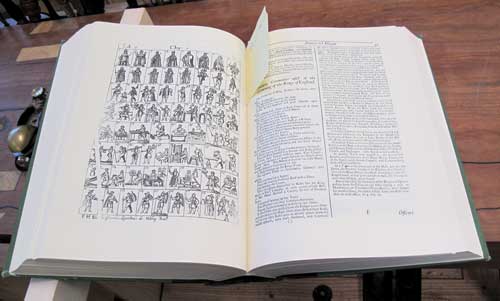

The last few days I’ve thrown up (probably a poor choice of words) on this blog a lot of excess tools that I’m selling. To balance the Karmic scales, as they are, I’m trying to give something back. And that something is excerpts from Randle Holme III’s “The Academy of Armory, or, A Storehouse of Armory and Blazon.”

This enormous 17th-century three-book work is partly an explanation of healdic symbols, but it also is an encyclopedia of the 17th-century world.

Peter Follansbee introduced me to Holme a few years ago on his blog and I’ve read snippets of it on some academic web sites that Managing Editor Megan Fitzpatrick has access to through the University of Cincinnati.

But this week, Megan did a bad thing. She checked out the entire 1972 reprint of Holme’s work by The Scolar Press Limited from the library for me, and I have been chugging through it in between 4th-grade volleyball games, editing magazine copy and waiting for glue to dry.

Here’s an odd fact about me: I always learn new material better if I type it in, and I really would like to have the full text of Holme’s sections on woodworking at my fingertips because I already see some interesting things in there that relate to Joseph Moxon and Richard Neve’s works.

So in my spare time, I’m typing in the parts of the text that interest me. And I decided to post them on the blog because it’s frustrating how difficult this information can be to come by (I cannot find this on GoogleBooks, and the 1972 reprint is difficult to find).

Why am I not providing comment or context? Because I’m still digesting things. You are getting this at the same speed that I am. But the bottom line is that it will be here for you to come back to when we’re all ready to discuss it.

All of the Holme entries are tagged “The Academy of Armory” at the bottom. So you can get to it at any time using the categories on the left side of your screen.

Sorry if it has been off-putting.

— Christopher Schwarz