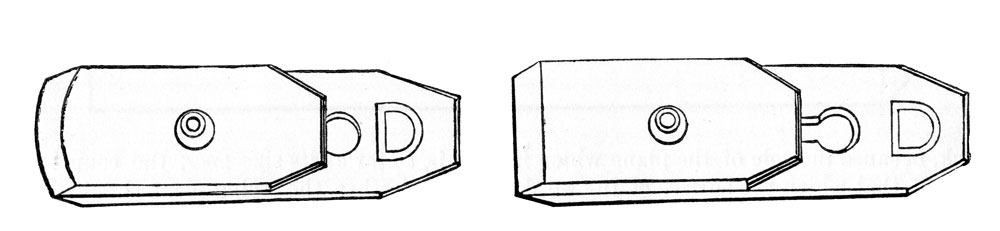

5. A sharp edge is TWO surfaces. Both must be polished for the edge to be durable. But only a small portion of the edge cuts wood (about .010” on each surface). So do not waste your time polishing steel that does not cut wood.

6. There are only three grits in sharpening: grinding, honing and polishing. Grinding removes damage or an edge that has been oversharpened. Honing removes a dull edge and restores the zero-radius intersection. Polishing makes the edge more durable. All other claims are marketing.

7. The larger the angle between your two surfaces, the more durable the edge. However, large angles can make tools unusable. If you sharpen an edge above 35°, you have to educate yourself about cutting geometry and clearance angles to stay out of trouble. If you sharpen at 35° or lower, you’ll stay out of trouble.

8. The smaller the angle between the two surfaces, the less durable the edge will be. Edges that are sharpened at 20° or lower do not work well in planes.

9. Plane edges can have a curve or be straight. Both perspectives work.

10. There is no such thing as “cheating” when it comes to sharpening. Use jigs and fixtures – or don’t. There is only sharp and dull.

— Christopher Schwarz