I call this type of workbench builder the “Frank Sinatra” because they always do it “My Way.” In other words, a Frank Sinatra workbench is entirely disconnected from tradition and – at times – human reason.

Is this bad? Shouldn’t workbenches be a “I’m OK and You’re OK” kinda thing? If it works for you it’s right, right?

While I don’t seek to poo on anyone’s parade, there are certain guidelines for building things that are related to the human form and the work. If someone came to you and said: I’ve just rethought the idea of the chair – I’ve made the seat 24” deep so there’s more room to relax! Isn’t that great? More, more, more!

Me: Doesn’t that cut off the circulation of blood to the legs?

Designer: Hey, it works for me.

The following descriptions of my encounters with the Frank Sinatras are not an effort to quash innovation in workbench design. Instead, this is a look at what happens if you build a bench without knowing how benches are used.

How it Begins

To be honest, I don’t think I’ve ever met a Frank Sinatra in person. Instead, they are the people who read my blog entries and then send me photos of their workbenches with a note that says something like:

“Saw your Rubio bench. Thought I’d show you what a REAL bench looks like. I designed this one myself – an ORIGINAL design. Want to do a story on my bench? It’s awesome.”

The first Frank Sinatra I encountered had made a U-shaped bench that was 12’ wide and 16’ long (yes, 12 feet x 16 feet). It was comprised entirely of kitchen cabinets that were bolted together and then covered in 4×8 sheets of plywood. Imagine a giant “U” covered in plywood. And there were vises every 3’ or so.

Me: Do you run a school? Is this for your employees? Or are you Catholic like my wife and have a lot of kids?

Frank Sinatra: Nope. It’s just me. But it’s the best damn bench I’ve ever seen. Better than your Robo bench for sure.

Your Bench is for Pansies

Like many bench builders of the last 2,000 years, I like a bench to have some mass. You can work with a lightweight bench – we’ve all had to do it – but mass makes things easier.

Some people, however, take mass to a ridiculous level. One day I received an email from Frank Sinatra with photos of a bench “that makes your benches look like church picnic tables.”

I opened the attached photos. It was a French-style bench that was made entirely out of 2x12s. The top was all 2x12s that were face-glued (the top was 11” thick). The legs? 2x12s that finished out at 11” x 11”. (Elephants would be jealous.) The stretchers? 2x12s.

In all honesty, it looked like a cartoon sketch of a bench. But I wanted to be diplomatic. After reading the stats provided by the Frank Sinatra (it weighs 575 lbs.!), I asked a simple question.

Me: Bench looks beefy. How do the holdfasts work?

Frank Sinatra: Don’t know. Haven’t used the bench yet. Just finished it last weekend.

Suckier Workholding

It’s a simple note via email: You don’t need vises. No one needs vises. Take a look!

The bench in the photos is a 4x4x8 box made of plywood. Every foot or so is a vacuum port. They are on the benchtop. On the end of the box. On the front face. The bench is powered by two large compressors, which, through a venturi nozzle, provide the vacuum power.

Now there is no need for vises. Place your work on the vacuum port and it is immobilized. Cutting dovetails? No problem! The work is held immediately upright, ready for sawing! Planing? Put it on the benchtop and the vacuum ports hold it fast. No planing stops. No tail vises. No nothing.

I ask a question: How does it hold rough stock? Stuff that is fresh off the sawmill?

To this day, I still haven’t heard a reply.

Torsion or Tension?

Many times the Frank Sinatras come at me with their torsion box designs – “The T-Box Rules!”

So instead of a simple slab of wood, the T-box designer wants to make a benchtop from thin skins of plywood that cover a baffle system of thin components. This is a great way to make a lightweight tabletop that has a lot of visual presence. But a workbench top?

Me: How will you get holdfasts to hold in a torsion box?

Frank Sinatra: Those areas will be solid wood, surrounded by air.

Me. What about the dog holes?

Frank Sinatra: Same answer. Solid wood in the areas for the dogs.

Me: Don’t you want some mass? This benchtop weighs only 17 lbs.

Frank Sinatra: I’m going to fill all the cavities between the baffles with sand.

It’s Not a Bench. It’s the World

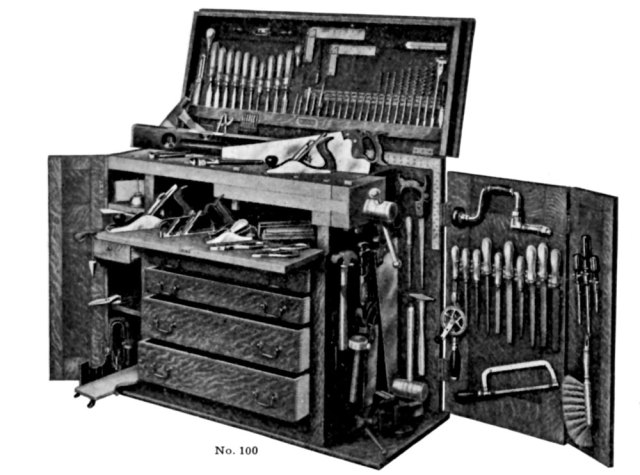

A common Frank Sinatra affliction is to add endless functionality to the bench. A table saw is integrated into the benchtop. A planer is in the base. There is tool storage galore. A fridge. A router table. And Bluetooth.

But does it work? Outside of your mind? Outside of a piece of paper?

— Christopher Schwarz, editor, Lost Art Press

Personal site: christophermschwarz.com

Next up: Workbench Personality No. 6: The Undecider