I just posted some details about Roorkhee Chair No. 1 here. Four or five more to follow.

Campaign Furniture: Just Put a Strap on it

Not all pieces of Campaign-style furniture require hours of insetting 30 pieces of flush hardware. In fact, with some pieces you can install all the hardware in about 10 minutes.

I call this stuff “strap-on” furniture. The brasses are applied to the surface of the piece. No wacky mortise in three axes. Just nail in four pins and you are done.

I’ve seen a number of old pieces that feature this proud hardware, though I have no idea if the brasses were original to the piece. It doesn’t take a lot of imagination to think that some antique dealers could have applied the straps and corners to dress up the piece.

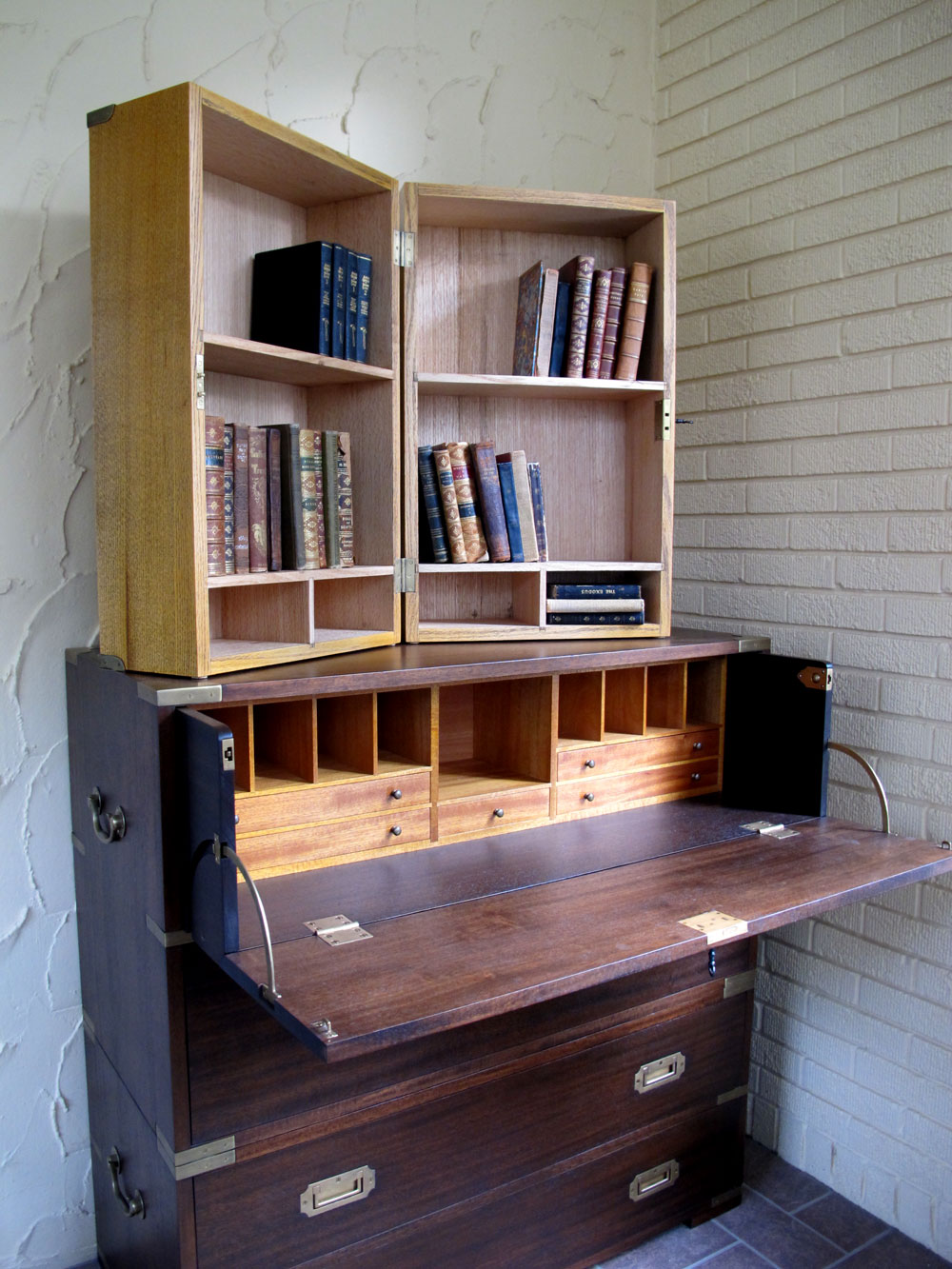

I recently finished this traveling bookcase, which carries Lost Art Press books to shows, and I decided to give it the strap-on treatment. I purchased eight smallish corner guards from Ansaldi & Sons (corner ornament, item #5293, price $2.50 each) and applied them on Monday using a hammer.

Confession: After spending a week inlaying more than 30 pieces of shaped hardware into a recent campaign chest, nailing some straps onto this bookcase was fun. And the results aren’t bad.

— Christopher Schwarz

Smythe disclaimer: I paid full retail for the $20 worth of hardware on the corners.

Finish details: The finish on the piece is one coat of garnet shellac, then a glaze of brown Minwax stain to fill the pores and then two more coats of shellac.

Name that Hide Glue – Win Something

It has been far too long since we held a puerile contest here on the Lost Art Press blog. And while driving home from our extended-family Mother’s Day celebration, my thoughts turned to (of course) hide glue.

I love hide glue in all its forms. I love it hot. I love it cold. I love it fresh. I hate it old.

The one thing I don’t like about hide glue is that I want more choices. There are only two brands of liquid hide glue out there: Titebond and Old Brown Glue. Both are fine glues with excellent qualities. But I think woodworkers deserve a third hide glue.

The contest: Name that hide glue.

While driving home I came up with what I thought was the most brilliant name ever for a glue made from a boiled animal. Are you sitting down? Good.

Deathgrip Hide Glue.

Aaaaaand, thank you. In the throes of personal glee I sent that idea to a few friends via SMS (aka, a text). One of them shot back with a name for hide glue that clearly eclipsed mine. I cannot, however, share it with you because it is so offensive that I just don’t have the stomach to endure the pile of hate mail that would follow.

He came up with a second one that I can print: Sticky McDeadhorse.

While not as funny, it is funny.

So here’s the contest: Give us the name of the next best hide glue by midnight May 16, 2012. The one that makes me laugh out loud the most wins one item from the Lost Art Press store. It can be anything that we currently have in stock.

All you have to do is post the proposed name of the glue and your e-mail. If you don’t send me your e-mail, I cannot contact you if you are the winner.

Bring it.

— Christopher Schwarz

Before the Bovines come the Aerosol Bugs

While the raw leather adds a nice Conan-like smell to my shop, I’ve got to finish the legs, stretchers and backrests for the Roorkhee chairs.

My finish of choice: garnet shellac – Tiger Flakes from Tools for Working Wood, to be specific. I love the stuff. It mixes like a martini, is easy to spray and gives me just the right color for vintage stuff.

Of course, spraying shellac always attracts the attention of the new neighbors behind us.

“It’s OK,” I’ll yell. “You can eat this stuff. They put it on strawberries and apples and pills and…”

The neighbors go inside and start closing their windows.

I guess that’s what you get for building a new house in the drainage swamp behind our house.

When I spray lots of pieces like this, I string up a clothesline between a tree and basketball goal; then I hang the parts on some wire hangers. This is how I learned to spray doors while working at the ThermaTru door company. Of course, I don’t have an oven to bake on the finish like I did at ThermaTru (that’s OK, shellac dries fast.)

And there was one more big advantage to spraying at ThermaTru – birds wouldn’t crap upon your work. The inside of my campaign chest still has some poo shadows.

— Christopher Schwarz

I Bought 3 Cows (I’m Not Becoming a Farmer)

Yesterday I went to our local Tandy Leather store and got a crash course in leatherwork from one of the guys at the store who makes gear and armor for re-enactors. Yup, I’ve decided to make the leather seats for the Roorkhee chairs from scratch.

Well, almost scratch, I didn’t raise the cows or murder them.

There is a surprising amount of overlap between the crafts of leather and wood. Sharp tools. Shaping curves using moisture. Dyes. Finishes. Metal hardware. After all, in both crafts we’re dealing with a fibrous, natural material. One just happens to have roots. The other one moos.

I’ve done some basic leatherwork before – covering an ottoman with pigskin, recovering spring seats for side chairs etc. But nothing this involved. But it looks like fun and these sling seats are a good beginner project.

I bought three unfinished skins, which should be more than enough for two chairs. I wanted to have enough to make a few mistakes. And I want to make some Anarchist underwear – whipstitching and rivets all around.

— Christopher Schwarz