When Chris Williams was visiting from Wales, he extolled the virtues of “drawing salve” – an ointment that pulls splinters out of one’s hand or what have you. And I’ve heard the same praise from other friends from across the Atlantic – the stuff is certainly more popular there than here. So what is this stuff, and does it actually work?

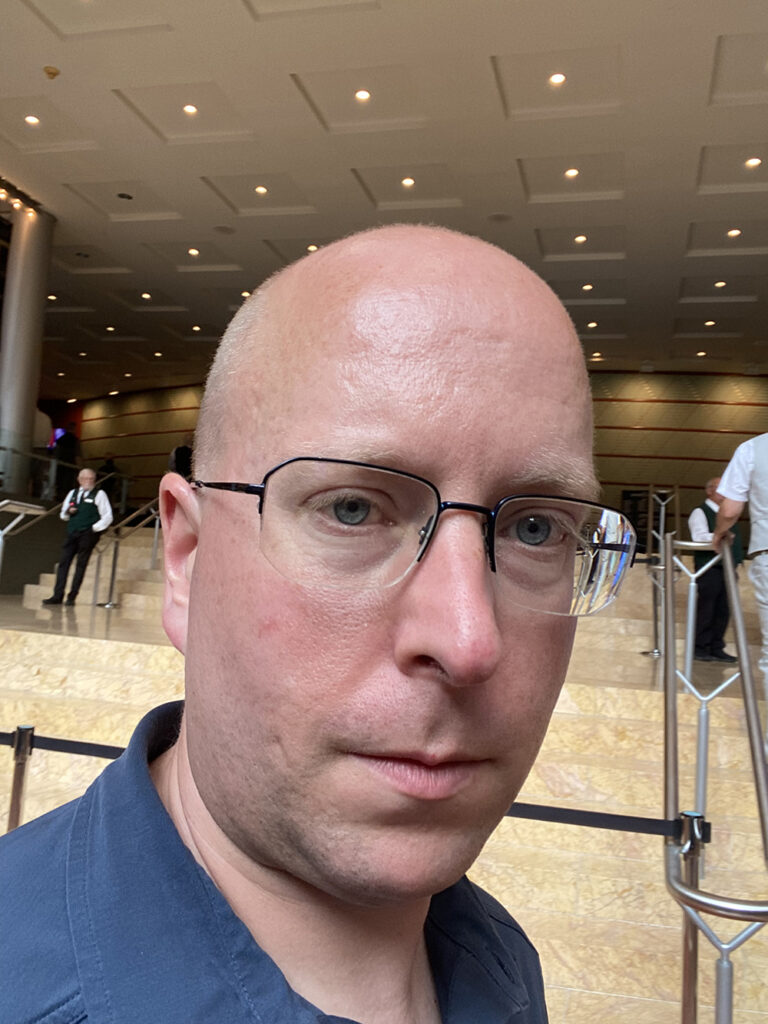

Christopher Schwarz bought some, got himself a splinter (possibly on purpose?) to find out. He reports that it did indeed help to express the bit of wood that was lodged too far beneath his skin to remove it with tweezers. What I don‘t know is how long it took for that to happen – and might it have happened in the same time span without the salve application?

We also don’t know is if there is any scientific proof that this stuff works, so we asked our friendly medical expert, Dr. Jeffrey Hill, to weigh in. He’s the author of “Workshop Wound Care,” an emergency room physician and an avid woodworker (and gardener). I’m sure he’s had plenty of his own splinters (almost certainly not on purpose), and removed more splinters from others than most of the people reading this. Below are his thoughts on drawing salve.

The term “drawing salve” somehow conjures impressions of both comfort and trepidation. Is it a soothing medicinal ointment that has been healing boo-boos since the times of Galen and Hippocrates, and is still around due to centuries of successfully treated patients? Or is it snake oil, still around because someone can make a buck or two off it? As with most things in life, the answer is probably: it depends.

A good first question might be: why is an article on medicinal ointments showing up in a woodworking blog? Well, working with sharp objects, we all tend to get nicks, scratches, and – often most maddeningly – splinters that seem to only get more painful as time goes on. In my book, “Workshop Wound Care,” I cover approaches to removing splinters. The basic approach is to first determine the direction in which the splinter fragment is oriented, take some sharp, pointed tweezers, grasp firmly, and pull with axial traction (pull in the direction the splinter is oriented).

If this is successful, and the splinter is wholly removed, you’re likely in great shape. Just wash the wound, maybe cover it with a bandage, and move on with your day. If, however, some tiny bit of the splinter remains (maybe it was too small to grasp initially or it broke off under the skin surface), you might be in for a painful couple of days as your body reacts to the foreign invader that breached the protective shield of your skin. In response to the splinter, your body sends inflammatory cells to the site to try to wall it off and kill any bacteria or fungi that might have hitched a ride on the piece of oak.

If all goes well, the inflammatory cells stream in and destroy any bacteria and fungi. The splinter is, however, far too big for a macrophage’s mouth, so the body and this inflammatory process will slowly push the splinter out past the skin. If things don’t go well, the bacteria win the day, besting the inflammatory response, and forming an abscess (perhaps more commonly known as a boil) around the splinter that will eventually need to be incised and drained. Whether things go well or poorly, the inflammatory process a splinter causes is a painful one.

Enter the drawing salve.

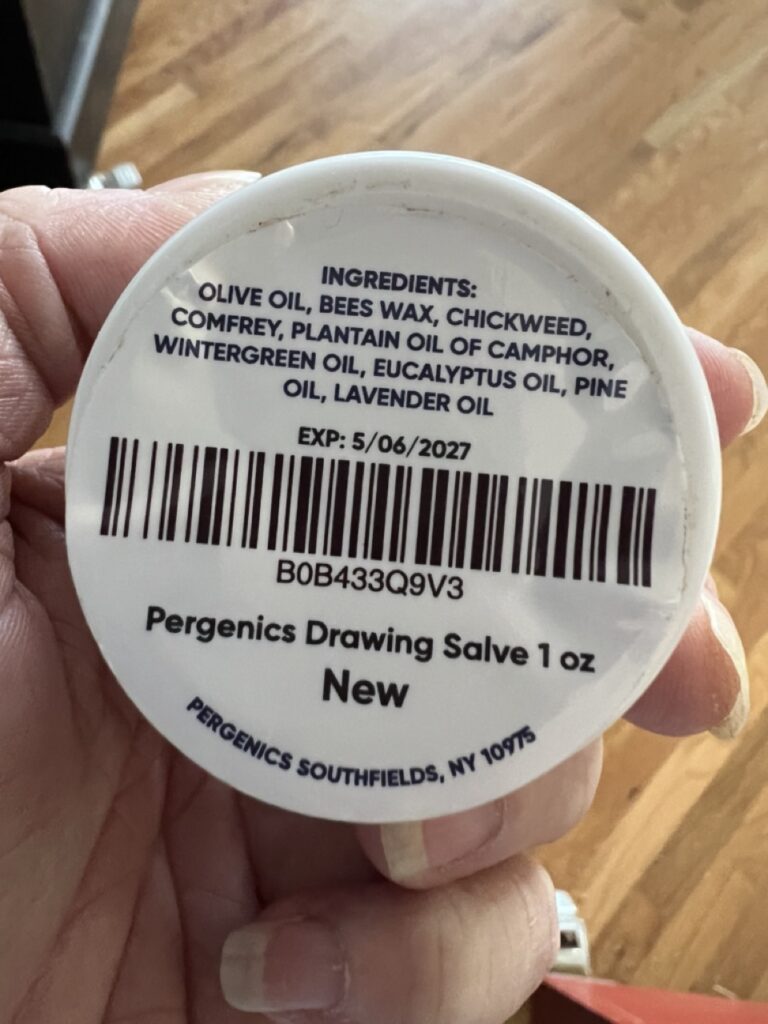

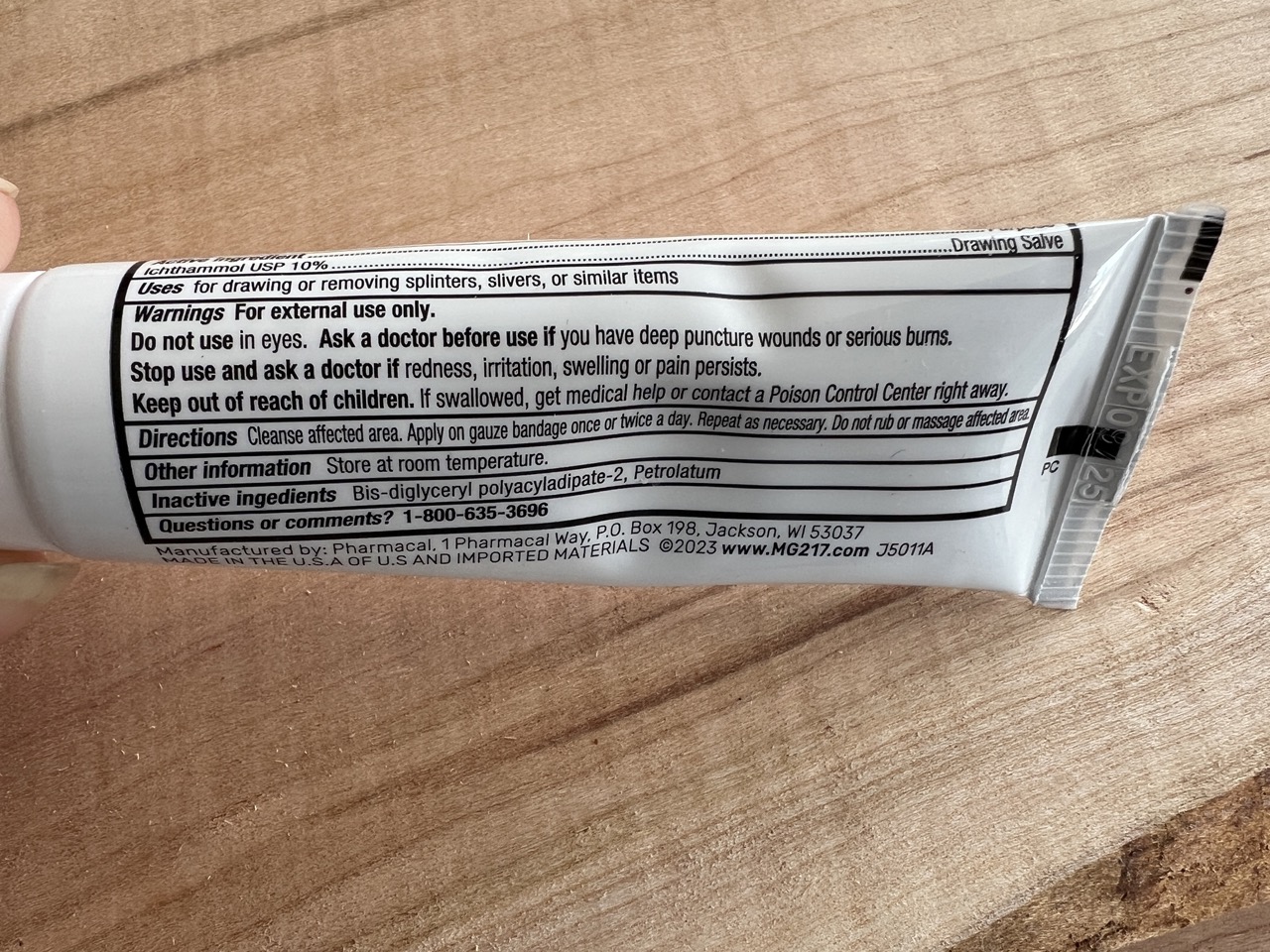

Drawing salves (and salves in general) are not one monolithic thing. They are, at their base, an ointment (a thick viscous liquid) often supplemented with chemicals with varying degrees of real or purported medical benefits. One should use appropriate caution and reason in interpreting the stated medical benefits of these preparations. Because these salves often get classified as cosmetic products, they may not undergo the rigorous testing or standards required of medications (in the eyes of the Food and Drug Administration). The FDA, in fact, specifically cautions against salves with potentially corrosive ingredients (graphic images warning at that link) or salves that claim to be able to treat or cure skin cancer, moles, warts or boils. Even salve preparations containing known medical benefits (such as the ichthammol discussed below) should be used with caution and careful attention to how your body is responding. Should your symptoms of pain and redness worsen, or should you develop fever, pus draining from the wound or streaking redness from the wound, you should, of course, seek the care of a medical professional.

Ichthammol, or ammonium bituminosulfate, a common ingredient in drawing salve preparations, is derived from sulfur-rich shale oil and has theorized antibacterial, antifungal and anti-inflammatory properties. It has a weak recommendation by expert consensus for the treatment of the terrible skin condition Hidradenitis Suppurativa (subtext here is that this means there’s no good evidence of its benefit, but smart people suggest it, so we sometimes do it). There’s no direct evidence that it would help get a splinter out of your body more quickly. However, its inclusion in a drawing salve makes sense from a pathophysiological standpoint. It has a sticky, thick consistency ideal for inclusion in an ointment where the goal is to hydrate and soften the skin. Its likely antibacterial, antifungal and anti-inflammatory effects might lessen the pain associated with the process of expelling the splinter from the body and may lend a hand in the eternal battle of the human immune system vs. bacteria. If the skin is soft and hydrated, it should be easier for the body to push out the tiny splinter fragment. And, if the inflammatory response (which is often overly robust) is held slightly in check, it should lessen the pain associated with having a sliver of oak under your skin.

So what’s the verdict on drawing salves? Are they snake oil or helpful, healing ointments? Should you slap them on every splinter you have and save yourself the pain that comes with pulling one out with a sharp pair of tweezers? They may have a benefit for those splinters too small to pull out, or those splinters that fracture and stay under the surface of the skin as you try to pull them free. In general, the best course of action is to get the splinter out as soon as possible, but if you can’t, a drawing salve (like ones that contain ichthammol) might help the body rid you of the splinter (and probably will make the process less painful).